20th Century architecture: Is it the end of our 'concrete jungles'?

- Published

Birmingham - a city where 1960s concrete architecture is being rapidly replaced

Some of the 20th Century's best-known "concrete cities", such as Birmingham, Hull, Portsmouth and Coventry, are embarking on major regeneration work. But as the bulldozers move in, what is being lost?

Concrete was the building material beloved by councils as they embarked on post-World War Two development.

But it is fair to say many people were never quite as taken with grey skyscrapers and suspended walkways.

Now several of the cities defined by concrete - Birmingham, Coventry, Hull and Portsmouth - are undergoing multimillion-pound makeovers.

But what are they losing in their quest to be the "modern cities" of the 21st - rather than the 20th - Century?

Portsmouth

Owen Luder's Tricorn Centre was described by Prince Charles as a "mildewed lump of elephant droppings"

From the window of her office, Kathy Wadsworth, Portsmouth Council's strategic director of regeneration, can see a 1960s shopping centre and a block of flats.

"It's concrete, concrete, concrete," said Ms Wadsworth, who has been in her job for six years.

Now she and the council are in the process of "beautifying" Portsmouth - one of several heavily-bombed English cities with what some regard as an "unfortunate" post World War Two legacy.

"There was an old car park and shopping centre here called the Tricorn Centre which was voted one of the ugliest buildings in the UK - it was hideous," said Ms Wadsworth.

These outline proposals for Portsmouth's Northern Quarter could transform the area

The Tricorn, a concrete construction from the mid-60s which was described by Prince Charles as "a mildewed lump of elephant droppings", was demolished in 2004.

"I would have been leading the charge to knock it down," said Ms Wadsworth.

Nearly £2bn of investment is being pumped into Portsmouth over the next few years. Brutalism is out. Plate glass is in.

Portsmouth's Gunwharf Quays is one area of the city that has been so far regenerated

Where the Tricorn once stood, a £300m shopping and housing development called the Northern Quarter is springing up.

But in the rush to change Portsmouth's image, is something being lost along the way?

Owen Luder, the architect behind the Tricorn Centre, believes it is.

"There's a historical witch-hunt going on," he said.

"We are in danger of destroying the best of the '60s and early-'70s architecture under the assumption it was all bad. They are buildings of their time and if we destroy them, there won't be a record."

However, Ms Wadsworth is unrepentant.

"We have beautiful old buildings here that we wouldn't change a brick of," she said.

"So I can empathise with people who want to keep things. But I wouldn't let that stand in the way of redevelopment."

Birmingham

John Madin's 1974 library will be one of the casualties as Birmingham seeks to reinvent itself

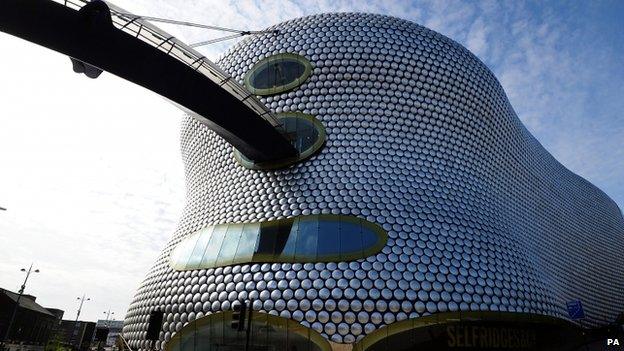

Birmingham's journey from "concrete jungle" to futuristic metropolis began more than a decade ago, with its radical reworking of landmarks such as the Bullring Shopping Centre.

It continues to this day, with the replacement of its central library and major transport redevelopments, such as the £650m work on New Street Station, due to be completed in 2015, and a new HS2 station.

Birmingham's New Street Station redevelopment is one of a number of multimillion-pound projects taking place in the city

An artist's impression shows New Street Station's future steel-clad exterior, which will replace the current concrete and pebbledash

Shopping and leisure quarters, such as Paradise Circus and Centenary Square are also being reworked.

Casualties include what many call the "old" Central Library, designed by architect John Madin, who died in 2012. And "old" is perhaps not an accurate description as the building only went up in 1974.

Birmingham's concrete legacy is a sign of its post-war confidence, according to some

John Glenday is the secretary of The Rubble Club - a society for bereaved architects who have seen their creations destroyed in their lifetimes.

"Architects are seeing their pride and joy reduced to rubble before their eyes," Mr Glenday said.

The Rubble Club - a group of architects who have seen their buildings demolished - says everyone has a different idea of what beauty is

"Everyone has a different idea of what beauty is. For some, it might be a thatched cottage but there are other aspects of beauty found in concrete, brutalist buildings.

"The Madin library is a concrete masterpiece and a striking landmark in Birmingham.

"The new library is a fantastic building. But it seems a shame to build one good building and lose another. There's a argument refurbishment might have been more sensible."

Buildings like Birmingham's "bubble wrap" Selfridges have become new landmarks of the city

English Heritage battled unsuccessfully to get Madin's library a Grade II listing.

"We believe many local people will be disappointed to see it lost," a spokesperson said.

"Birmingham was a real success story in the post-war world. It was challenging London and was a dominant player in the UK economy," said Mr Glenday.

"It should be celebrating and building on that legacy and I'm not sure demolishing the buildings from that period is the best way to do that."

Much of Birmingham's concrete architecture - such as the old Bull Ring shopping centre - dates from the 1960s, at a time, says The Rubble Club, when the city was challenging London

Some might argue there is a pleasing justice in seeing the buildings that replaced Birmingham's fondly-remembered Victorian architecture - such as JH Chamberlain's 1882 library - torn down themselves.

But Mr Glenday said: "Just because we made that mistake once doesn't mean we should make it again."

Coventry

Much of Coventry's city centre was rebuilt following World War Two

Coventry was the original concrete wonderland.

Rising out of the rubble of World War Two, where the Blitz and 1930s town planning had laid waste to its tangle of medieval lanes, the all-new Coventry was the brainchild of town planner Sir Donald Gibson.

"Gibson did some excellent work," said Colin Walker, vice chairman of civic group the Coventry Society.

Coventry's elephant-shaped leisure centre is one city landmark that could go, as the building has been deemed "past its sell-by date"

"Coventry at that time was a bomb site and anything was better than that. But I don't think Coventry works as well as it did 60 years ago."

He added the city's famously innovative ring road had created a kind of "rotten doughnut" in the city centre.

"Today most people prefer to shop in Solihull. It's very sad," he said.

The new city design was the brainchild of city architect Sir Donald Gibson

Take a walk around Coventry's precincts and plazas and you will come across a plaque celebrating Gibson, containing his famous quote: "If you cannot put up buildings of your own time, you might as well forget it."

Today, that philosophy could threaten Gibson's own vision for Coventry, as the city plans £900m of investment in its buildings and roads.

The council says the new proposals for the city centre are "logical and inviting"

"We want to make the city centre as logical and inviting as it can be," said David Cockcroft, assistant director for city centre development services.

"You have to get the retailers in and that means plate glass shop fronts and streets retailers recognise."

However, there are fears buildings of "superb character" could be lost in the rush to redevelop

Mr Walker fears the council's failure to employ city architects could leave it at the mercy of big corporations

But Mr Walker says councils' failure to employ architects has left town planning at the mercy of big corporations who do "what's most profitable for them".

Mr Walker says few councils employ the modern-day equivalent of Sir Donald Gibson, leaving them at the mercy of big commercial companies

He is concerned buildings of "superb character" - such as the elephant-shaped Fairfax Street leisure centre - could be lost in the changes.

"If it goes, it will be sad," he said, "but what will probably be more sad is what will replace it."

Hull

Hull is set to invest £25m in its city centre as part of its plans for its 2017 City of Culture celebrations

"The City of Culture? Hull?" was the sniffy reaction of some to the news it had been awarded the prestigious title.

"Everybody in Hull detected that feeling but I wonder how many of the people saying it had actually been to Hull," said artist and photographer Andrew Reid Wildman.

Some 20th Century buildings in Hull have been "sorely neglected" says Mr Reid Wildman, who fears for their future

Mr Reid Wildman is Hull born-and-bred and the city lies at the heart of his work.

"I'm very passionate about Hull's post-war architecture," he said.

"I grew up with it so it reminds me of my childhood. Hull was very badly bombed during the war and its 1940s city centre gives it a very special feel."

He has meticulously recorded what he sees as period masterpieces, now sorely neglected.

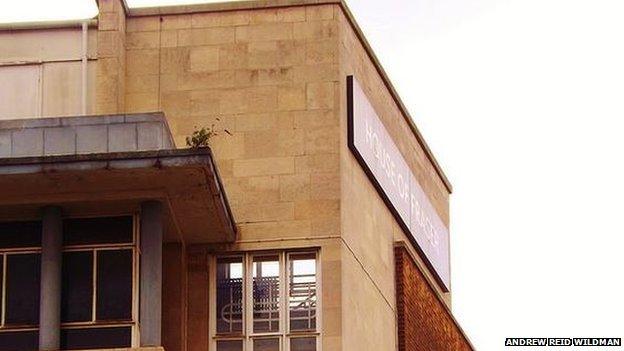

"The old Hammonds department store - now House of Fraser - is pure 1950s," he said.

"It has such an optimistic feeling. You can almost feel the energy of that time - the war was over and they were building something new."

Mr Reid Wildman says the House of Fraser - formerly Hammonds - is "pure 1950s"

Hull is set to invest £25m in a public realm programme as part of its 2017 city of culture preparations.

Mr Reid Wildman is concerned that could mean some post-war buildings are under threat.

"I hope Hull gets lots of nice new buildings, but on wasteland and other sites so it does not destroy what is left of the post-war stuff," he said.

The former Co-Op building with its mural of the fishing industry is one building Mr Reid Wildman fears could be under threat from developers

For many, the concrete facades of the '60s simply do not work in modern cities.

Stefan Kruczkowski, a senior lecturer in urban design at Nottingham Trent University, said: "One of the problems with brutalist architecture is that a lot of it was built with cars in mind and completely ignored pedestrians.

A sign of things to come? Sir Terry Farrell's Deep Aquarium in Hull

"Some of these buildings bear no relation to their surroundings.

"It's a risk to say, 'It's concrete, so pull it down'. But if it's a big, inward-looking beast, it can suck the life out of a city centre."

Allowing concrete buildings to decay and be demolished is like "airbrushing out a period of history" says urban planner Adrian Jones

But for Adrian Jones, a former planning director at Nottingham City Council who now writes about urban design, external, the term "concrete jungle" is part of the problem.

"It gets in the way of how we evaluate our towns and cities," he said.

"The danger to me of seeing everything from the '60s as a concrete monstrosity worthy of demolition is that it airbrushes out a whole period of history and architecture."

Mr Glenday of the Rubble Club agrees.

"Cities like Coventry and Hull wear their history on their sleeves," he said.

"If we start meddling in that, the sense of history starts to fade."

- Published27 February 2014

- Published14 December 2015

- Published19 December 2012