Liverpool Giants: Lord Derby and the Pals battalions

- Published

Edward George Villiers Stanley, the 17th Earl of Derby, at the BBC in 1931

The Liverpool Giants will not just be delighting crowds with their majestic grace - they will also be explaining how one man's vision changed the city forever when war broke out a century ago.

Edward George Villiers Stanley, the 17th Earl of Derby, was a lover of Liverpool and a patriotic man, so much so that Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, would one day call him the "king of Lancashire".

A former Grenadier Guard and Conservative MP, he served as Liverpool's Lord Mayor in 1911, was president of the city's chamber of commerce and chancellor of the university.

So when Lord Kitchener made an appeal for "the first 100,000" volunteers in August 1914, Lord Derby moved quickly to ensure the city was at the forefront of the World War One recruitment drive.

On 24 August, he met with Kitchener to ask if he could raise a battalion from the city's commercial class. Three days later, he called for men to serve in "a battalion of comrades" in the Liverpool newspapers.

He wrote: "It has been suggested to me that there are many men, such as clerks and others engaged in commercial business, who would be willing to enlist in a battalion of Lord Kitchener's new army if they felt assured they would be able to serve with their friends and not be put in a battalion with unknown men as their companions."

Lord Kitchener featured in a famous recruitment poster

Lord Derby was not the first to suggest such a battalion - by 27 August, London's 1,600-strong Stockbrokers' Battalion had been formed - but he was first to call them "Pals".

As he put it the next day, those signing up should form "a battalion of pals, a battalion in which friends from the same office fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of Liverpool".

On Monday 31 August, recruitment began at St George's Hall and, according to Tony Wainwright, the secretary of the Liverpool Pals Memorial Fund, showed "a snapshot of Liverpool as a centre of world trade".

"All the larger employers in the city had their own separate desk - these included the major shipping companies, such as White Star and Cunard, and other major players in Liverpool commerce including the Cotton Association, Corn Trade Association and the sugar trade."

By 10am, 1,000 men had signed up, enough to fill the battalion Lord Derby had promised Lord Kitchener, but many more were still willing.

The Liverpool Pals' war

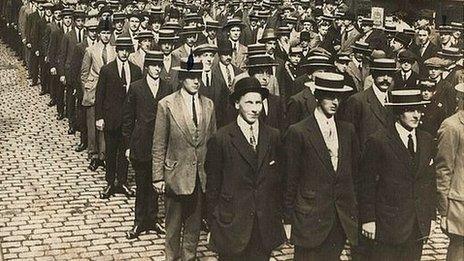

19th Battalion of the Liverpool Pals on a route march

Officially, the Pals were the 17th to 20th Service and 21st and 22nd Reserve Service Battalions The Kings Liverpool Regiment, and formed the 89th Brigade

On 20 December 1915, Reginald Rezin became the first Pal killed in action

On 1 July 1916, the Battle of the Somme - which saw the heaviest losses ever suffered by the British Army - began. The Pals lost 200 men on the first day, though their worst day came during a failed attack on the village of Guillemont on 30 July, where they lost almost 500 men

The battles of Arras and Passchendaele in 1917 also saw the Pals take heavy losses

In 1918, some of the battalions were disbanded, while others were sent to train American troops

On 8 November 1918, the 18th Battalion attacked German forces near Marbaux in the Pals' last engagement in the war. Thirteen men were killed

Within five days, the total had reached 3,000 and by October, there were enough from the city to form four Pals battalions in the Kings Liverpool Regiment.

Lord Derby's war effort continued after the battalions formed, as custom-built barracks to house three Liverpool battalions were built on his Knowsley estate.

Mr Wainwright says he became so highly thought of that King George V gave permission for the Pals to wear the Derby crest as their insignia - a move which saw Lord Derby produce silver cap badges for each of the men.

"Most of these were subsequently given to wives, girlfriends, sisters or mothers in the form of sweetheart broaches," Mr Wainwright adds.

Officers from the 19th Battalion of the Liverpool Pals in Knowsley Park

Professor Peter Simkins, author of Kitchener's Army, says while the idea of Pals battalions became popular, Lord Kitchener would only allow them if those who raised them paid for them, meaning they were "virtually private citizen armies".

He says that did not put people off and as a result, 215 of the service or reserve battalions which came into existence between August 1914 and June 1916 were raised by bodies other than the War Office - 38% of the total units formed.

The first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, however, dramatically changed the public mood.

Though the Liverpool Pals won one the day's few successes, taking the village of Montauban from the German army, they still lost 200 men and the majority of the other Pals battalions suffered catastrophic losses.

Whole units died together and for weeks after the initial assault, local newspapers would be filled with lists of dead, wounded and missing.

The huge casualties meant whole communities and workplaces were changed forever - by the end of the war, some 2,800 Liverpool Pals had been killed.

Lord Kitchener and the Pals

In August 1914, Lord Kitchener issued his first call to arms for 100,000 volunteers, aged between 19 and 30, at least 1.6m (5ft 3ins) tall and with a chest size greater than 86cm (34ins)

General Henry Rawlinson initially suggested that men would be more willing to join up if they could serve with people they already knew. Lord Derby was the first to test the idea in Liverpool

Liverpool's success prompted other towns to form units, with civic pride and community spirit driving a competition to raise the highest numbers

Tyneside raised eight battalions and two more were raised in Newcastle. Manchester raised seven battalions, Salford and Hull four, and Birmingham, Bradford, Edinburgh and Glasgow each raised three

Battalions such as the Hull Commercials shared an occupation. Others, like the Glasgow Tramways Battalion, shared an employer, while the Tyneside Irish had a common background.

As the death count rose, so the number of volunteers declined, but the War Office and Lord Derby had already put in place plans to make sure there were still men available to serve.

In 1915, Lord Derby gave his name to a scheme which saw every man under 41 asked either to join up at once or to agree to serve when summoned.

Under the scheme, men were divided by age and marital status, with single men aged 19 called up first. But it failed to answer the need for more soldiers, and full conscription was finally introduced in January 1916.

Despite the huge death toll, Lord Derby's popularity remained and he went on to become Secretary of State for War and later the Ambassador to France.

A book of condolence opened after his death in 1948 drew 70,000 signatures - a testament to a man who loved his country and in particular, the city that lay on the edge of his estate.

BBC News Online will be following the giants through Liverpool with live text coverage, pictures and video of events. For more details, visit the BBC's dedicated Liverpool Giants page.

- Published6 June 2014

- Published17 April 2014

- Published31 October 2013

- Published29 March 2011