World War One: The British hero who did not shoot Hitler

- Published

In 1938, Adolf Hitler himself is said to have told British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain that Pte Henry Tandey had spared his life 20 years before

Henry Tandey became the most decorated private soldier in World War One. His bravery though, would be eclipsed in the run up to World War Two by allegations he had spared Adolf Hitler's life, in 1918. But, is the story accurate?

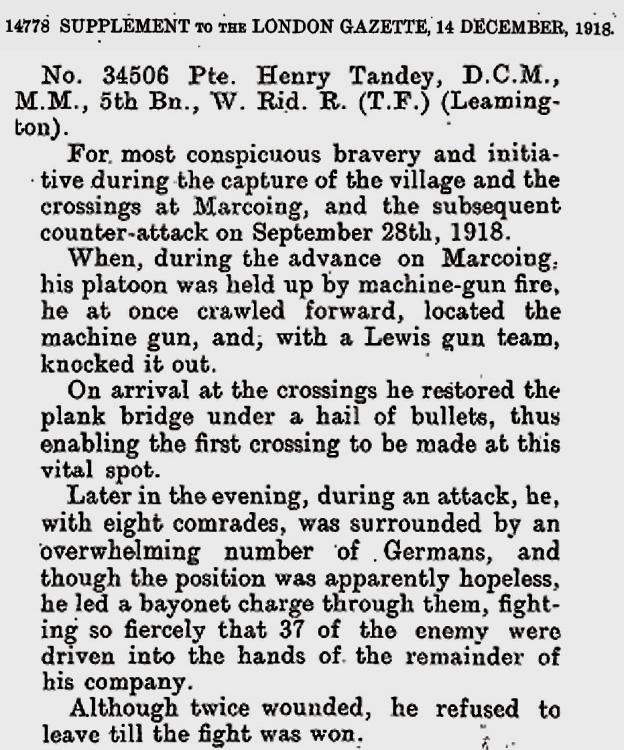

The two events were separated by 20 years. On 28 September 1918, Pte Tandey earned the Victoria Cross "for most conspicuous bravery and initiative" at the fifth Battle of Ypres.

Twenty years later, Hitler himself is said to have planted the seeds of the legend during a visit to the Fuhrer by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, in his doomed attempt to secure "peace for our time".

He apparently seized on the fact that along with many of his fellow soldiers, Pte Tandey had tempered justice with mercy, refusing to kill unarmed, injured men in cold blood. The leader of the Third Reich claimed he was one of those spared.

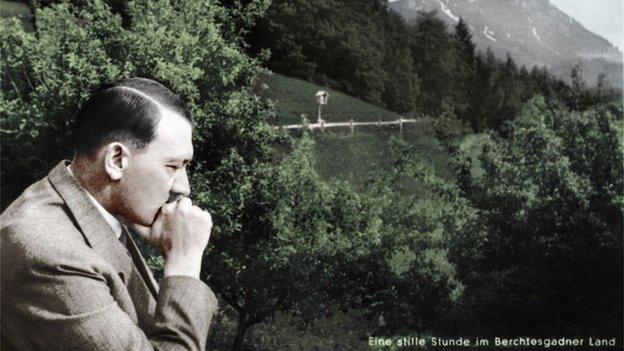

At his Bavarian retreat the Berghof, Chamberlain noticed a picture on the wall of Hitler's study, depicting a scene from a battle at Menin crossroads in 1914. The soldier in the foreground was apparently Pte Tandey, carrying a fellow soldier to safety.

Hitler told Chamberlain the soldier had pointed a gun at him but spared him.

"That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again," Hitler is alleged to have said.

"Providence saved me from such devilish accurate fire as those English boys were aiming at us."

The museum of the Green Howards - Pte Tandey's regiment, which commissioned the painting in 1923 from Italian war artist Fortunino Matania - confirmed a copy was hanging at Hitler's retreat.

.jpg)

The story created compelling headlines

The museum has a letter from Hitler's adjutant, Capt Fritz Weidemann, thanking them: "The Fuehrer is naturally very interested in things connected with his own war experiences. He was obviously moved when I showed him the picture."

The painting's route to Hitler's wall was fairly convoluted, centring on one of his staff, a Dr Otto Schwend, who had received a postcard of the painting from a British soldier whom he had befriended in WW1.

Hitler owned a copy of Fortunino Matania's painting of a post-battle scene at Menin crossroads

Hitler had apparently claimed to recognise in it a soldier he met in 1918, but the painting depicts a battle that actually took place in 1914.

Dr David Johnson, Pte Tandey's biographer, throws more doubt on the story.

Pte Tandey was awarded the Military Medal, the Distinguished Conduct Medal, and the Victoria Cross. He was also mentioned five times in despatches

He pointed out that even if the date were accurate it would have been unlikely for Pte Tandey to have been recognisable from the painting. He had been injured during the 1918 battle, and in contrast to the painting, would have been "extremely dishevelled and covered in mud and blood".

Perhaps even more compellingly, Dr Johnson argues there was no way Pte Tandey and L/Cpl Hitler could have crossed paths.

On 17 September, Hitler's unit had been moved about 50 miles (80km) north of Pte Tandey's, which was in Marcoing, near Cambrai in northern France.

Menin Road in the aftermath of battle. Fortunino Matania's painting depicts Pte Tandey at Menin crossroads, where a first-aid station was based

The meeting of the men was supposed to have happened on 28 September 1918, but papers at the Bavarian State Archive show Hitler had been on leave between 25 September and 27 September.

"This means that Hitler was either on leave or returning from leave at the time or with his regiment 50 miles north of Marcoing," Dr Johnson said.

He also said it was not likely that Hitler had been simply confused.

The Matania painting was seen by Chamberlain when he visited Hitler's Bavarian house in 1938

"It's likely he chose that date because he knew Tandey had become one of the most decorated soldiers in the war," said Dr Johnson.

"If he was going to have his life spared by a British soldier, who better than a famous war hero who had won a Victoria Cross, Military Medal and a Distinguished Conduct Medal in a matter of weeks?

"With his god-like self-perception, the story added to his own myth - that he had been spared for something greater, that he was somehow "chosen". His story embellished his reputation nicely."

It was another detail that also set alarm bells ringing, Dr Johnson said.

No telephone

On returning to Britain, Mr Chamberlain is alleged to have phoned Pte Tandey to pass on details of the exchange he had with Hitler.

He was out at the time, so a nephew apparently took the call.

Dr Johnson is highly sceptical the call was made, not least because Mr Chamberlain was a very busy man.

"I can't see him spending time tracking down and telephoning a Private," he said.

"He also sent long and detailed letters to his sisters and kept diaries. Nowhere in his papers was the Tandey affair mentioned."

British Telecom archives add more doubt - Pte Tandey did not have a telephone.

But the story has persisted, having probably first come to light at a regimental event in 1938 where, Dr Johnson said, Pte Tandey was told by an officer who had heard it from Mr Chamberlain.

"We don't know whether Tandey was taken to one side and told privately - or whether it was a jocular part of an after-dinner speech, or something like that," he said.

Pte Tandey himself was noncommittal about it. He acknowledged he had spared soldiers on 28 September, and was initially prepared to entertain the idea - but always made a point of saying he needed more information to confirm it.

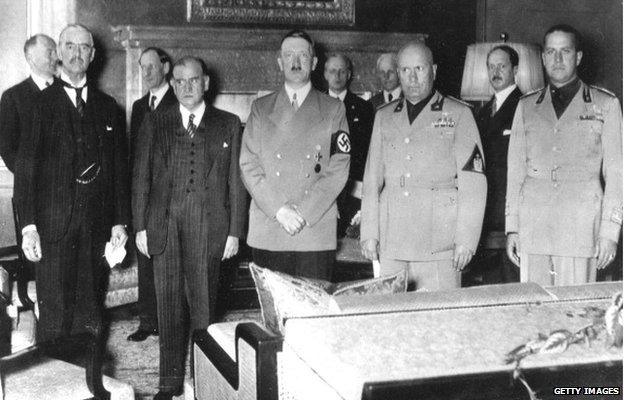

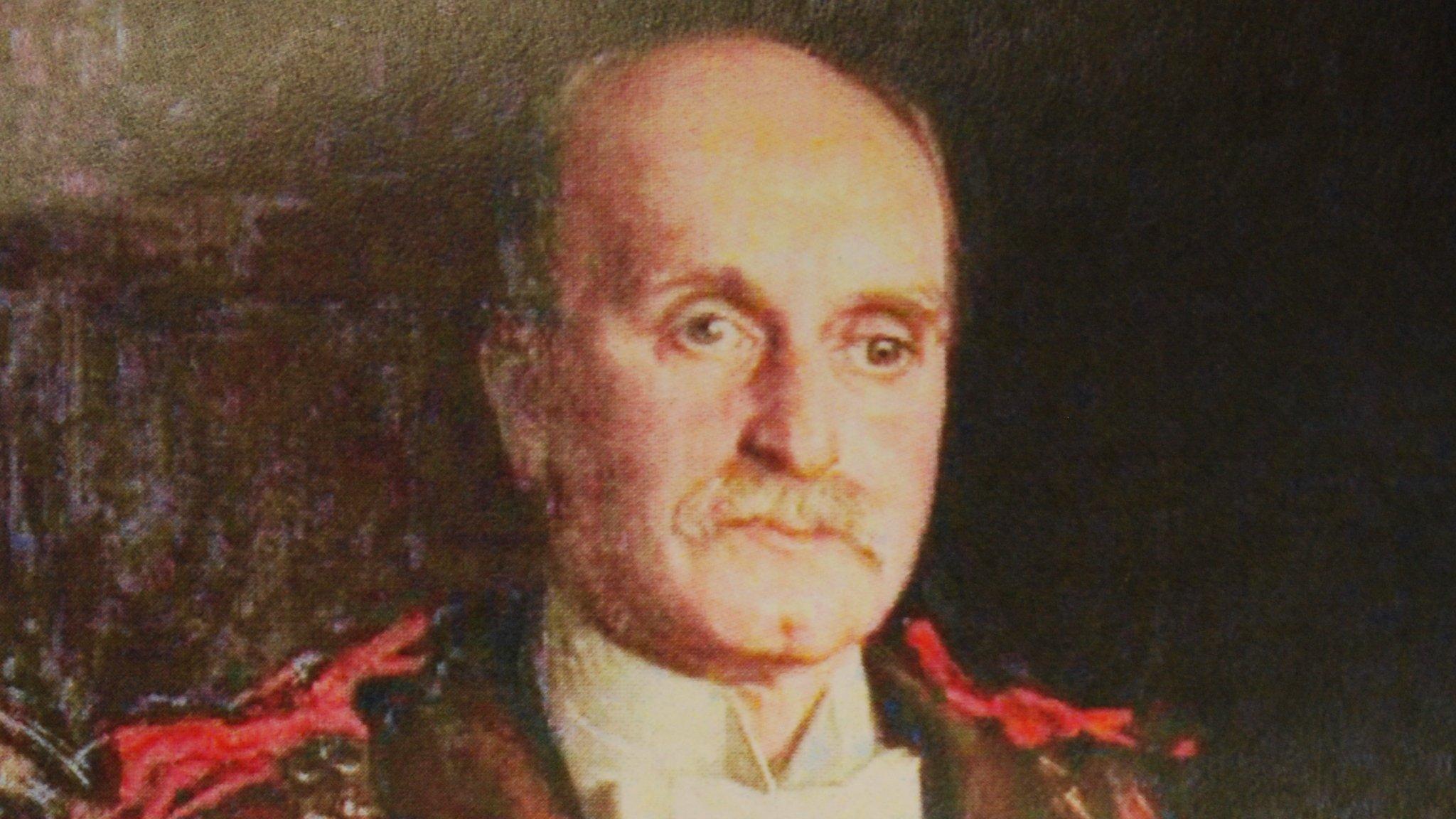

Preparing to sign the 1938 Munich Agreement: (l-r) Chamberlain; French Prime Minister Daladier; Hitler; Mussolini and Italian Foreign Minister Count Ciano

He was quoted in an August 1939 edition of the Coventry Herald as saying: "According to them, I've met Adolf Hitler.

"Maybe they're right but I can't remember him."

But a year later, he appeared to be more certain, when a journalist approached him outside his bombed Coventry home, asking him about his alleged encounter with Hitler.

"If only I had known what he would turn out to be," Pte Tandey is quoted as saying.

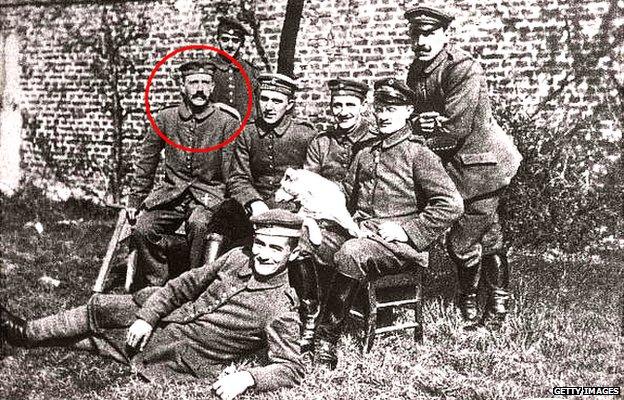

Adolf Hitler would look considerably different 20 years later

"When I saw all the people and women and children he had killed and wounded I was sorry to God I let him go."

The newspapers seemed to say it all:

"Nothing Henry did that night could ease his sickening sense of guilt."

"It was a stigma that Tandey lived with until his death"

"He could have stopped this. He could have changed the course of history"

However, there is no evidence, not even anecdotal, he was either hounded or avoided after the claims.

'Extremely dishevelled'

"It must be remembered that this was a low point for the country and for Coventry, and Henry can be excused for feeling a little sorry for himself and emotional after the sights he had witnessed," Dr Johnson said.

"We must not forget that in 1918, no-one knew who Hitler was. Why would Henry remember and regret that specific encounter, especially when Hitler would also have been extremely dishevelled and covered in mud and blood, not looking like he did 20 years later.

"It might be equally true that the journalist concerned took Henry's comments out of context, which might go some way to explaining his distrust of the press."

Pte Tandey's bravery was documented in the London Gazette

Wartime mysteries - was the Chilwell explosion accident or sabotage? And, was an associate of Churchill guilty of spying, as his accusers insisted?

- Published25 February 2014

- Published5 July 2012