Scottish referendum: What does it mean for England?

- Published

Fishermen along the Tweed - the river that runs through the English borders - question what the Scottish vote means for them

Across Northern Britain, Scots are waking up to find their country has voted to remain part of the United Kingdom. But how will their decision affect England?

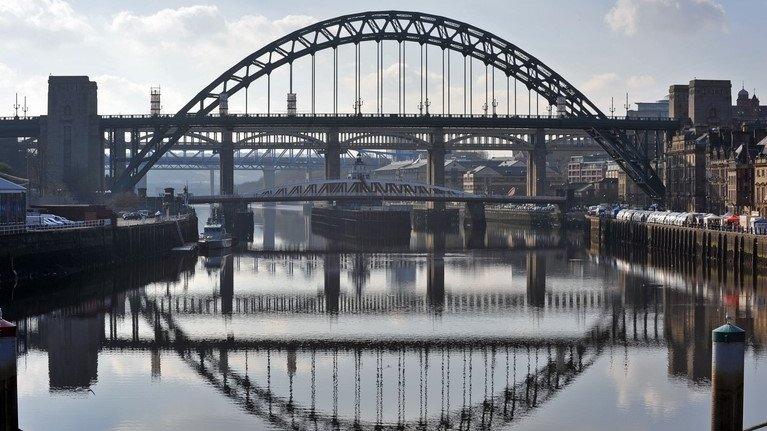

The River Tweed has twisted along England's northern border for centuries.

Along the meadows and gardens that slope down to meet it, you will see anglers patiently hoping to catch the trout and salmon for which the river is famous.

But this morning, those who live along the river are waking to find this unchanging part of the world has changed irrevocably.

For despite the success of the "No" campaign in Scotland, it will mean big changes - changes that are not altogether welcome on the English side of the border.

Northumberland

Residents of Berwick say they are envious of Scotland's better public transport links

Among Northumbrian anglers, there is confusion about what increased powers for Scotland could mean.

Dave Cowan, from Tweedmouth, fishes on the river once a month.

"It's very peaceful - you can lose hours and hours here," he said.

He is concerned about how the Scottish government's plans to change salmon fishing might affect English anglers.

"There are a lot of things that are unclear at the moment. It could make life a little bit more difficult for us," he said.

People in Berwick feel they are a "very low priority" compared to those who live two miles away in Scotland

Continue into Berwick-upon-Tweed, the English town with a Scottish league football team, and there is a feeling of nervousness among residents.

"We feel we are going to get the worst of both worlds," said Derek Sharman, a tour guide.

"UK politicians have thrown everything at Scotland and those of us across the border feel we are a very low priority."

Derek Sharman says the Scottish government seems to understand rural communities better

Public transport is, in Mr Sharman's view, a case in point.

"If you come to Berwick on a Sunday, public transport is almost non-existent, whereas in Scotland it's almost as good as it is on a weekday," he said.

"The Scottish government seems to have a better understanding that rural communities need better transport."

Ten years ago, residents of the North East voted against a regional assembly

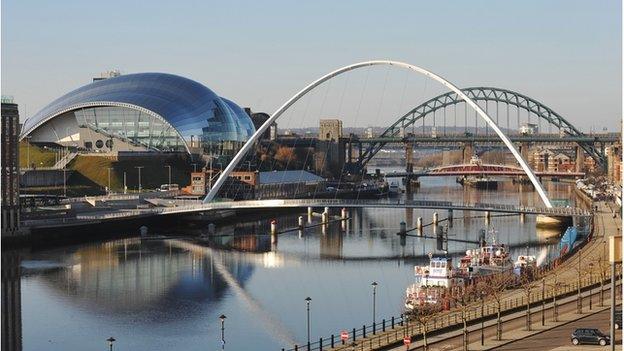

Travel further down Northumberland, towards Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and the mood seems to change.

In June, former Labour MP Hilton Dawson set up a new political party - The North East Party - which, he says, will campaign for "everything Scotland has".

"The huge lesson of Scotland is that these issues can inspire people who have never been involved in politics before," he said.

"We are not going for independence - just devolution for the North East, which will mean the big issues are decided here, rather than by going as supplicants to Westminster."

Former Labour MP Hilton Dawson has set up a North East Party to campaign for regional devolution

Mr Dawson admits the region has "been here before", referring to the referendum on regional assemblies in 2004, external, which met with a resounding "no" vote.

"The vote failed 10 years ago because the offer wasn't strong enough," he said. "This time, the demand for devolution is overwhelming - we've seen how successful it has been in Scotland and Wales."

Residents who live on the English side of the Tweed say a government in Newcastle would feel as remote as one in London

However, Mr Sharman feels increased regionalisation is not the answer.

"In Berwick, a regional government based in Newcastle would feel just as remote as a central government based in London," he said.

Manchester

Greater Manchester is home to England's first statutory combined authority

One city where the regional devolution campaign seems ready for lift-off is Manchester.

The city has always revelled in self-definition, whether through its red-brick Victorian Gothic architecture or through its independent music scene of the 1980s and 1990s.

On Tuesday, the region was the subject of a report by centre-right think tank ResPublica which said it should be given income-tax raising powers and complete control of spending within five years - a plan termed "Devo-Manc".

The global prominence of Manchester's football teams has helped generate confidence in the city, say experts

Greater Manchester is already home to England's first statutory combined authority, which oversees transport and regeneration schemes.

"A whole host of things - from the development of Media City to Manchester City's new prominence - have come together to put Manchester on the global map," said Colin Talbot, professor of government at the University of Manchester.

"I think Greater Manchester is probably the most advanced of all the regions in terms of being ready for devolution."

Campaigners want Greater Manchester to have greater control of its money

Jonathan Schofield, who edits the magazine Manchester Confidential, agrees.

"Devolution for Manchester is an inevitable consequence of the Scottish debate," he said.

"Politicians have been a bit panicky and have offered Scotland a lot of things. You'll get English regions saying, 'Why aren't we getting some of this?'"

Mr Schofield says he cannot imagine Westminster allowing Greater Manchester its own tax-raising powers, but he can see the area getting greater control of local spending.

The BBC development at Media City UK has helped put Greater Manchester on the map, according to Professor Colin Talbot

"Why not use Manchester as a test-bed?" he said. "You look at European cities, which have far more freedom, and everything is better from parks to litter picking because they can control their budgets.

"It's good for the country not to have this idiotic London bubble running everything."

Yorkshire

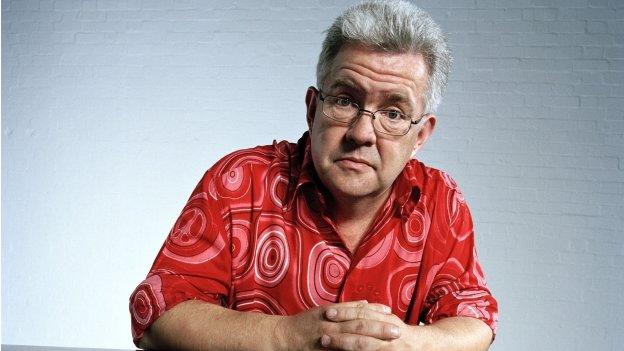

Poet Ian McMillan believes his native Yorkshire - which has a similar population size to Scotland - should get more power

If Manchester were to get greater powers, there is a fair chance the people across the Pennines would wish to do likewise.

"Yorkshire has always seen itself as superior to everywhere else, so there is a bit of that in it," said the bard of Barnsley, poet Ian McMillan. "But there is a serious side to the debate too.

"Yorkshire and Humberside have almost as many people as Scotland and I think there will be a call for us to get more power."

Yorkshire is more than ready for devolution, Mr McMillan says

Mr McMillan warns devolution is not a "panacea to save us from all ills".

But he believes there will be a "very short window" after the Scottish vote, when those who want regional devolution will be able to make their voices heard.

"Everybody's talking about it and we're definitely ready," he said. "We have our own flag, external. We have our own national dish - the Yorkshire pudding. We need to strike while the iron's hot."

Birmingham

Birmingham and its surroundings are less enthusiastic about the idea of regional governance

One region where devolution is not being welcomed with open arms is the West Midlands.

In May, Birmingham and its surroundings saw considerable debate around the idea of rebranding parts of the West Midlands as "Greater Birmingham", with many towns and cities fearing such a concept would leave them overshadowed.

Peter Lyons said he could not imagine Birmingham surviving on its own

Would the same fears persist over a regional parliament - perhaps one centred in Birmingham?

"I can't understand how it would work," said Peter Lyons, a butcher from Knowle. "I can understand how everyone thinks London gets the better deal but I can't see how Birmingham could survive on its own."

"There's much less of a feeling of wanting to go it alone in the Midlands," added Jude Tree, who lives near Solihull.

Politics lecturer David Craik says many people in the region are happy with the status quo.

"Birmingham wants to assert itself as a centre of business and industry but it doesn't have a strong desire to break from the Westminster system," he said.

England

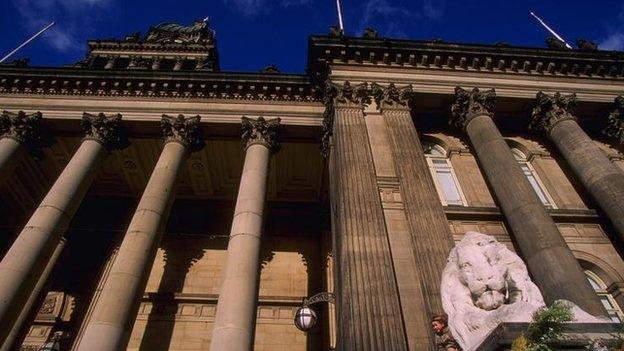

The Victorian architecture of Birmingham and Manchester suggests the power of both cities before World War One

Of course, it would not be the first time the English regions have enjoyed some autonomy.

Between 1870 and 1914, Linda Colley, professor of history at the University of Princeton, says local governments raised about half of all the money they spent through local taxation.

Today, she says, central government provides more than 80% of local government funds and dictates how the money is used.

"It's worth considering how much of the current disquiet and disaffection in parts of the UK is caused by the overmighty reach of London which needed to centralise power in order to fight two world wars and has not been all that willing since to surrender power back," she said.

She suggests one idea could be to create an English parliament - located somewhere in northern England - to help lessen the north-south divide.

But for the regionalists, an English parliament would not satisfy their demands.

"The English identity has largely been subsumed into the British identity," said Professor Talbot. "People's experience is of their local areas. They don't necessarily identify much broader than that."

- Published15 September 2014

- Published17 September 2014

- Published15 September 2014

- Published6 September 2014