World War One: Mysterious deaths of the English flying aces

- Published

The lives - and deaths - of aces McCudden, Mannock and Ball have become part of aviation legend

The three biggest-hitting British air aces of World War One rose from quiet backgrounds to become national heroes - but their deaths have still not been fully explained.

In 1914, the sky was a new battlefield, with startling contrasts.

On one hand it was daring and exotic, but with flimsy planes and no parachutes, it was also infamously dangerous. At one point the life expectancy of a new pilot sank as low as 17 days.

But three men, for a time, beat the odds and rose to national renown, before succumbing to extraordinary twists of fate.

Edward Mannock was probably the most enigmatic of the three. His birthplace is uncertain, his final tally hotly disputed, his grave unmarked.

Born in 1887, claims have been lodged for Aldershot, Brighton and Ballincollig, but when his soldier father deserted the family in 1909 they were in Canterbury, Kent.

Looking for work he moved to Wellingborough, Northamptonshire and he returned there on leave during the war.

In 1916, Mannock joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1916, with his Irish mother earning him the nicknames Mick and Pat.

Air fighting in World War One often happened at close quarters, conjuring an image of jousting knights

Joshua Levine, author of Fighter Heroes of WWI, says: "Mannock is one of the most fascinating personalities to come out of World War One, he is so unlikely as an ace.

"He was older, working class, a strongly minded socialist and supporter of Irish home rule.

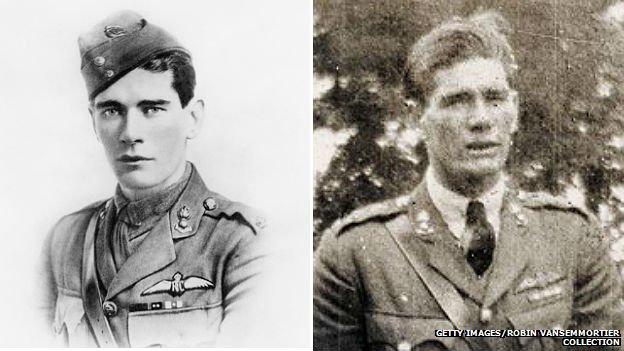

Mannock near the beginning and end of his flying career

"He wasn't a natural flyer, he was scared and admitted it - almost unthinkable to most pilots - which led to allegations he was 'yellow', a coward.

Violent death constantly stalked pilots both in the form of accidents and in battle

"What he then did was remarkable. He rationally sat down and worked out a series of rules of how to fight.

"Crucially this could be taught and as his successes grew, he became more popular, even idolised."

On 26 July 1918 though, he broke one of his own rules and circled a plane he had shot down. Within seconds his own plane was struck by ground fire, burst into flames and crashed.

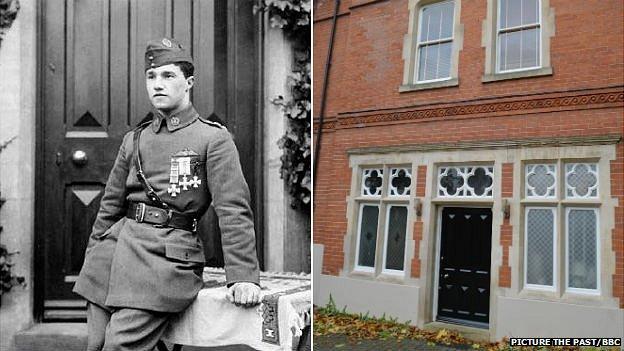

Mannock's home in Wellingborough has a memorial plaque but his final resting place is disputed

"He had become increasingly bleak in his outlook and maybe there was an element of if he was going to die then he would choose how," Mr Levine says.

"He didn't forget his rules but this time chose to ignore them, to look fate in the eye and see what happened."

The Germans reported finding and burying Mannock's body but the spot could not be traced after the war. His names stands on the memorial for missing airmen.

However, recent research has shown a body of a pilot was exhumed nearby but placed in an official grave as an unknown.

It is a double irony that the methodical pilot was killed by rashness and his celebrity status did not save him from an anonymous grave.

James MuCudden was obsessed with the mechanics of his aircraft and the tactics of air warfare

James McCudden's career mirrored Mannocks, in that he rose from a humble military family, in Gillingham, Kent, to inspire the country.

Author and historian Alex Revell says: "McCudden's attitude to flying was the same to everything he did. His rule was: 'If a thing's worth doing, it's worth doing well'.

"To rise through the ranks from air mechanic to major in under five years was remarkable in those very class conscious days."

Three aces

•Albert Ball VC: Aged 21; 44 official victories

•Edward Mannock VC: Aged 31; 61 official victories

•James McCudden VC: Aged 23; 57 official victories

He scored rapidly and his successes led the government to name its top fighters. At home on leave he dismissed the attention as "bosh".

Flying back to France on 9 July 1918 , McCudden landed his brand new plane at small aerodrome called Auxi-le-Chateau to check his location. On leaving, his plane struggled, swerved and crashed into a wood, leaving him fatally injured.

Several witnesses said he had been trying to perform a stunt at the time. Others said they heard his engine misfiring.

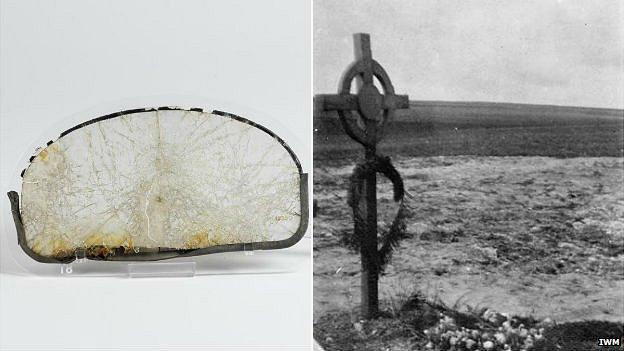

The windscreen of McCudden's plane gives an indication of the force of the crash that killed him

The official report, routine after every crash, was either not carried out or quickly went missing.

Mr Revell interviewed Captain Herbert Charles, the RAF's accident investigator, who inspected the wreckage.

Mr Revell said: "He gave me the impression that he considered that there had been a cover up, but was reluctant to go on record in saying so.

"He found an obsolete air filter had been fitted which would have led to the engine failing during a steep, climbing turn.

"Personally, I think Charles believed it was a manufacturing fault by the Royal Aircraft Factory, which built the SE5a McCudden was flying."

England's leading ace had been killed not by the enemy but perhaps by a clumsy mistake in a home front factory.

Albert Ball was raised in the traditions of national pride and public school

Unlike the others, Albert Ball was neither steeped in military life nor dogged by poverty.

Pilot and aviation historian Paul Davies said: "Ball was the first British pilot to become a celebrity, he was taken to the heart of the nation which needed good news, helped by his boyish looks and patriotic attitude."

Born in 1896, his well-off businessman father made sure he attended a good public school in his native Nottingham.

Mr Davies says: "Ball grew up believing he had to put his country first, he had 'Britain' running through him like letters in a stick of rock.

"Desperate to live up to his father's expectations and his own sense of duty, the war was in some ways an ideal opportunity."

Ball's visits to his home in Nottingham caused a media frenzy, and the doorway where he posed survives

He arrived in France in February 1916 and immediately began to gain victories. While lacking the methodical wisdom of Mannock and McCudden, he had his own strengths.

"He was a mix of extraordinary bravery and boyish naivety. He became known for charging straight into enemy formations yet was embarrassed by public attention.

"He disliked the act of killing but felt it was a necessary thing to do to defend his country," says Mr Davies.

Ball's crash site is still marked by the original memorial

On 7 May 1917, near Douai, Ball became involved in swirling dogfight. Ball pursued an opponent into low cloud but moments later his plane reappeared, upside down. It crashed behind German lines.

Claims Ball had been shot down were disproved as his plane and body suffered no bullet damage. The nation was shocked and confused.

Mr Davies says his air experience might give him an insight into what happened: "The dogfight came at the end of the day and everyone was running low on fuel, perhaps this made his engine fail.

"But also by this stage of the war he was far more disillusioned, he had seen a lot of friends die. He was physically and mentally weary.

"It could be this meant he became more disorientated in the cloud, rolled his plane and reacted more slowly when he came out of it."

He was buried with some pomp by the Germans and his father paid for a memorial at the crash site.

Mr Levine says: "The British authorities didn't want any of them to be turned into heroes but there was an immense public appetite to put a human face on what was essentially a faceless war."

- Published17 June 2014