UK: What Next? What will the North West look like under devolution?

- Published

There is concern in some parts of the North West that the devolution revolution will benefit Greater Manchester over other areas

Back in June, George Osborne stood in the Power Hall of Manchester's Museum of Science and Industry and outlined his plan for re-energising the North West.

It was a symbolic setting since the gallery contained steam locomotives which once ran between Liverpool and Manchester.

The chancellcor and MP for the Cheshire constituency of Tatton spoke of his vision for a "Northern Powerhouse", working cohesively to generate wealth not only in those big cities but across the North, from Liverpool in the west to Hull in the east.

George Osborne: "It is the first time we've ever had a city-wide mayor outside London"

The view from Manchester

By BBC Radio Manchester political reporter Kevin Fitzpatrick

Council leaders in Greater Manchester have long argued against a directly elected mayor for the region but the deal on the table was too good to turn down.

One leader was "amazed" at the powers the government was prepared to give away. Control of around £2bn of extra budgets and power to decide what happens with transport, housing, planning and policing proved a carrot enticing enough for them to sign an agreement with George Osborne, although some leaders are still urging caution and describing the deal merely as a "move to the next stage".

Crucially, to ease fears of an all-powerful individual ruling the roost, this directly elected mayor will sit alongside, and not above, the other leaders. They'll need the support of two thirds of them to push their policies through. It appears that Greater Manchester is to get the powers it wants without the kind of mayor it didn't want.

Historically though, implementing this strategy has been more like driving a supertanker than a locomotive. For decades, Whitehall has sucked power away from local government. Ministers and civil servants believed they could spend taxpayers' money more efficiently and prudently than local politicians could.

But policy is changing rapidly among all of the political parties - one Greater Manchester MP even described it to me as being like an arms race.

Nowhere has benefited more than Greater Manchester. Mr Osborne's announcement on Monday is hugely significant, offering the 10 boroughs of Greater Manchester direct control over billions of pounds of public spending. At this point, though, it is also worth remembering how much money local government has lost since 2010.

Power to the North West

79%

of people living in the North West agreed politicians in Westminster do not understand what is best for the rest of the UK

-

74% of people in the region agreed that too much of the country's resources were spent on London

-

50% of people in the North West disagreed with the idea of an English parliament for English-only constituencies

But while the pot may be smaller, they will at least be allowed to decide for themselves how best to spend money on public transport, increasing people's skills, work programmes and housing. It essentially trusts local politicians to make better decisions than Whitehall.

This plan has not emerged from nowhere. For years Greater Manchester has been proving its ability and maturity. The 10 leaders have put political and local rivalry aside, at least in public, and developed the city region under the "Manchester" brand. And Manchester City Council has benefited from stable political and administrative leadership under its leader Sir Richard Leese and chief executive Sir Howard Bernstein.

But that will no longer be enough. Because the Combined Authority is now getting greater responsibility, the government wants it to be more accountable to voters. That means there will be a directly elected mayor for Greater Manchester, probably from 2017. The 10 leaders are not so keen on that idea, and indeed a mayor for the city of Manchester was rejected by voters in a 2012 referendum. But it is simply not up for debate.

The view from Liverpool

By BBC Radio Merseyside political reporter Claire Hamilton

The idea of regional devolution for the North West is often met with a lukewarm response from Merseysiders - the belief being we would end up playing second fiddle to Manchester.

It's no secret Liverpool's mayor believes in drawing down as many powers as possible for the city region. He'd like to be able to raise and spend taxes locally, and drive the economy from Dale Street rather than wait for Westminster to apportion hand-outs.

Merseyside's political leaders struggled to establish a Combined Authority earlier this year, raising some questions about how such a plan would work.

Although Manchester is leading the way nationally, it's not the only game in town. The previous Labour government championed regional policy - the North West as a whole. But plans for a regional assembly were scrapped after voters rejected them in the North East.

By the time Gordon Brown was prime minister, the government was already favouring smaller city regions and then the coalition government scrapped the Regional Development Agency. It created Local Enterprise Partnerships, which are focused on smaller areas but have much less money. And ministers have signed city deals, including with Liverpool and Preston, which are designed to strengthen local economies in the longer term.

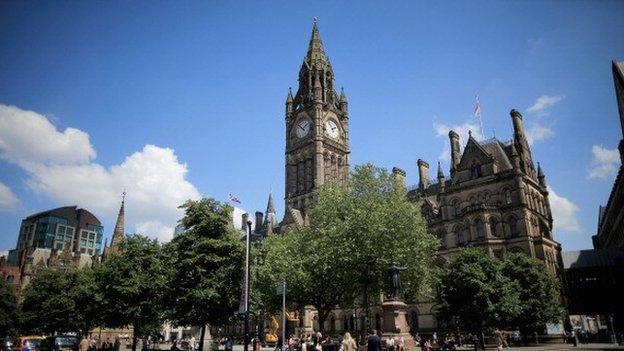

Devolved powers will allow Greater Manchester to decide how best to spend money on public transport, work programmes and housing

Liverpool's city deal was probably made easier because it had a mayor. In 2012, the Labour leader of Liverpool City Council Joe Anderson avoided a local referendum, changed the system and became mayor. The government liked that.

Earlier this year, the six neighbouring councils created the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. It got off to a poor start, however, with infighting over who should lead it. Some of the councils were afraid of being dominated by Liverpool, and Wirral's leader Phil Davies was elected chairman.

So far, Mr Anderson has been unable to persuade his colleagues to agree to an elected mayor for the wider city region. But it's possible they may change their minds when they see how Greater Manchester has benefited.

The personality issues within the Liverpool Combined Authority have not put neighbours off. West Lancashire Council has applied for associate membership. It clearly believes it has more to gain, in terms of transport and economically, by aligning with Merseyside.

The view from the Red Rose county

By BBC Radio Lancashire political reporter Chris Rider

Who will really benefit from this devolution revolution? Is it going to be the powerhouses in the form of Manchester and Merseyside?

If that is the case does this mean Lancashire County Council and borough councils across Lancashire will be left behind?

There is a cautionary tale to councils wanting more powers. Rewind the clock to 1999, a time when there was a North West Regional Assembly. It was set up to oversee the Regional Development Agency, which dealt with public spending but was fairly anonymous and eventually abolished in 2008.

We will wait to see how things work out. There is debate about whether people want more devolution in the first place and whether the outcome will be fair across all parts of the North West.

The district council remains part of Lancashire County Council. Lancashire does sometimes struggle to act as a cohesive whole - it was one of the last places to agree to a Local Enterprise Partnership, partly because East Lancashire sees its strategic interests differently from the rest of the county.

There's a similar challenge in Cheshire. The county council was abolished in 2009 and replaced by two large unitary authorities.

The leader of Cheshire East has already suggested they should unite, something which has been rejected by Cheshire West and Chester Council as irrelevant.

And I'm told Warrington Council, a very prosperous town, might ultimately choose to join either Manchester or Liverpool city regions instead.

That reflects a serious question about how other places respond when government policy appears to be very directly geared towards supporting the cities.

Click here to watch our North West devolution debate via the BBC iPlayer

- Published3 November 2014

- Published3 November 2014

- Published3 November 2014

- Published22 October 2014

- Published4 May 2012