Midlands marginal seats could swing 2015 election

- Published

- comments

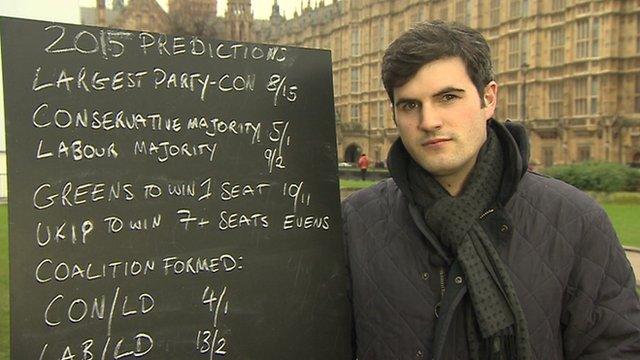

2015 could be a turbulent year for the main political parties

The onset of a new year in politics usually prompts a flurry of more or less confident predictions about what the coming 12 months have in store, especially when a general election is involved.

This time though, the consensus is that all we know is that we don't know.

Of all the nine general elections I have been involved in, this is by far the most unpredictable.

So it was more in hope than expectation that I set out in search of pointers to the likely wind direction on polling day.

And where better to start than the spire of the parish church of St Peter and St Paul at Coleshill in Warwickshire?

As "weather vane" constituencies go, this is as politically edgy as it gets.

Smallest majority

Coleshill is one of the main population centres in the constituency of Warwickshire North, where, at the last election, Conservative Dan Byles defeated former Labour minister Mike O'Brien by just 54 votes.

That's the second smallest parliamentary majority anywhere in Britain and the smallest here in our region's traditionally volatile electoral micro-climate.

Mr Byles has become best-known for his outspoken opposition to his government's plans to drive high-speed rail through the constituency.

Indeed Coleshill is acutely aware of its neighbouring transport infrastructure, bordered as it is by the M42, Birmingham Airport and the existing West Coast Mainline. But Mr Byles has decided to stand down at the election and Labour has identified Warwickshire North as its number one target here.

And that generally has been the political narrative we have become used to in our part of the country: A predominantly two-party affair with electoral wind blowing this way and that between Labour and the Conservatives, while the Liberal Democrats generally struggle for air.

The Liberal Democrats have just three seats in a region with more than 60, way below their national performance levels.

If we really are now entering a period of genuine multi-party politics, some of these old assumptions will have to be set aside.

UKIP has already confounded predictions that its support would ebb away after last May's European elections in which they won three of our region's seats - ahead of both Labour and the Conservatives, who secured two each.

The Conservatives' Warwickshire North MP Dan Byles is stepping down in May

UKIP certainly picked up most of their votes at the expense of the Conservatives, but in the council elections held on the same day they also drew support from Labour sufficient to prevent the larger party from winning instant majorities in places like Tamworth, Worcester and Ed Miliband's self-proclaimed "must win" Walsall council.

Official opposition

These places are all vitally important in our roll call of key general election marginals with which we will all become increasingly familiar during the four months leading up to polling day.

But it is not just UKIP making waves. The Green Party has now amassed 25 councillors in 10 Midlands local authorities, including Solihull where they are now the official opposition.

But perhaps the operative word for the last few paragraphs was "if".

Not all observers are convinced we are witnessing a watershed moment at all. Some commentators point out that in 2010 about two-thirds of the electorate voted for one or other of the two main parties.

That broadly is where their poll rankings put them now. The theory goes that what's happening is a modest redistribution to UKIP and the Greens of that element of the so-called "protest vote" which used to benefit the Liberal Democrats.

HS2 was identified by some people in Coleshill as a vote decider

Nick Clegg's party can no longer be considered "none of the above" because after five years in government the Lib Dems are now clearly "one of the above".

Broadly the theory goes that far from entering a new era of permanent electoral climate change, we are in reality heading back towards a Parliamentary weather system much more akin to the 1970s.

Then, the two main parties were generally nip and tuck before the dawning of the Thatcher/Major and Blair/Brown periods when first one party and then the other enjoyed long periods in office.

But one factor clearly means this time is different.

Never in living memory have we gone into a general election in which each of the two biggest parties, both short of Commons majorities, have their own rival sets of marginal seats which they must target in some cases and defend in others.

This means we have an unprecedented number of potential swing seats in contention.

High-speed rail

Just below Warwickshire North on our list of seats currently held by the coalition partners comes nearby Solihull, itself a prime Conservative target.

The 12 most marginal Conservative and Liberal Democrat constituencies all have majorities under 4,000.

But Labour have even more precarious majorities to defend.

Factor-in to these numbers the variegated, differential, pull of UKIP and Green support, irrespective of whether or not they succeed in winning seats of their own, and you can see why trying to predict outcomes is such a challenge for the experts.

So I turned instead to some of the people who will decide the issue. Perhaps my own informal Q and A session with passers-by in Coleshill town centre might produce some clues.

What, I wondered, were the main factors that would decide their vote on 7 May?

"Immigration", said one. "Immigration and the Economy", said another.

"High-speed rail" was the answer from a man whose home is on the proposed route. But another local told me she was hearing of people moving into the area from the South precisely because of the promise of HS2 which she said was starting to drive up property values.

There's nothing remotely scientific about this of course: just some random straws blowing in the North Warwickshire wind.

And we can be sure those all-important weather vanes have plenty of storms to point out, between now and polling day.

- Published5 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015