Recording lifeboat crews with a Victorian camera

- Published

Women like Leafy Dumas, from West Mersea's crew in Essex, also volunteer for the RNLI

A lifeboat enthusiast has set about recording the country's RNLI volunteers using Victorian photographic methods.

Quietly spoken, Jack Lowe is a man on the verge of his dreams.

A life-long love of photography and lifeboats has finally put him on the road around Britain's coast.

Having given up the Newcastle printmaking business he ran for 15 years, he plans to record all 237 of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution's stations on glass plates with a 110-year-old camera.

"It was like stepping towards the edge of a cliff and hoping that your flying suit would work," he says.

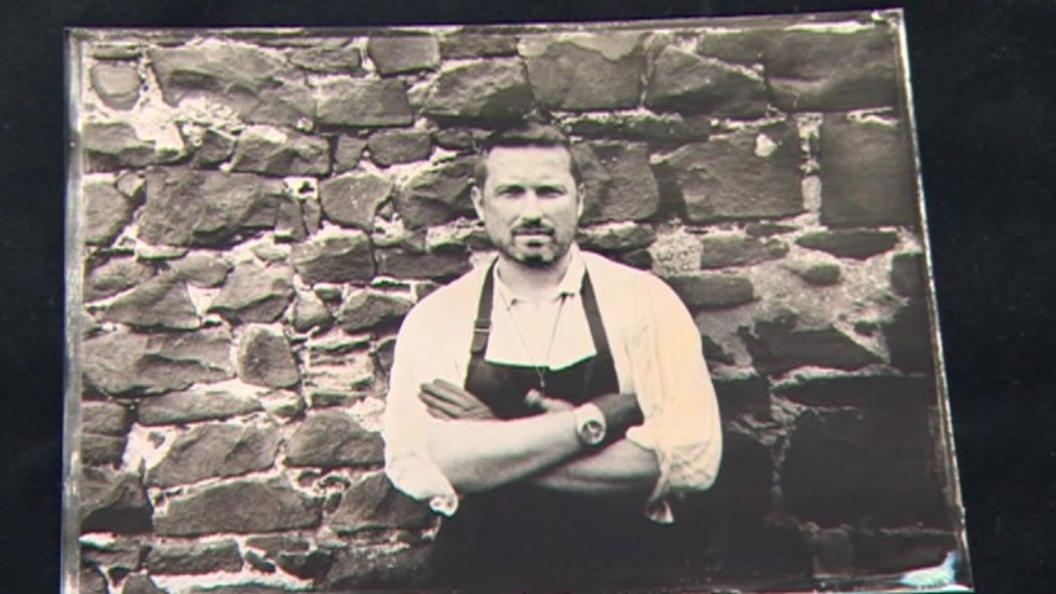

Jack Lowe says the project "aims to share a really important slice of British life"

"I wanted to make things again, things that are actually photo-graphy, drawing with light," he says.

"Making light interact with chemicals and having a physical object people can refer to in 100 years' time.

"The second thing is engagement, participation. It becomes a collaboration because their time is no more or less valuable than my time and we make it together.

"Not only that, but they see within seconds the image appear. So they get an instant bit of reward for their efforts."

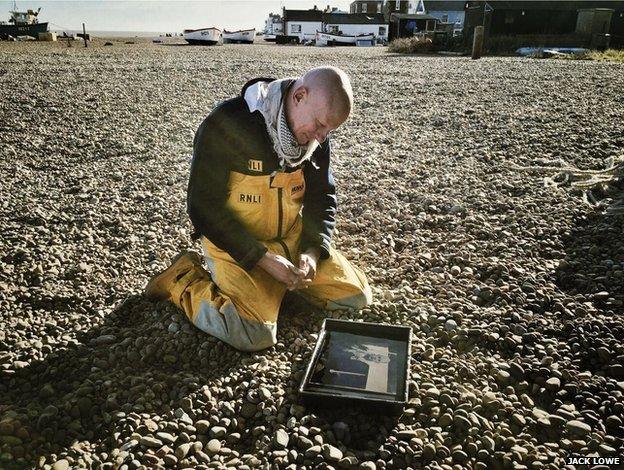

Aldeburgh coxswain Steve 'Tag' Saint and Jack Lowe were "speechless" as the image appeared through the fixing solution

Jack, 39, is quietly delighted by the effect the result has on its subjects.

"Sometimes they're moved to tears," he says.

"Tag, the Aldeburgh coxswain, we were just there together. His eyes welled up when he saw it appear out of the chemicals.

"You pour fixer on the image and it switches from negative to positive before your eyes - magical."

Steve Saint kneeled looking at his image for "quite some time", Jack says

Joanna Quinn, from the RNLI, says the crews photographed so far have found it an "involving and exciting experience".

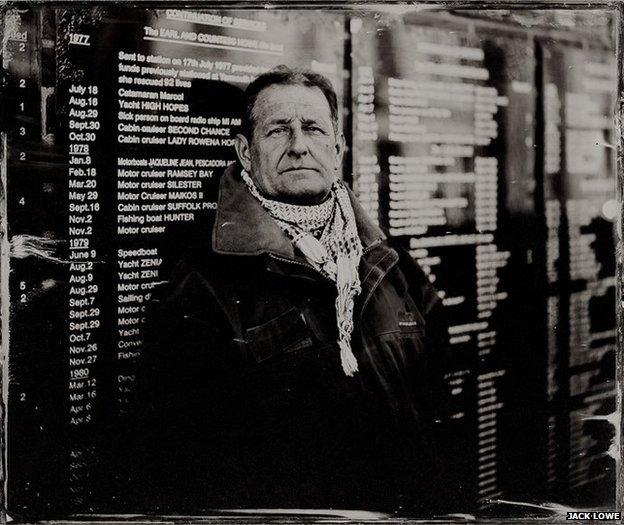

"It's hard to articulate why the pictures are so effective but I think it's something to do with the fact that they look quite timeless," she says.

"Lifeboat crews, though they change through the years - there are more women now, for example, than there ever have been - what they do has always been consistent.

"They are always willing to go out and save lives at sea and I think that continuity and that history is something that's reflected in his pictures."

This is the RNLI that "captivated" the eight-year-old Jack.

Living on a boat at Teddington and Ramsgate harbour probably helped.

As did visiting his dad on the Isle of Wight and seeing where Atlantic 21 lifeboats, which he thought were "so cool", were made.

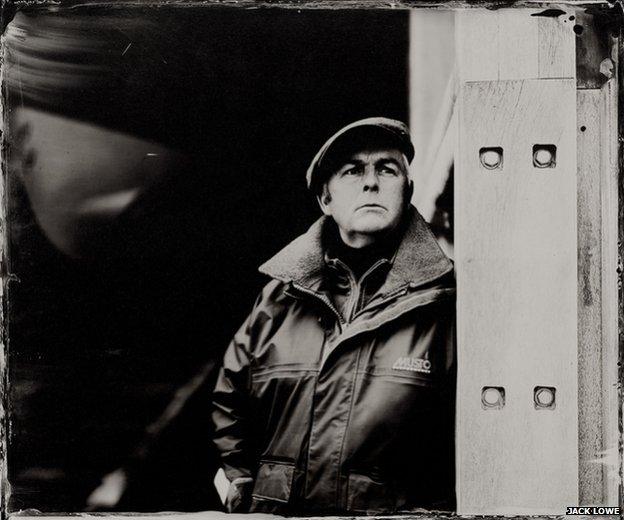

Jack tells crews like the team at Clacton-on-Sea that they are "making a piece of work together"

Jack spends at least a day at the lifeboat stations and the Victorian process he uses is not swift, like the instant click of a digital shutter.

An image is produced on a glass plate - coated with chemicals and still wet - when it is exposed to light through the camera.

A fixative stops the process and sets the picture - known as an ambrotype.

Jack Lowe uses a Thornton Pickard to make his images

Having converted his bedroom into a dark room at the age of 12, it is perhaps not surprising that Jack has done the same to an old ambulance, called Neena.

The process has to be started and finished in about 15 minutes, unlike rolls of film which can be developed later, so he needs facilities to hand.

Neena parked at St Abbs, the first Scottish station to be documented by the project and which will be closed as part of a review of the Northumberland and Scottish Borders coastline

The less light there is - specifically UV - the longer the camera's shutter has to remain open. If the subject moves, the image will blur.

"These are four, five, six, seven-second exposures," Jack says. "It makes for beautiful work because they have a peace about them.

Walton and Frinton retired coxswain Gary Edwards

"You have captured a few seconds in the glass. They've been thinking things and their hearts have been beating."

With exposures of up to 12 seconds, willing participation is essential.

An overcast location and the need to walk repeatedly between camera and dark room along a 150m (300ft) pier meant it took far longer than usual to photograph Cromer coxswain John Davies.

"John isn't known for his patience with photographers," Jack says.

Fading UV light conditions require longer exposures - with the subject staying completely still - and it took more than four hours to produce this image of Cromer coxswain John Davies

"But there was a moment after about two and a half hours where he could tell that I was as dejected as he was.

"I just sat down and put my head in my hands and I said, 'I'm really sorry about this John'.

"He said to me - out of the blue, I didn't expect this at all - he said 'don't worry Jack, we'll crack this'.

"This is an eighth generation Cromer coxswain. He's been at sea since four in the morning. He's the only one in the station. He's just there for the photograph."

Jack says he had wanted to take this picture of Cromer slipway since he was a boy and a member of Storm Force, the RNLI's junior membership scheme

Jack's intention is for the RNLI to own the completed collection of glass ambrotypes, which the organisation says "would be a remarkable thing" for it to have.

It is committed to sharing them with as many people as possible, through an exhibition, book or gallery, it says.

Jack gives the first print from each ambrotype to the station or crew member and pays for the project - and "puts food on the table" - by selling further prints to anyone who wants them.

With a loose rule of thumb to go north when it is warm and south when cold, he expects to visit Scotland next.

And then, one day, after the four or five years his project will take, he will become a lifeboatman, he says.

"I will be. I know I will be," he says.

- Published1 July 2014