'Too frightened to leave and hating to stay'

- Published

Balakrishnan's daughter told the BBC's Tom Symonds: "He wanted the whole world to be like the collective where he is in charge and everybody is his slave"

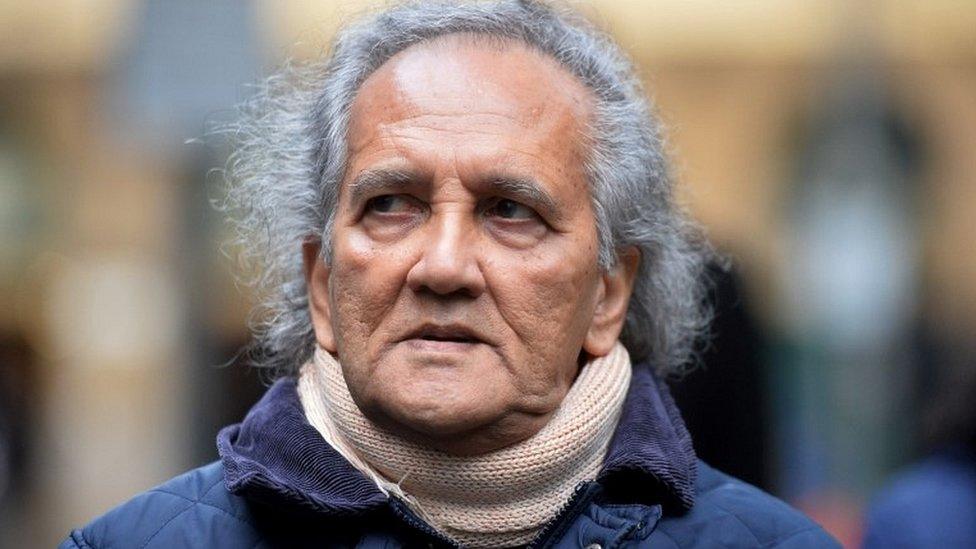

For more than 30 years, cult leader Aravindan Balakrishnan convinced his victims he was "all powerful and all-seeing" - a master manipulator who used violence, fear and sexual degradation to control the women he held captive in communes across London.

His daughter was one of them.

Born into her father's Communist "collective", she spent her childhood almost entirely isolated from the outside world.

She never went to school or played with a friend her own age, but spent years cooped up in the various houses occupied by the group.

Southwark Crown Court heard how, as a child, she was so painfully alone she spoke to the taps and toilet for company - hugging them for being "nice" to her.

On one occasion, she was so desperate to see an unfamiliar face she fabricated a water leak in an airing cupboard in the hope someone would come to fix it.

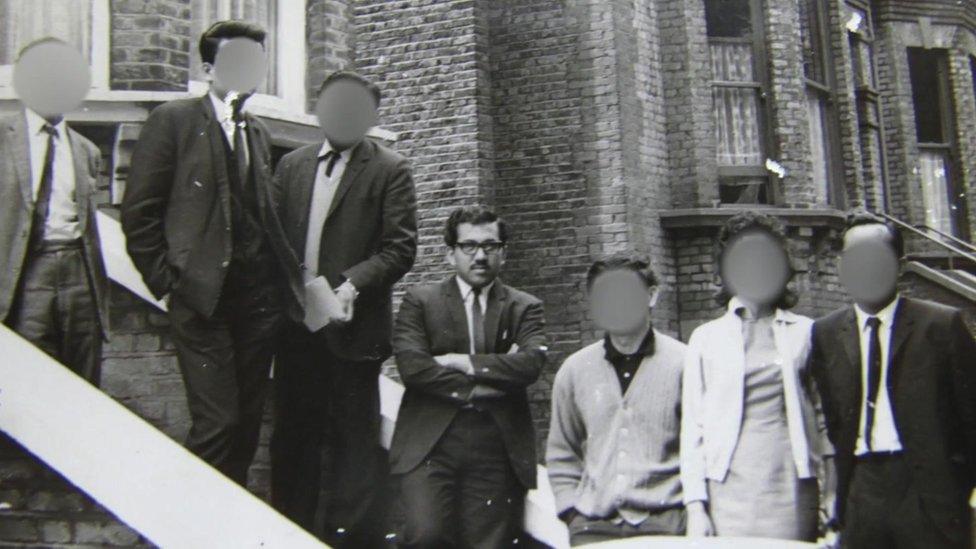

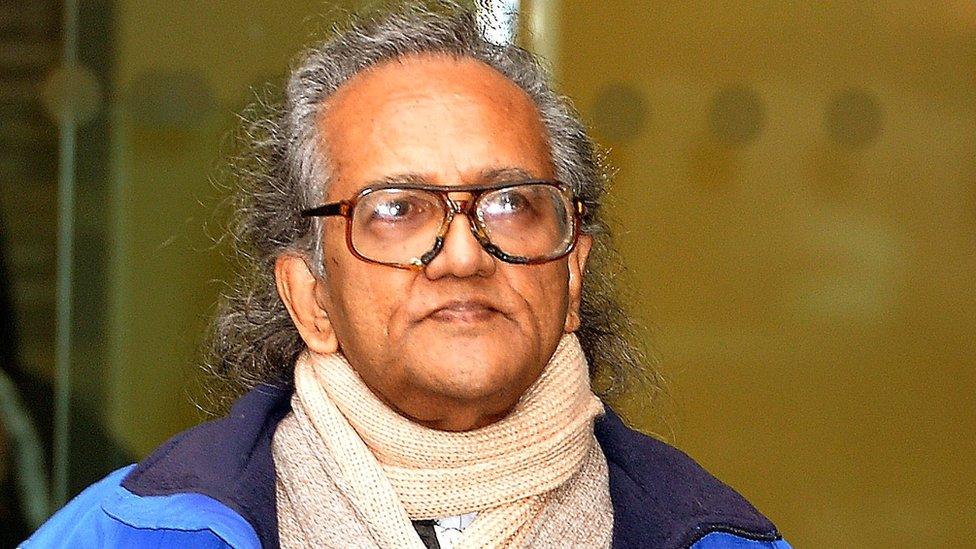

Aravindan Balakrishnan, centre, moved to London in the 1960s where his speeches earned him a reputation as a "charismatic man"

This was the sad picture painted in the diaries of a girl who was kept in captivity most of her life.

But how did this happen?

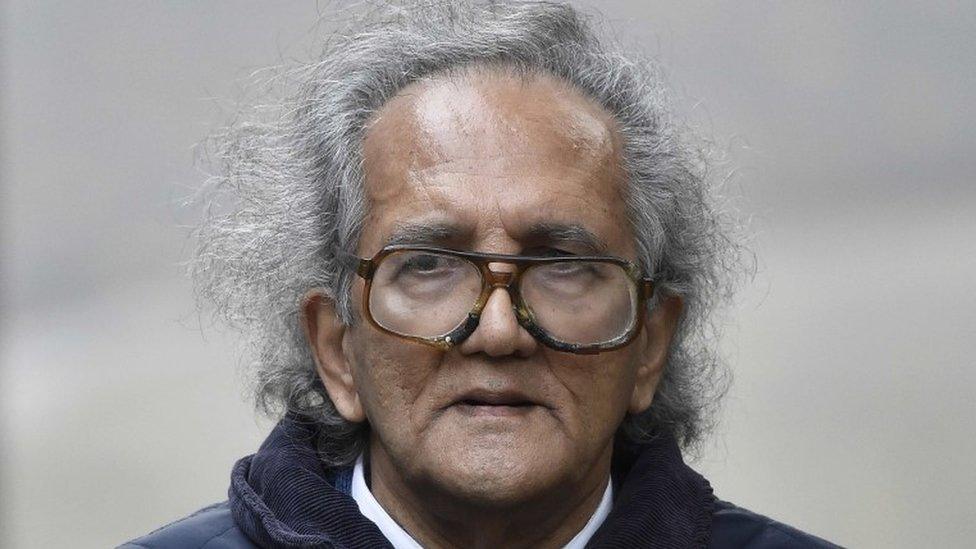

At Aravindan Balakrishnan's trial, jurors heard how the cult leader likened himself to God and believed himself to be the "centre of the natural world".

Through a brutal regime of violence and sexual degradation, he sought to mould his followers into a "cadre of women soldiers" he believed could help him overthrow "the fascist state".

There were rapes and victims were beaten and told "bad ideas could burn you to death". He made it, the prosecution said, so they were "too frightened to leave but hated to stay".

To those with the luxury of free will, the fact these women stayed might seem baffling.

But Graham Baldwin, manager of Catalyst Counselling, which supports victims of cults, said those caught up in Balakrishnan's web would have been taught to believe their lives were "satisfying".

"What normally happens is a leader says: 'I've got special knowledge, I know how to make your life better and the world better but you've got to do what I say'," he explained.

"Then it becomes a process of breaking down a person's ego, so that he is incompetent. They are told they are the new world order and this is their great moment... [and] if they leave the group or betray it then God is going to punish them."

Balakrishnan started the "Workers Institute" in a building in Acre Lane, Brixton

Jurors heard Balakrishnan's political views were influenced by what he saw as post-war British mistreatment of the people of Malaysia and Singapore, where he lived from 1949.

He moved to London in the 1960s and began giving political speeches, earning a reputation as a "charismatic man" whose ideals struck a chord.

It was the height of the Cold War and a period when the UK had a plethora of small left-wing collectives and communes.

The many empty houses of south London in particular were targeted by left-wing groups for the purpose of collective living.

"It had been a worrying and oppressing time and finding someone a bit like you, who has the same idea about the world you want to live in, living with them was not so unusual," said historian Dr Lucy Robinson.

"It was a time when all sort of ideas were up for grabs. People did go out and make their own politics.

"[But] this [case] is not a lesson about communes and counter-culture, but a lesson about abuse, because you could normally just leave a commune."

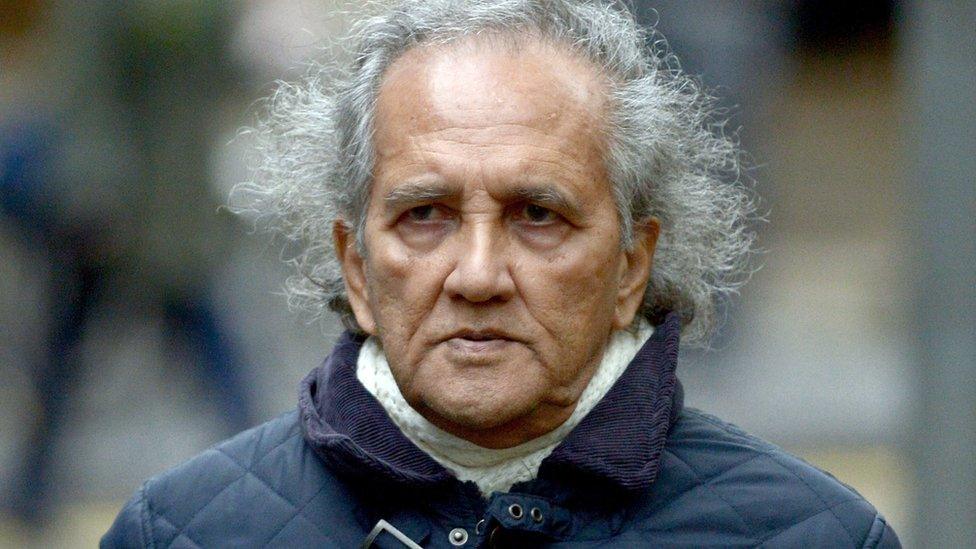

Aravindan Balakrishnan likened himself to God and convinced his followers he was the "centre of the natural world"

Balakrishnan and his wife Chandra ran a bookshop and commune from a large building in Brixton, where he started his so-called "Workers Institute" in 1974.

He initially claimed his teachings were based on those of Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong but by 1980 the "collective" had evolved into a "Cult of Bala", far removed from its original ideals.

Only a handful of women remained and were kept under Balakrishnan's strict control - prevented from seeing family members and governed by a strict rota of work and chores.

Regular beatings eventually evolved into the sexual abuse of at least two women, who Balakrishnan claimed were being "purified" or "cleansed" by the acts he forced upon them.

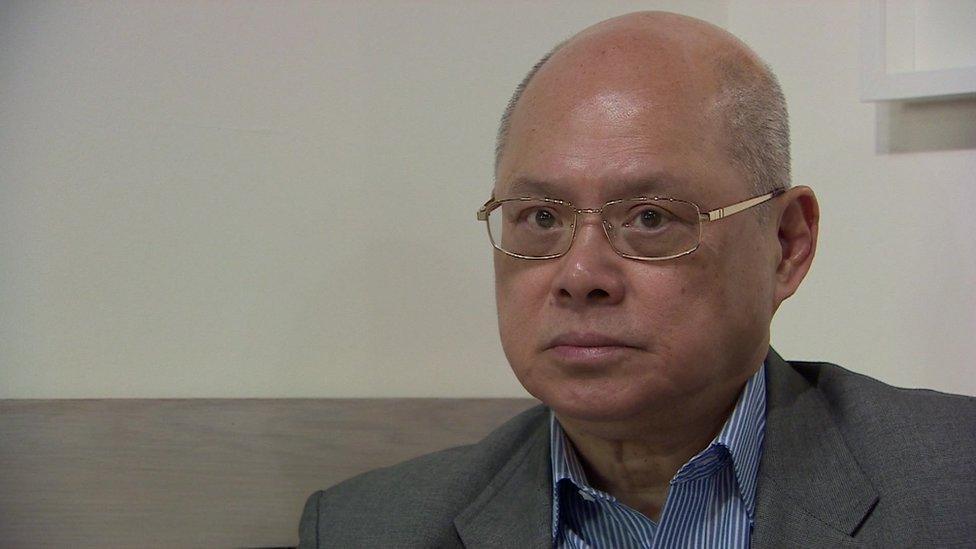

Stephen Chang attended a number of political talks given by Balakrishnan between 1968 and 1971

His appearance [now] does not reflect in any way who he was.

In the early days he was well groomed, he was smart, he took great care of his hair, the way he wore his glasses, the way he conducted himself.

He was extremely knowledgeable and a great orator... but in his environment, we began to realise you didn't have a choice, you had to listen to what he said.

That's when my relationship broke up with him.

He's definitely a psychopath, I have no doubts about that. He has all the characteristics of a psychopath - they have no remorse, no guilt, they're manipulative, they have a great sense of self-grandeur, they have objectives that are totally unrealistic.

He meets people, he impresses them with his knowledge and storytelling skills, he gleans info about their private lives and uses that to create doubts within that individual and their capabilities and makes them emotionally dependent on him, like a cult leader.

Balakrishnan's daughter was born into the collective after one of its earliest members, Sian Davies, became pregnant.

But the girl's status as the youngest member of the commune did not save her from physical punishment and she lived in perpetual fear of incurring the wrath of "Jackie", a mind control machine the defendant claimed had the power to torture her.

She lived in fear of her father's "Jekyll and Hyde" character: "When he was nice, he could be very nice, but when he was not he was frightening," the court heard.

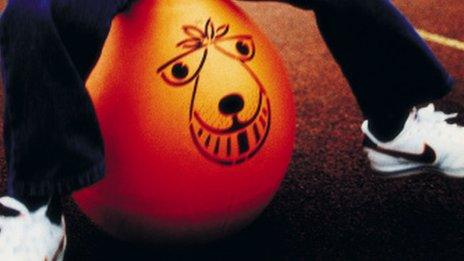

Speaking to the BBC, she recalled an incident in which the defendant took away her balloon when she was 10 years old.

"He punctured it because I liked it. He said: 'This is really good because I can use the stick to whip you'."

It was against this backdrop that Balakrishnan, now 75, was able to oppress his victims for so long.

The court heard his views were "so deeply instilled in them all they were too scared to oppose him".

Mr Baldwin said that, far from being unintelligent, the kind of person often caught up in a cult tends to be bright but idealistic.

He said some fall victim very quickly and, in one case the charity dealt with, a gap-year student was recruited into a cult during a 12-hour flight stopover in New York.

But, he warned, it can take much longer to leave.

Yvonne Hall and Gerard Stocks of the Palm Cove Society, which rescued the women

"We have spent a lot of time working with them and the progress has been outstanding; [the daughter] is very competent and is looking at moving to independent living and she's studying at college," said Ms Hall.

"They were all told the outside world was a very hostile place and if they went out bad things would happen to them: they would get killed or raped or disappear. The youngest one was told if she left the property she would spontaneously combust.

"[When the daughter came out] she wasn't able to navigate from A to B, she wasn't able to use public transport or go shopping independently, or do day-to-day activities that a normal 30-year-old could do."

Mr Stocks added: "She couldn't cross the road. It took us two-and-a-half weeks to teach her how to do that herself and now she can get about just fine, but when she came out it was very different.

"We're looking at a man who manipulated and controlled people to a height none of us can really imagine."

For Balakrishnan's daughter, it was only when she reached her 20s that she began to realise the extent of her confinement.

She started fantasising about men and developed a crush on a neighbour. Though she never spoke to him, she was devastated when the commune moved to another estate, writing in her diary: "I was cruelly wrenched away from my beloved darling, I have never [had] anything to look forward to."

An infatuation with a second neighbour turned into a sexual relationship - he would climb through a window to visit her - but this ended when Balakrishnan caught them and beat her.

She believes she suffered a miscarriage a few weeks later.

Three women eventually escaped from a property in Peckford Place, south London, where the collective was living

Fed up with being "a non-person", in 2005 she plucked up the courage to flee the commune.

Ill-equipped to cope in the outside world, she went to a police station - where she was told to go back to the collective or risk being reported as a missing person.

It would be another eight years before she finally managed to escape for good - by that point seriously ill with diabetes - setting off the chain of events that would lead to her father's arrest.

Now 32, she is no longer at the mercy of the man who for years she knew only as Comrade Bala, and the note she left him the day she left suggests a woman determined to make up for lost time:

"I may have no wealth, no property, but I do have my dignity and I will defend it with my life," she wrote.

But she also hopes to build bridges with her father.

"I forgive him and I would like to reconcile with him in the future, because hatred does no good to anyone," she told the BBC.

"Nelson Mandela said if you leave a place with anger and hatred and bitterness, then you are still in prison and I don't want to be in prison that way."

Additional reporting: Beth Rose

- Published4 December 2015

- Published4 December 2015

- Published30 November 2015

- Published26 November 2015

- Published25 November 2015

- Published19 November 2015

- Published18 November 2015

- Published17 November 2015

- Published13 November 2015

- Published12 November 2015

- Published27 November 2013

- Published16 April 2012