The imminent death of the Cavendish banana and why it affects us all

- Published

More than 100 billion bananas are consumed each year, making it the fourth most important crop after wheat, rice and corn

Buy a banana and it will almost certainly be descended from one plant grown at an English stately home. But now we face losing one of the world's most-loved fruits.

Sitting in picture-perfect Peak District grounds, Chatsworth House seems an unlikely birthplace for today's global banana industry.

But practically every banana consumed in the western world is directly descended from a plant grown in the Derbyshire estate's hothouse 180 years ago.

This is the story of how the Cavendish became the world's most important fruit - and why it and bananas as we know them could soon cease to exist.

The birth of the Cavendish banana

Chatsworth House in the Peak District is still home to the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire

Bananas have been grown at Chatsworth since 1830 when head gardener Joseph Paxton got his hands on a specimen imported from Mauritius.

He had apparently been inspired after seeing a banana plant depicted on Chinese wallpaper in one of the home's 175 rooms, but today's head gardener Steve Porter is sceptical about the story.

"Certainly the timings fit", he said, "but I think it's much more likely that Paxton was always on the lookout for new and exotic plants and was well connected enough to know when the banana plants arrived in England."

Paxton filled a pit with "plenty of water, rich loam soil and well-rotted dung" with the temperature maintained between 18C and 30C (65F and 85F) to grow the fruit he called Musa Cavendishii after his employers (Cavendish being the family name of the Dukes and Duchesses of Devonshire).

"At that time for a family in England to be able to grow their own bananas to feed their guests was very exciting," said Mr Porter, adding: "It still is for us today."

Chatsworth's head gardener was apparently inspired to grow the banana after seeing a depiction of the plant on wallpaper in the house

In November 1835 Paxton's plant finally flowered and by the following May it was loaded with more than 100 bananas, one of which won a medal at that year's Horticultural Society show.

A few years later the duke supplied two cases of plants to a missionary named John Williams to take to Samoa.

Only one survived the journey but it launched the banana industry in Samoa and other South Sea islands (Williams himself was killed by natives).

Missionaries also took the Cavendish banana to the Pacific and the Canary Islands.

So the Cavendish spread, but it is only in relatively recent years that it has become the exporter's banana of choice, its rise in popularity caused by the very thing that is now killing it off - Panama disease.

Bananas on the brink

Bananas are native to south and south-east Asia, although there are plantations around the world

For decades the most-exported and therefore most important banana in the world was the Gros Michel, but in the 1950s it was practically wiped out by the fungus known as Panama disease or banana wilt.

Banana growers turned to another breed that was immune to the fungus - the Cavendish, a smaller and by all accounts less tasty fruit but one capable of surviving global travel and, most importantly, able to grow in infected soils.

Though banana-growing habitats still have their own breeds, practically all bananas exported to foreign markets such as Europe, the UK and North America, are Cavendishes, clones of the first Chatsworth plant.

And a quarter of the bananas eaten in India are Cavendishes while practically all the bananas sold and consumed in China are descended from Chatsworth's plant.

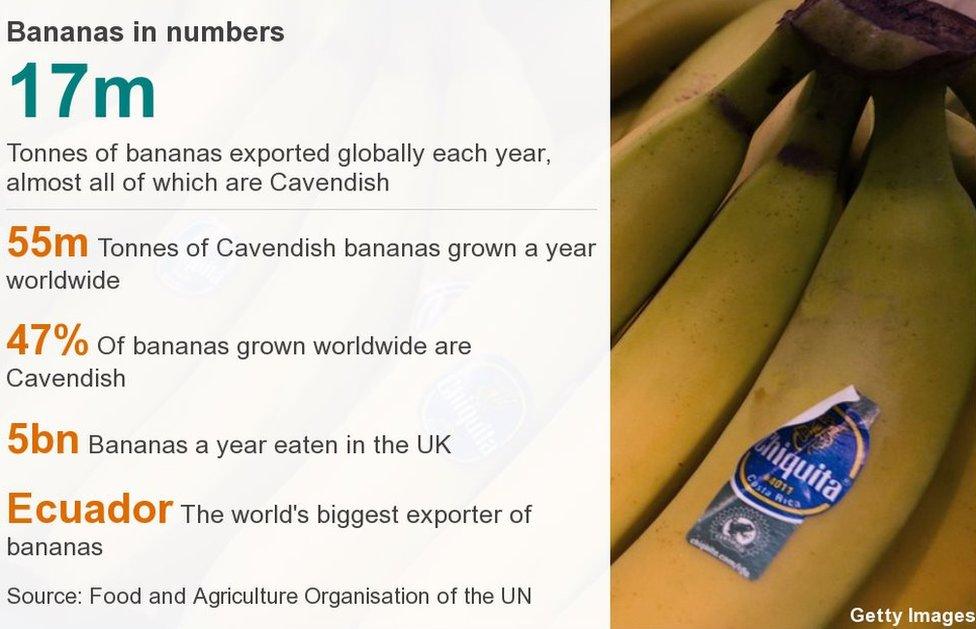

Bananas in numbers

17m

Tonnes of bananas exported globally each year, almost all of which are Cavendish

-

55m Tonnes of Cavendish bananas grown a year worldwide

-

47% Of bananas grown worldwide are Cavendish

-

5bn Bananas a year eaten in the UK

-

Ecuador The world's biggest exporter of bananas

But just as breeders were busy cultivating their Cavendishes, so too was Panama disease developing a new strain capable of killing them off.

And the new fungus is even more deadly than that which wiped out the Gros Michel, for it also affects numerous local breeds of banana around the world.

As well as killing off banana plants the Panama Disease also lingers in the soil for decades

"I try to avoid dramatising this story but look at what happened previously with the Gros Michel," said Dr Gert Kema, an expert in global plant production from the Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands.

"If that happens again we have a very serious issue, and it is happening now.

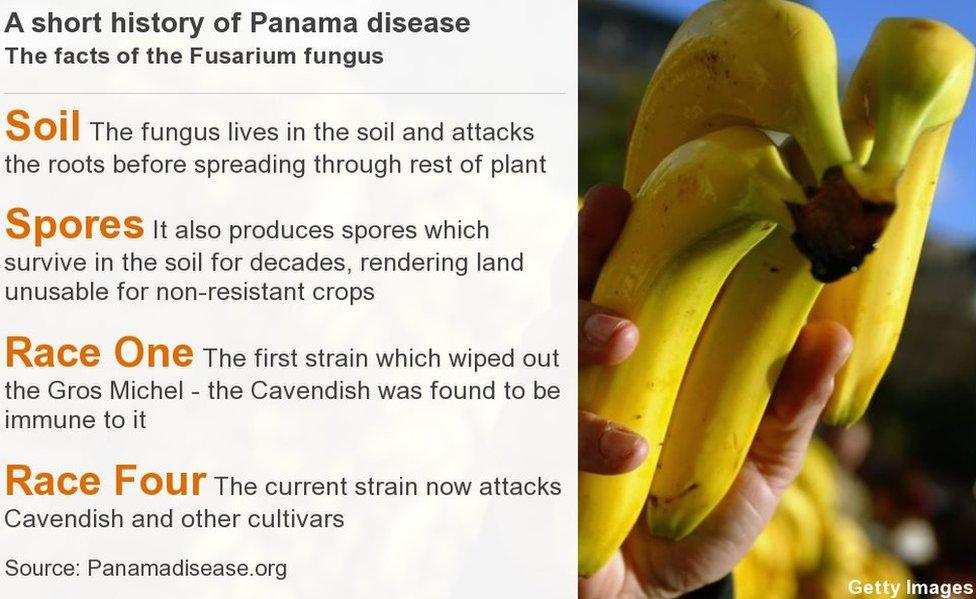

A short history of Panama disease

The facts of the Fusarium fungus

-

Soil The fungus lives in the soil and attacks the roots before spreading through rest of plant

-

Spores It also produces spores which survive in the soil for decades, rendering land unusable for non-resistant crops

-

Race One The first strain which wiped out the Gros Michel - the Cavendish was found to be immune to it

-

Race Four The current strain now attacks Cavendish and other cultivars

"This does not mean that next week there will be no bananas in supermarkets in the UK.

"This is going to take some time but that time is extremely pressing; we have nothing to replace the Cavendish right now."

Some 10,000 hectares of Cavendish have already been destroyed according to Panama Disease.org and experts warn many more will follow if the fungus is not stopped.

How can the banana be saved?

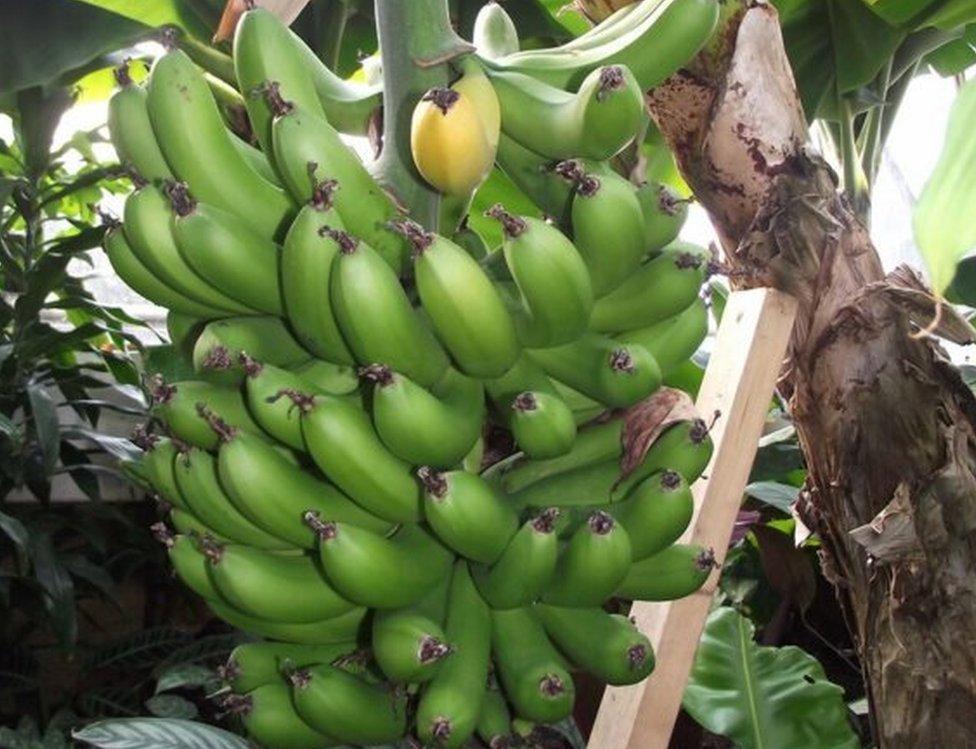

There are numerous local breeds of banana around the world but by far the most exported is the Cavendish

The solution to the banana crisis is twofold, according to Dr Kema.

First, contain the epidemic, but that's much easier said than done, says Alistair Smith, international co-ordinator for Norwich-based Banana Link, a co-operative that works with growers and farmers around the world.

"It is more or less possible to contain with very strict measures but there is nothing to say [Panama disease] is not going to arrive somewhere else, for example from contaminated soil on boots or via an infected plant, and there is no way to salvage your production once you have got the disease.

"It's a huge issue for growers who have already been affected in places like the Philippines but awareness is only now growing in the Americas who are yet to be hit.

In many countries bananas are a vital food source and key business

"The potential for devastation if it does reach them is almost total."

And how practical is containment when the fungus can easily be transmitted by natural means such as storms?

"We have much more advanced technology now than we did when we lost the Gros Michel," Dr Kema said.

"We can detect and track the fungus far better than we could but the underlying problem is still the same in that the Cavendish is so vulnerable to disease, and that has to change."

As well as destroying large swathes of banana plants, typhoons and other storms of the sort seen in Asia can also carry the Panama disease fungus to new plantations

And that's the second solution - find a new banana resistant to the disease and, to avoid history repeating itself, genetically diverse.

"To carry on growing the same genetic banana is stupid," Dr Kema said.

"It is necessary that we improve the Cavendish through genetic engineering but parallel to that we must be finding genetic diversity in our breeding programmes."

And it is vital we keep the banana says Adam Hart, professor of science communications at the University of Gloucestershire, not only because it is crucial to numerous countries' economies but also because it is popular.

"Culturally the banana has become quite important, it is seen as a power fruit with plenty of sports people pictured eating them, it is nature's convenient snack.

Bananas are seen as a power food popular among sports people and the health conscious, says science communication professor Adam Hart

"The world would carry on if we lost bananas but it would be devastating for those who rely on it economically and very sad for those of us who enjoy eating them."

Meanwhile, oblivious to the global catastrophe their cousins are facing, Chatsworth's plants continue to produce between 30 and 100 bananas a year to be eaten by the Cavendish family and their guests.

"They are more like a plantain, denser and not as sweet," said Mr Porter, "but they are displayed in bowls and used in cooking in the house.

"Whatever happens in the rest of the world, we will do everything we can to keep our own bananas growing."

Chatsworth is still growing plants descended from Paxton's 1830 purchase with the bananas still used in the house

- Published13 September 2015