Jutland Jack: The life and death of a boy sailor

- Published

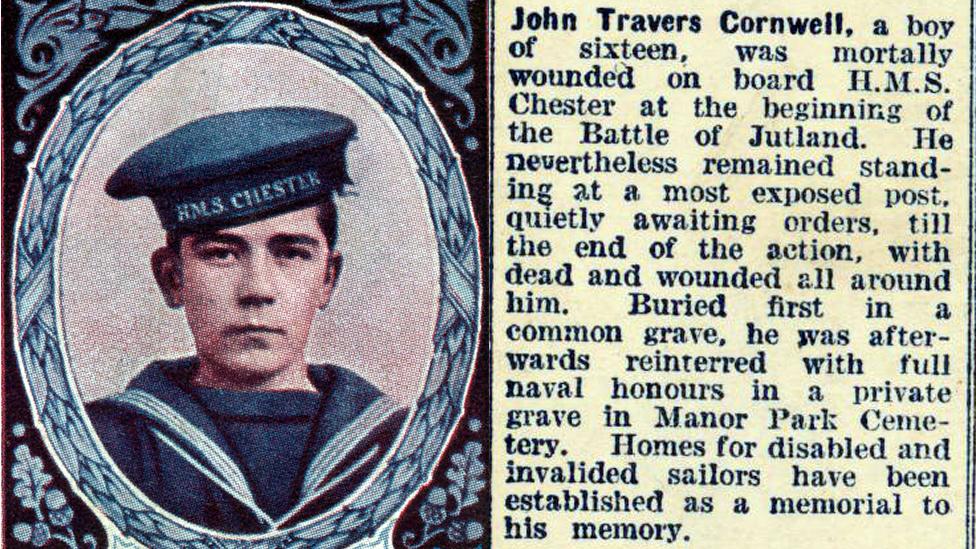

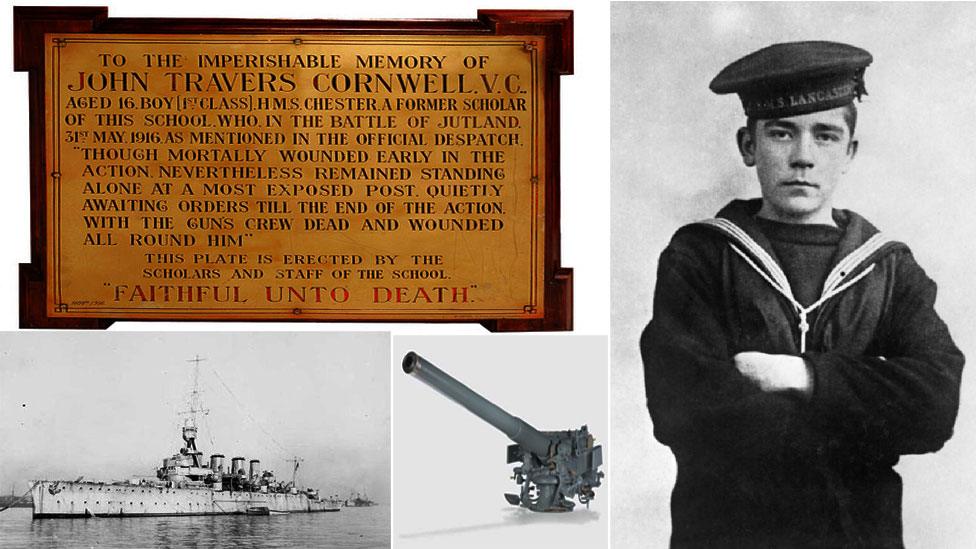

Jack Cornwell was only 15 when he joined the Royal Navy - and only 16 when he died less than a year later. The Battle of Jutland - a 72-hour onslaught 100 years ago - was his first encounter with the enemy, and his last.

The working-class lad was the youngest recipient of the Victoria Cross in World War One; the highest military decoration awarded for valour in the face of the enemy.

So what is the story of Jutland Jack?

Boy sailors would help man the guns and keep the deck clear

When Lily Cornwell received a letter from doctors at a hospital in Grimsby telling her of her 16-year-old boy's injuries, she immediately travelled north from her home in London to see her son.

But Mrs Cornwell was still on the train when Jack died. All she could do was take his body home - and because the Cornwell family was not well off, have him buried in a communal grave.

Tragic though it was, it wasn't unusual. That quiet end might have been the last the world heard of Jack Cornwell, Boy Seaman First Class.

But three months later Capt Robert Lawson, the captain of Jack's ship, described the events to the British Admiralty.

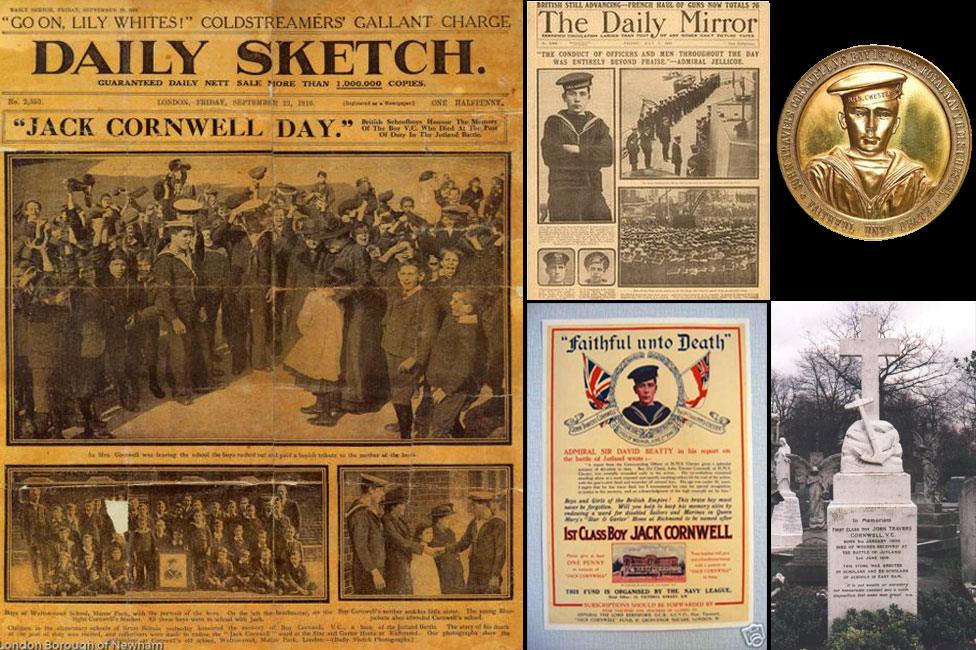

Jack's story and funeral made the front pages of newspapers

On 30 May 1916 the Royal Navy's fleet put to sea. The following day German ships also steamed out into the North Sea.

British sailors spotted distant ships at 14:00. It was the German fleet, off Jutland in Denmark.

The first shots were fired at 14:28. The Battle of Jutland had begun.

The Germans rained shells upon the fleet. After firing just one salvo, HMS Chester was badly damaged. The forecastle received a direct hit, killing or wounding every member of Cornwell's gun crew.

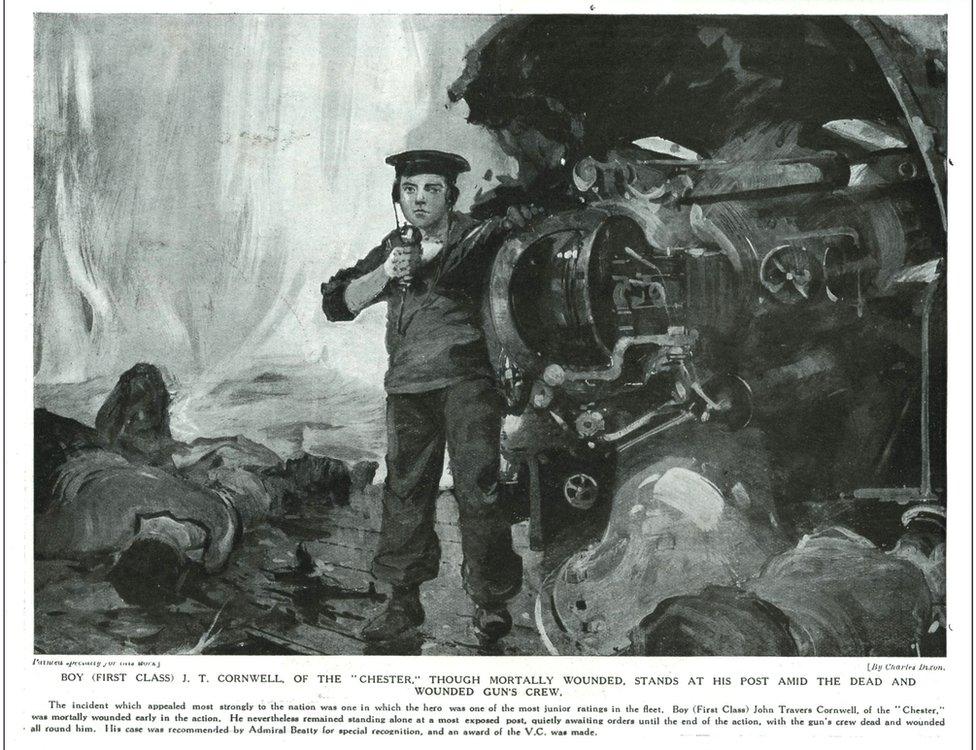

Jack's story captured the public's emotion and many paintings and drawings portray the afternoon he stood fast at his gun

Onboard, mortally wounded and surrounded by the dead and dying, Jack took orders via headphones from an officer on the bridge. He was fully responsible for setting the gun's sights, and his speed and precision would determine whether they were to hit or miss their target.

He was bleeding heavily from a hole smashed in his chest where he'd been hit by a jagged shard of searingly hot metal. Shells hurled down on the cold waters; splashes and smoke making it impossible to see. But he never deserted his post.

When rescuers found him he was barely alive. Two days later, he died.

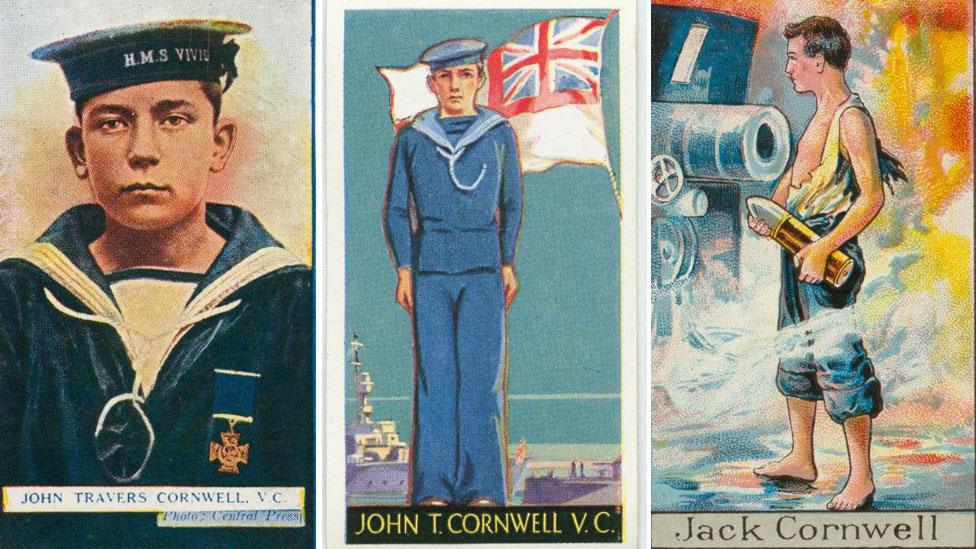

Jack was portrayed in several series of cigarette cards, including Young Heroes

Born in 1900 to Lily and Eli, a tram driver, John Travers Cornwell grew up in Leyton, Essex with his parents, brothers Ernest and George, sister Lily, stepbrother Arthur and stepsister Alice. He soon became known to his family as Jack.

When he left school in 1913, he got a job as a delivery boy for tea company Brooke Bond & Co. and then worked as a dray boy with the Whitbread's Brewery.

But ordinary life stopped when war broke out.

Eli Cornwell joined the Army, and Jack tried to join the Navy - but was rejected because he was too young to do so without his parents' permission. Undeterred, he tried again in 1915, this time giving the names of his boss at work and his old headmaster as referees. He was accepted.

After training as a gun layer he joined the crew of HMS Chester with about 400 other men. He was given a number of J/42563 and the rank of Boy Seaman First Class.

The gun Jack manned can be seen at the Imperial War Museum

After Jack died, Capt Lawson also found the time to write a heartbreaking personal letter to Lily Cornwell, concluding: "I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost from this world.

"No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but to assure her of what he was and what he did, and what an example he gave."

It was an emotion that echoed across the country.

Jack's story was told in newspapers, magazines and books - the Daily Mirror's front page described the "bravery of John Travers Cornwell".

Jack's brother was often used as a stand-in model for paintings

When the fact of his humble burial became known, public opinion led to his disinterment from the original grave and reburial with full military honours at Manor Park Cemetery, where his grave has just been awarded Grade II-listed status by Historic England.

The funeral route was lined by Boy Scouts and attended by tremendous crowds. Jack's family walked in the procession with 80 members of Jack's old school, Boy Scouts, Sea Cadets, and six Boy Sailors from HMS Chester.

It was then that Jack truly became famous - although there were few pictures of Jack, artists improvised by using his brothers Ernest and George as stand-in models. His image appeared everywhere, on collectors' cards, packaging and posters.

Jack's medals have a blue ribbon, which signify he was in the Navy

A ward at the Star & Garter Home at Richmond, which looked after injured servicemen, was named in Jack's honour.

The Scouts set up an award in his name, which still exists today. The Jack Cornwell Badge recognises devotion to duty, courage and endurance.

The gun Jack stuck to so valiantly can be seen at the Imperial War Museum, and his medal was also given to the museum by his sister.

Eli Cornwell, weakened by trench warfare, succumbed to bronchitis and died in 1916. Jack's older stepbrother Arthur was killed in action in 1918.

Lily Cornwell didn't have long to mourn all of her losses. She died destitute in 1919.

Complete letter from Captain Robert Lawson of HMS Chester to Mrs Lily Cornwell, Jack's mother:

"I know you would wish to hear of the splendid fortitude and courage shown by your boy during the action of May 31. His devotion to duty was an example for all of us.

"The wounds which resulted in his death within a short time were received in the first few minutes of the action. He remained steady at his most exposed post at the gun, waiting for orders.

"His gun would not bear on the enemy, all but two of the ten of the crew were killed or wounded, and he was the only one who was in such an exposed position.

"But he felt he might be needed - as indeed he might have been - so he stayed there, standing and waiting, under heavy fire, with just his own brave heart and God's help to support him.

"I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost from this world. No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but to assure her of what he was and what he did, and what an example he gave.

"I hope to place in the boys' mess a plate with his name on and the date, and the words 'Faithful unto death.'

"I hope some day you may be able to come and see it there."

Able Seaman Alexander Saridis, great-great nephew of Jack Cornwell, visits the grave at Manor Park Cemetery

- Published8 January 2014