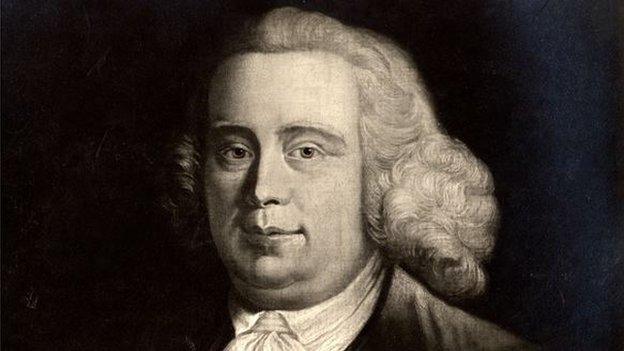

James Brindley: The canal pioneer who changed England

- Published

James Brindley's early career focused on building and repairing mills, where he learned to control water flows

A new exhibition marking 300 years since the birth of canal pioneer James Brindley has opened. How did his work transform the English landscape and unlock a new era in the Industrial Revolution?

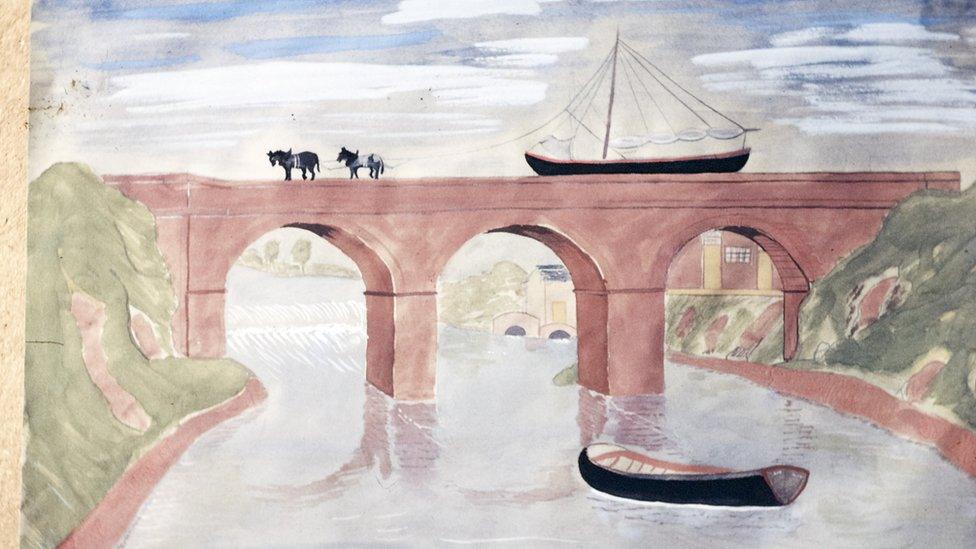

When James Brindley sought Parliament's backing for his plan for an aqueduct over the River Irwell in Lancashire, he apparently employed a novel means of gaining their attention.

Taking out a block of Cheshire cheese, the man who engineered England's first canal carved out a model of the waterway he hoped to build.

"It's not clear if he cut it into pieces and put it in water to illustrate how waterproof troughs worked or if he carved arches to show how an aqueduct could work," said Nigel Crowe, from the Canal & River Trust.

Various accounts suggest Brindley carved cheese to showcase his Barton Aqueduct design to a parliamentary committee

"The other story is he brought in a lump of clay and bashed that into shape.

"If it is true or not, it is a nice bit of fiction."

Born in Tunstead in the Derbyshire hills in 1716, Brindley moved as a child to a farm in Leek, Staffordshire, left to the family by their Quaker relatives.

His early career focused on building and repairing mills in the area, where he learned to control water flows.

![Black and white photograph taken from beside the canal, shows the butty "Sunlight" [built in 1929 by the Anderton Company] in the foreground being towed by the motor "Silver Jubilee" [rebuilt from Anderton Company's horse boat 'Greece']. There is a boatwoman at the tiller of "Sunlight" and a boatman at the tiller of "Silver Jubilee". There are industrial buildings and a crane in the background.](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/DF7B/production/_90511275_potteriesnarrowboatsbw192-3-2-1-30-75.jpg)

Josiah Wedgwood saw the benefits of the Trent & Mersey Canal to the ceramic industry

The quality of his work catapulted him into the national limelight.

A meeting with the Duke of Bridgewater led to the start of the Bridgewater Canal, commissioned in 1759, to transport coal from the duke's mine at Worsley to Manchester.

At the time a pioneering feat, the waterway became recognised as the first still-water canal in Britain.

An earlier canal, the Sankey St Helen's canal had used a river to form the canal to make it more navigable, the Canal and River Trust said.

The building of the Bridgewater Canal's Barton Aqueduct - the structure he had demonstrated with cheese - became his most famous feat, opening on 17 July 1761.

It was the first navigable aqueduct to be built in England and a structure that would stand for another 100 years.

James Brindley made British canals narrow to save water

Over the following decade, Parliament backed the creation of a number of new man-made waterways cutting through England's industrial heartlands.

The Trent & Mersey Canal, Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal, Droitwich Canal, Coventry Canal, Birmingham Mainline Canal and Oxford Canal all began to be developed during this period, the Canal & River Trust said.

Brindley had a hand in all of these but was heavily involved, as engineer, in the Trent & Mersey and Staffordshire & Worcestershire developments.

Spotting an opportunity to transport goods more cheaply and efficiently from his factories in the Stoke potteries, industrialist Josiah Wedgwood became an early advocate of canals and fought hard with Brindley for their construction.

Their work flew in the face of one "gentleman of eminence" - rumoured to be the engineer John Smeaton - who publicly denounced "he had heard of castles in the air but had never before seen where any of them was to be built", according to Victoria Owens, who transcribed Brindley's notebooks.

As well as revealing he spelled words phonetically, the notebooks chronicle his "conscientious" nature and that he was "careful with money", Ms Owens said.

Four of these notebooks spanning 1755 to 1763 have now been uncovered and form part of a new exhibition about his life at the National Waterways Museum, external, Ellesmere Port in Cheshire.

The Brindley 300 exhibition, external runs until 2 October and is among a number of events taking place to celebrate the canal pioneer's life and legacy.

Mr Crowe said there was "no doubt" the Duke of Bridgewater acquired knowledge and books from travels in France which led to the conception of the first British canal, but it was Brindley's contribution that created their "idiosyncrasy".

It was the genius of his construction techniques that have sealed his place in history.

He made British canals narrow, to save water.

The "Brindley lock" allows boats to descend and ascend waterways.

And he used puddle clay to waterproof the base of the canals.

Lord Rusholme on the inspection launch Lady Hatherton on the Trent & Mersey Canal in 1954

But Brindley would not live to see much of his legacy; he died at home in September 1772, probably from pneumonia he contracted after a severe rainstorm while surveying a new branch of the Trent & Mersey.

"You cannot overstate the importance of James Brindley's contribution to the industrial revolution," Mr Crowe said.

Regardless of the idiosyncrasies of his designs or his methods, Dr Malcolm Dick, director of the Centre for West Midlands History and an academic from the University of Birmingham, said Brindley's work was "huge" and "pioneering".

"Brindley was an important figure - not the first creator of canals, but someone whose skills were applied to enable commercial and industrial elites to develop new transport routes.

"Clearly someone who we need to associate with the development of Birmingham and the West Midlands."

Historian and Stoke-on-Trent Labour MP Tristram Hunt said: "He was a great ally of Wedgwood. They were good friends and Wedgwood was always worried about how hard Brindley was working because he was a workaholic.

"Brindley's work was enormously important ensuring the Trent & Mersey Canal went through the Potteries and north Staffordshire which was vital in the development of the ceramic industry.

"It made it easier to export to Liverpool and easier to import clay and flint."

Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce's chief executive Paul Faulkner said: "James Brindley's vision for an effective and efficient transport system allowed industries such as manufacturing to grow significantly.

"Birmingham and the Black Country became great economic drivers when the canal network started transporting manufactured goods, raw materials and coal.

"The region remains a hotbed for manufacturing and other industries and we have James Brindley to thank."