Barnsley and Middlesbrough see pupil exclusion rises of 300%

- Published

Joe Salt (right) has been excluded nine times because of behaviour relating to his autism

The number of pupils expelled from schools in some parts of England has risen by more than 300% in three years.

There were 5,800 permanent exclusions in 2014-15 compared with 4,630 three years ago, government figures show, external.

Fixed term or temporary exclusions rose from 267,520 to 302,980 in the same period.

Some councils where large rises have been recorded said the increase reflected a greater willingness to tackle "poor behaviour".

The largest rises were seen in Middlesbrough, Barnsley and North Lincolnshire.

Both Barnsley and Middlesbrough also had the highest exclusion rates, with both having the equivalent of one exclusion for every six pupils last year.

Not only has the number of fixed term exclusions increased, but the average number of days children are excluded for has increased steadily over three years - from 4.18 days in 2012-13, to 4.23 in 2013-14 and 4.38 in 2014-15.

Middlesbrough saw the largest increase in permanent exclusions, up 357% from 750 in 2012-13 to 3,430 in 2014-15.

The council says the rise reflects efforts by head teachers to tackle poor behaviour.

"Exclusions are a measure of last resort when all other avenues have been exhausted, and are designed to change behaviour and improve life chances," a spokesman for Middlesbrough Borough Council said.

"Poor behavioural standards by students damage not only their own chances but the prospects of those around them."

Barnsley saw a rise of 303% and North Lincolnshire 110% during the same period.

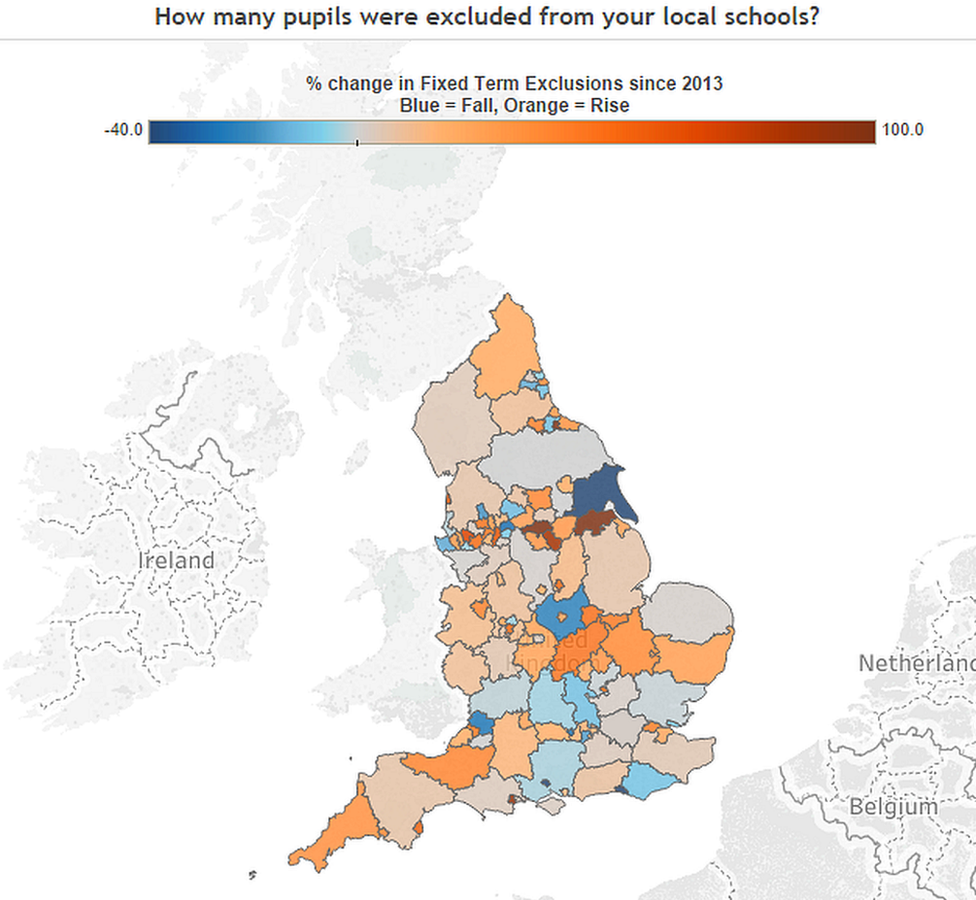

See how many pupils were excluded by schools in your area with our interactive map, external.

Both Teesside and North Lincolnshire have suffered thousands of steel industry job losses in the past two years.

Tony Draper, former president of the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) and current head at Water Hall Primary School in Northamptonshire, said there might be a correlation between particularly high levels of exclusions and wider economic uncertainty in some areas.

"Families in financial difficulty, or with difficult personal circumstances are examples of this, so that could explain the regional variations in the statistics," Mr Draper said.

He also warned school finances were "at breaking point" meaning some measures which might stave off the need for exclusions, such as counselling, support work or clubs, "may be lost".

Alison Ryan, senior policy adviser with the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, said there was a "perfect storm" in some parts of England where long-term unemployment, local authority service cuts, teacher shortages and a lack of available provision for children with special educational needs was severely damaging the prospects of some children.

One parent, from Essex, said bullying against her daughter was "awful" and had taken a huge toll. The perpetrator was excluded.

Persistent disruptive behaviour accounted for the lion's share - 79,590 - of fixed term exclusions, followed by 52,710 for verbal abuse, and 54,370 for assaulting a pupil.

More than 8,000 pupils were excluded for drug and alcohol offences and 2,250 related to sexual misconduct.

Bullying accounts for about 3,000 of fixed term exclusions and 30 permanent exclusions each year.

The impact of exclusions

The biggest increases in fixed term exclusions were recorded in Middlesbrough, Barnsley and North Lincolnshire

The mother of one victim of persistent bullying in Essex said the school's decision to exclude the perpetrator ended up being the only option after all other efforts failed.

The bullying, she said, had been "awful" and had taken a huge toll on her daughter.

Meanwhile, 10-year-old Joe Salt, who has autism, has been excluded nine times - the first time aged four years old and just two weeks into his education.

"It was really sad and lonely," he said.

His mother Zoe said he was excluded by his first mainstream school because "they did not have the staff to cope with his behaviour which was down to his autism".

Ms Ryan said exclusions also had significant consequences on those excluded.

"If you are alienated at school you are more likely to end up not in employment or training and in the justice system at a later stage," she said.

The rise in the past four years follows a period steady decline in the numbers and rate of exclusions before 2012-13.

The Department for Education was approached for comment three weeks ago.

In a statement released on Tuesday, a spokesman said: "Every child should be able to learn without disruption - that's why we've given head teachers more powers to tackle poor behaviour.

"Permanent exclusion is still very rare and should only be used as a last resort.

"We have also announced plans to make schools responsible for securing alternative provision for excluded pupils."

- Published25 July 2013