A hermit's Christmas: Simplicity, solitude and silence

- Published

For many of us, Christmas is a time of hustle and bustle, bright lights, music and over-indulgence. But for Rachel Denton, this Yuletide will be a period of silence and contemplation. Not so different from her everyday life - Sister Rachel is a hermit.

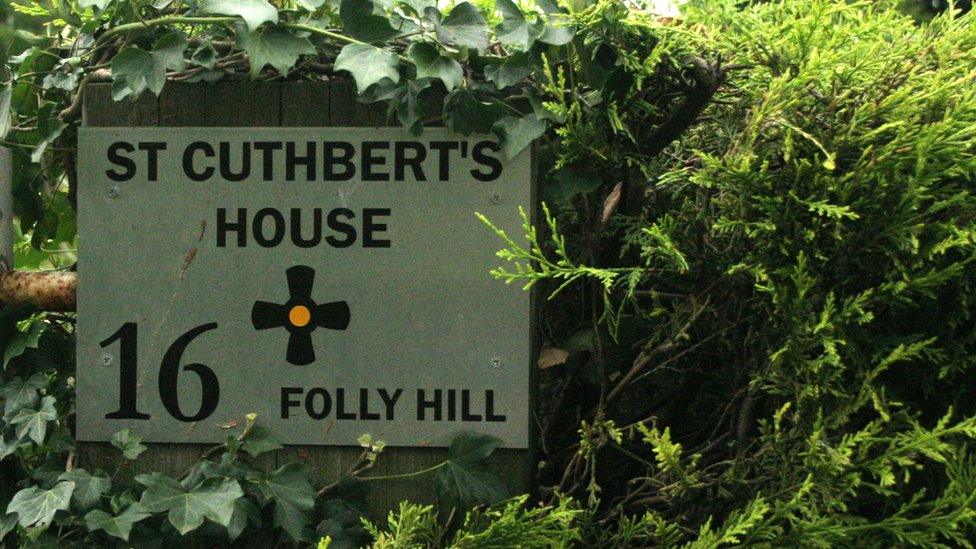

Forget about the notions of unwashed bearded men living in caves. Her hermitage is a modest end-of-terrace house in rural north Lincolnshire, which she shares with her dog, a Chihuahua-cross called Mr Bingley. And although she lives a quiet, simple life, she does occasionally interact with others.

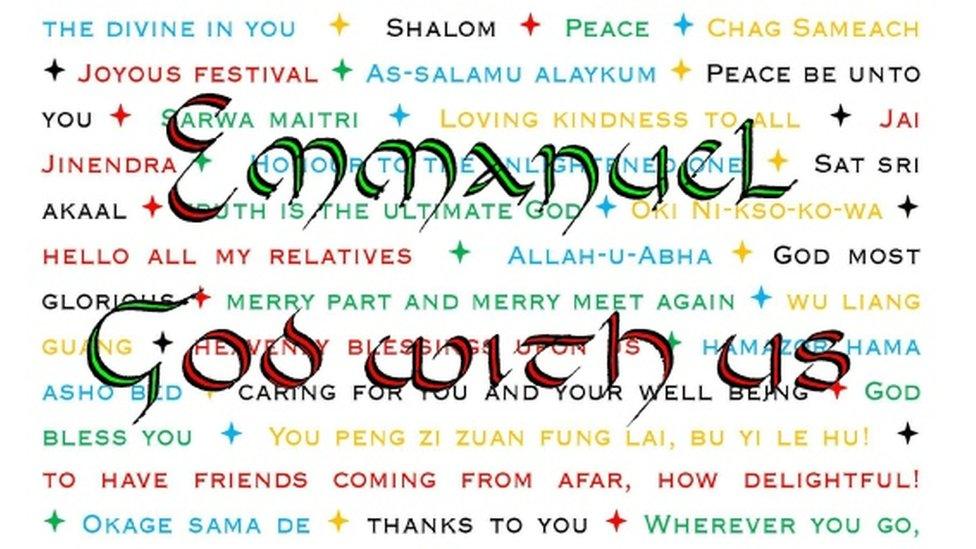

She has a Twitter account, external - the biography reads: "Hermit, scribe, printer - tweets are rare, but precious!" - and a website through which she sells her hand-illuminated greetings cards: "There is not much call for rush mats and rosaries these days - the traditional industries of the hermitage."

She rises early, spends hours at prayer, goes to work, tends her garden, walks.

It's a life of self-restraint many would find difficult, but Sister Rachel doesn't conceal her delight at the way she lives.

"I get up, I go to sleep. I'm grateful for being alive. And that's enough. I'm with God every day.

"I really do have a lovely life. It's wonderful. I really do enjoy myself."

Her weekly treat is a brief lie-in on Sunday mornings when she listens to Radio 4's Something Understood - a music, prose and poetry programme with a spiritual theme, broadcast at 06:05.

Every evening she listens to The Archers. Her face lights up as she discusses the machinations of the nefarious Rob, and she was delighted when Helen was found not guilty of his attempted murder.

When not animated by the goings-on in Ambridge, she exudes a sense of quietude and determination. Or as she puts its: "I'm reclusive and stubborn". But she also laughs a lot.

The desire for solitude may have stemmed from childhood - she was deaf when she was young, before an operation restored her hearing, suddenly introducing noise into her life. One of six children, she was brought up in Stockport, where her father was a university lecturer.

She describes the life of hermitage as "one of becoming ever more sensitive to God-in-this-place. Which might involve appreciating the loveliness of a flower, or the dance of the light through a window, or the still-life of a mundane object suddenly striking in its random beauty. Or more likely, the meticulous job of recycling waste items, or weeding the raspberry canes."

She's keen to point out the practicalities - being a hermit is not a romantic lifestyle.

The most important thing for those wanting to embark on eremitical living is self-sufficiency, she says to people who email her asking for tips.

"You need to be able to support yourself. So you need an income. I always say being a cleaner is a very good job for a hermit, because you generally go to homes when the householders are out.

"Part of me would love to live in a cave on a mountain and see nobody ever and not have a Facebook and Twitter account, but the reality is that if I'm to earn my own living, technology enables me to do that."

Saint Bruno of Cologne was a more traditional hermit

Raised Catholic, she went to university where she "had boyfriends and all of that", and then entered a convent for a year as a Carmelite nun - something her father thought "was a waste" of her academic potential. She enjoyed the silence and solitude - but found she couldn't bear the communal living.

"I had to have a word with God," she says.

"I said 'you might want me to become a nun, but that's not going to happen'.

"So I took God with me. You know, being a hermit is much harder than being a nun. A nun has a built-in community, somewhere to live."

On leaving the convent, she didn't embark on a solitary life straight away. She trained as a teacher, eventually becoming deputy head of a school in Cambridge where she taught maths and science.

Since taking the leap into her new life in 2001, she has been somewhat feeling her way. At first, she didn't wear anything distinctive, but now she dresses in a scapular - a long garment suspended from the shoulders, a bit like a severe pinafore.

She admits, that although she is guided by her rules of life, there are times when she has to make it up as she goes along. As she embarked on her new path, she sought the blessing of the Most Rev Malcolm McMahon, then the Catholic Bishop of Nottingham.

"He said: 'We don't do hermits.' He didn't know anything about it - although he did grow to like having a hermit in the diocese: it gave him kudos with the other bishops."

For those first five years she was "incognito", but following her Solemn Profession in 2006 - an official commitment to life-long hermitage at a special Mass - there has been interest.

Christmas has its own rituals for the hermit.

"On Christmas Eve I always listen to the Festival of Nine Lessons on the radio, then a period of quiet after that.

"The high point is midnight mass at the local church."

The day itself will be spent "quietly at the hermitage [her house]. Preparing Christmas dinner - although on a less epic scale than most people - reading, listening to carols, probably a walk, a DVD in the evening.

"Very relaxed, no timetable."

Advent is a busier time: "I lay out my crib and decorate the hermitage day-by-day."

She also sees God in secular celebrations.

"There is lots of talk about the "true spirit of Christmas" and a sort of regret that we might be losing that. Of course things can get out of hand on the commercial front, but I do think there is room for lots of the 'peripheral' celebrations.

"Father Christmas and the John Lewis Christmas adverts - God is with us in that stuff too."

So does she ever get lonely?

"Never. My brother said he thought I'd not last two years as a hermit - but it's been 15 years and I still love it."

Rachel Denton produces hand-calligraphied greetings cards

Loneliness at Christmas

Sister Rachel enjoys her solitude - but she's in the enviable position of choosing to be alone.

Charities warn an increasing number of people are experiencing isolation. Age UK says there are more than a million people who'll be lonely on Christmas Day. The organisation offers a befriending service, external.

The Mental Health Foundation, external points out that Christmas only accentuates the isolation some feel.

Which? has a list of groups, external that can help alleviate loneliness.

Each year Rachel builds her crib on the mantelpiece throughout advent. The ox and the ass represent the innate wisdom of all of creation

She says her family were fine with her choice, if a bit puzzled. After all, they had "already been through the whole nun thing".

At first she had to be quite firm about putting people off coming to visit her in her former council house near Market Rasen (a home she was able to afford to buy thanks to getting on the property ladder in Cambridge at an opportune time).

They didn't understand she wanted to be alone.

Over the past couple of years, she's been forced to accept more company than she's used to - as she needed treatment for cancer, something she found, she says, "fascinating".

"All the scientific bits of the treatment, I was really interested in.

"What I found hard was not being on my own and having to accept help. And what I couldn't bear is the pain. Pain is a terrible thing, and for some people there's no escape from it."

Cancer didn't shake her faith. If anything, the year she was ill - "lost in the radiological mists of time" - was "almost magical. I could indulge in being silent and alone. God was just there".

"It was interesting when I got cancer because you make a bucket list and my bucket list was to spend my life as a hermit."

How will she mark the end of the year and the beginning of the next? As might be expected - "quietly". New Year's Eve night is spent in prayer vigil, a practice common in many monasteries and convents.

"I like to think of folks partying the night away whilst I am praying for them," she says. And she couldn't be happier.