Torrey Canyon oil spill: The day the sea turned black

- Published

Fifty years ago, the supertanker SS Torrey Canyon hit rocks off the coast of Cornwall, spilling more than 100,000 tonnes of crude oil into the English Channel. Beaches were left knee-deep in sludge and thousands of sea birds were killed in what remains the UK's worst environmental accident.

It was the first major oil spill in British and European waters, causing enormous damage to marine life and the livelihoods of local people. It also led to changes in the way people viewed the environment.

Brittany, in northern France, bore the brunt of the thickest part of the slick, and it became known there as the marée noire, or "black tide".

More than 15,000 sea birds were killed. Clogged up with thick viscous oil, they were washed up both dead and alive on the shores. Future populations of some species took decades to recover.

You might also like to read:

This destruction of the birds had a direct impact on sanitation. Many were scavengers, eating rubbish which washed up on shore. That rubbish was instead left to rot on the beaches.

The deaths of birds and marine mammals in the first days after the spill were only a fraction of the final toll. The effects went on for years, working on organisms from the bottom of the food chain - the plankton and small invertebrates that live in sediments, through mussels and clams on up to fish, birds and mammals.

And the British clean-up effort, which involved the excessive and indiscriminate use of powerful chemicals, made a bad situation much worse.

At the time, the Ministry for Agriculture and Fisheries determined that the holiday industry - and clean beaches - were more important, external than the "very small" amount of damage it anticipated to wildlife.

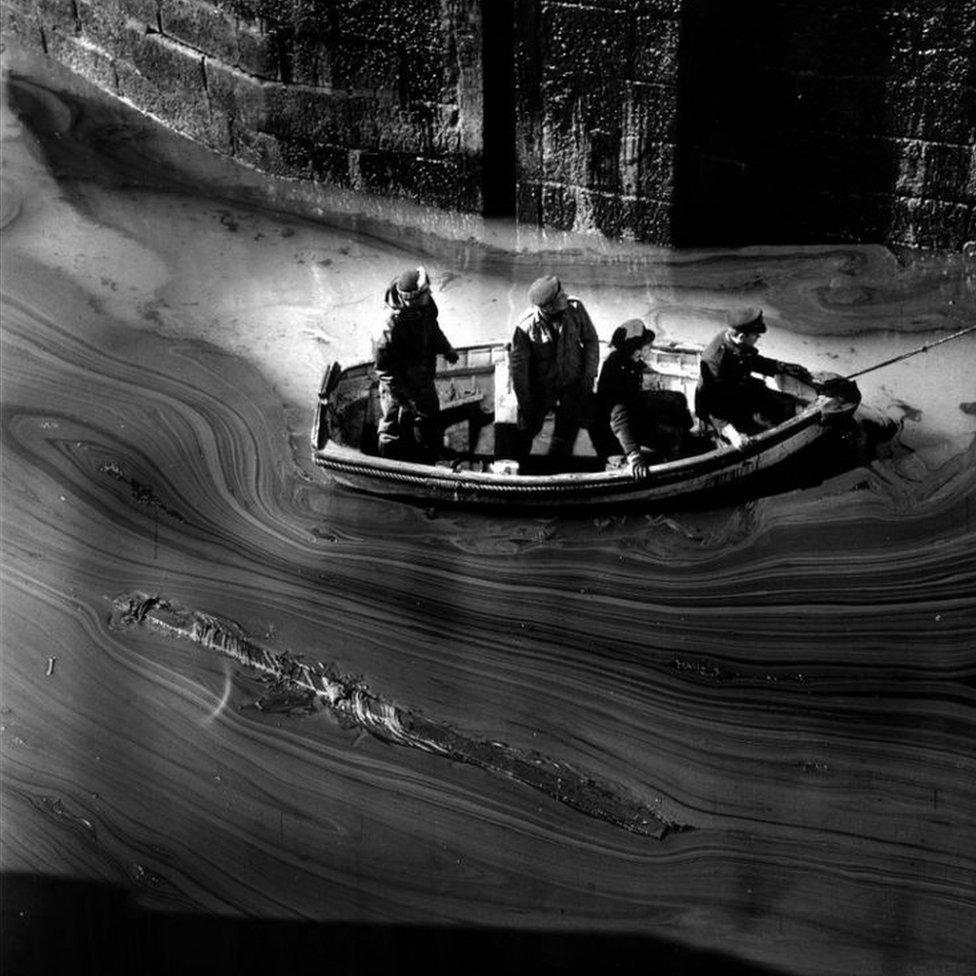

So more than two million gallons of a chemical called BP 1002 was sprayed on to the affected waters. Hoses were squirted over beaches, volunteers used watering cans, fishermen pumped the chemical into the sea from their boats. The Army even punctured holes into barrels of it and rolled them off cliffs.

Torrey Canyon: The shipwrecked supertanker

The plan was for the chemical to break down the oil and allow it to disperse and be removed by natural bacteria. But instead it killed any kind of marine life it came into contact with, from seaweed to limpets to fish.

It pooled on beaches for hours before being washed away by the tide, making the poisonous effects even worse. A Marine Biological Association (MBA) report in 1968 said, external the UK's use of detergents resulted "in the death of a large number of shore organisms of many kinds".

It took 13-15 years for the treated areas to recover, about five times longer than those areas where the oil was dispersed naturally by wind and waves.

Professor Martin Attrill, director of the Marine Institute in Plymouth, said the British response to the crisis illustrates how different attitudes to the environment were then.

"At the time the Torrey Canyon went down we were still considering the sea as the main place to put all our waste," he said.

"We've had a change in mindset. At the time it was 'the environment can deal with this' and the main concern was for the ship and whether it could be salvaged.

"Then people started to wake up - not just to the environment, but to the fact it reduced tourism. People didn't want to visit areas where there'd been an oil spill, there was an inability to sell goods, the brand was tarnished. Now we know about the benefits of clean seas."

On the affected section of the Breton coast, breeding pairs had returned from their migration to nest when the disaster happened. The Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux , externalcalculated that there were 450 pairs of razorbills before the spill but only 50 after. For guillemots the number of pairs fell from 270 to 50.

About 85% of puffins on the French coast were also killed, the RSPB estimated. Because of their low reproductive rate, it took several decades for the population to recover.

Thousands of sea birds died, some from being in contact with the oil and others from chemical burns from the detergent

Julian May was an 11-year-old boy on holiday in Cornwall when the disaster struck. He remembers the surf being like "brown, frothy coffee".

"On the beach itself there were thick clags of oil, great lumps of it," he said. "It was spreading all over the place.

"More than anything, I remember the smell - the strange smell - of this oil."

Dr Gerald Boalch was a senior scientist aboard an MBA ship which took samples shortly after the spill.

"On British beaches where the detergents were used, many animals and plants were killed," he said. "Spraying the detergents was definitely the wrong thing to do.

"It broke up the oil, which helped the tourism industry for the affected places, but the oil sank from the top of the waves to the bottom, breaking into smaller parts and being ingested by marine life."

In Cornwall, former biology teacher Richard Pearce from Treburrick has studied Porth Mear beach three times a year since the Torrey Canyon's murky load came ashore.

He said it took about five years for the environment to even "stabilise". Before that, he said, the beach was "barren".

Volunteers use watering cans full of dispersal agents try to get rid of the oil on the beach at Marazion, Cornwall

So how had this disaster happened?

The Torrey Canyon had been en route from Kuwait to Milford Haven, in Pembrokeshire, on the morning of 18 March 1967 when its captain took a shortcut and hit Pollard's Rock - a reef between Land's End and the Isles of Scilly.

Every drop of the crude oil borne by the ship seeped into the Atlantic.

By evening an eight-mile slick had seeped from her ripped hull. The following day it was 20 miles long. It eventually bled into a 270 sq m (700 km2) foul-smelling smear.

After failed attempts to shift the tanker off the rocks, the crew were rescued by lifeboats.

Then the British government ordered the marooned tanker be bombed, both to burn off the remaining oil and to scuttle the vessel.

Over two days, 62,000 lbs of explosives were dropped on the stricken craft and surrounding waters, along with 5,200 gallons of petrol, 11 high-powered rockets and napalm.

The smoke from the bombed tanker could be viewed for miles

Of the 42 bombs aimed at the target, about a quarter missed. Others did not explode. And while some of the oil burned, waves kept extinguishing the flames.

John Eatwell, who took part in the bombing missions, said his abiding memory was of the "overpowering smell of oil, which penetrated the cockpit even at several thousand feet above the slick".

"The column of smoke from the burning oil went up to about 20,000 ft. To continue bombing we had to dive into smoke and flame," he said.

The Torrey Canyon broke in two and finally sank 12 days after it ran aground.

The approach in France was perhaps less scientific, but much kinder to nature.

The French let the oil come ashore and then scooped it up. On their rocky beaches, the oil that remained gradually weathered and the marine life was not as badly affected.

French soldiers were brought in to clean up the slick on the beach at Perros-Guirec

Meanwhile on Guernsey, the oil hit the shore seven days after the Torrey Canyon finally sank.

The island was heavily dependent on tourism and officials were keen to clear the beaches as quickly as possible. The chosen solution was to suck the oil into sewage tankers, transport it to a disused quarry and dump it there.

Years later, micro-organisms were introduced in the hope they would convert the oil over time into water and carbon dioxide. However, this had limited success.

"I don't think they'd have ever imagined that 50 years later the oil would still be there," said Rob Roussel, who oversees the quarry for the Guernsey government.

"At the time there was no awareness about how to deal with it, and the over-riding concern was the economy, so it was all about clearing the beaches as quickly as possible.

"We would have expected that the oil would have all been released by now but it continues to appear."

Some of the oil which reached Guernsey was sucked into lorries and dumped into a quarry (pictured in 2010). The surface now, in 2017, is much clearer

The Torrey Canyon disaster did have some positive consequences, including the creation of maritime regulations on pollution.

A young David Bellamy, at the time an environmental consultant, was asked to comment on the disaster - and his unique style led to a career in television.

Speaking 50 years later, he said: "The Torrey Canyon Disaster was a milestone in the environmental world.

"It was a tragedy that [it] had to happen before the public became focussed on potential loss of natural life, in this case marine.

"The media images of pollution and the attendant wildlife disasters made people begin to become involved in this new ethical conservation.

"It also became apparent that life is more resilient than anybody thought. In general if an oil spill is contained, the marine flora and flora will eventually return."

The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation (ITOPF) was set up in direct response to the Torrey Canyon disaster. It now provides emergency responses to spills across the world.

Single hull oil tankers - where one hole could lead to a catastrophic leak - were phased out and replaced with double hulls, which offered more protection.

The American owners of the Torrey Canyon eventually paid £3m compensation to the British government. The accident remains the worst - and most expensive - in UK waters.

As for the Torrey Canyon herself, she still rests at the bottom of the ocean. The tanker which destroyed so much is now - somewhat ironically - a haven for marine life.

Additional reporting by Chris Quevatre

- Published17 November 2010