Why don't we elect MPs by proportional representation?

- Published

Should the UK start to use a new system to elect MPs at Westminster?

As the general election approaches, BBC News looks at why MPs are elected by the first-past-the-post system and not proportional representation.

Reader Anthea Beszant was among those who asked about the voting system using this form for questions about the election, on 8 June.

"As a 70+ age citizen of this country and having always voted I have never been directly represented in my entire life," she said.

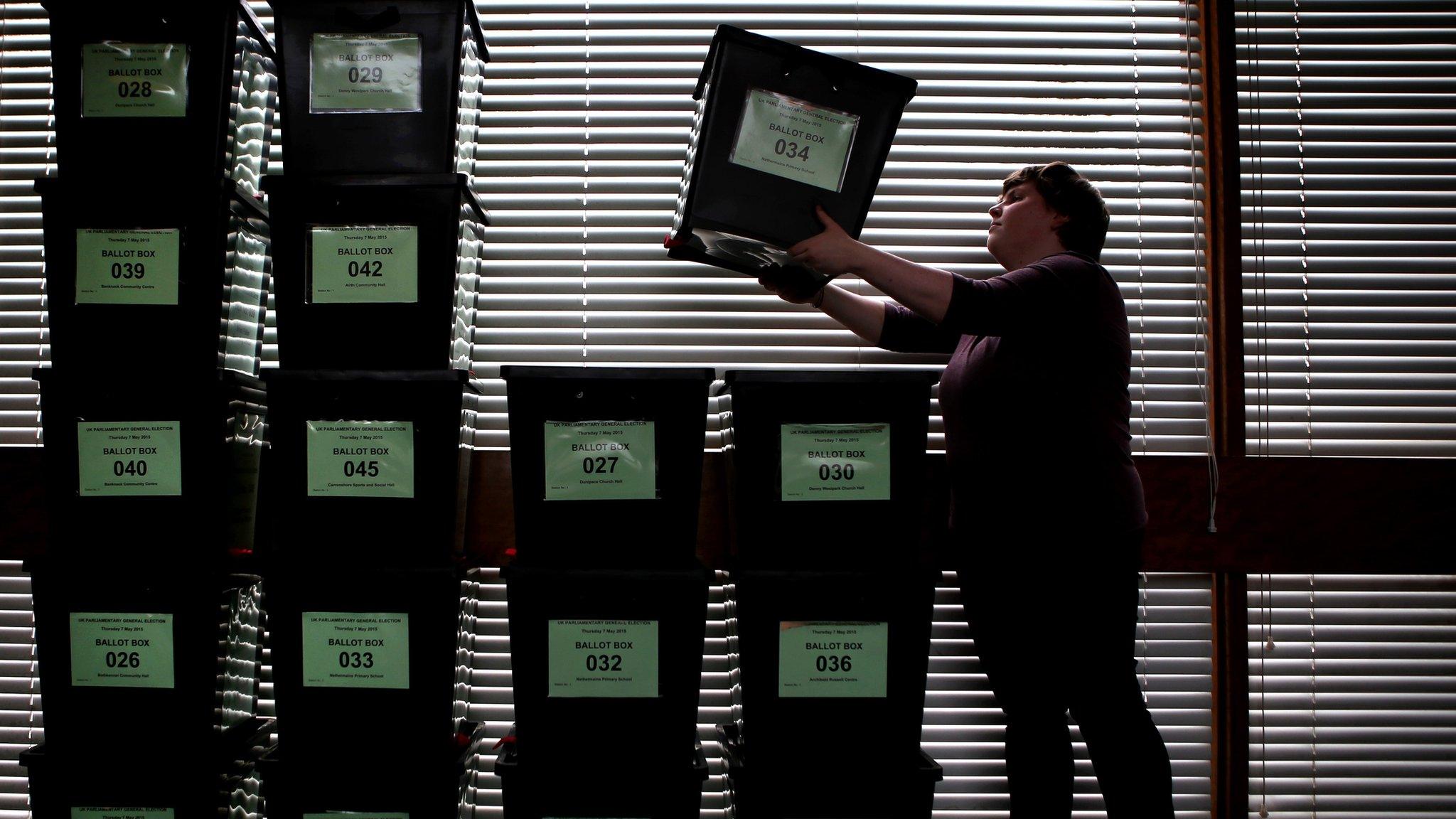

Currently under first past the post (FPTP), the candidate who receives the most votes in a local constituency wins a seat in the House of Commons.

This means the number of seats each political party wins does not reflect its share of the vote nationally.

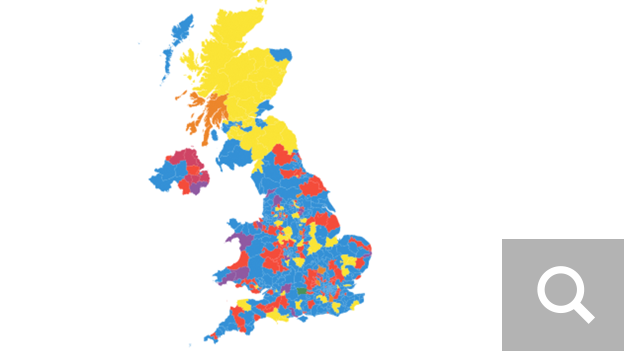

How did your constituency vote in 2015?

Sorry, your browser cannot display this content.

As to whether the public has an appetite to see the voting system change, a previous test of opinion in 2011 reflected the "public's attachment to FPTP", says Dr Matt Cole, teaching fellow in History at the University of Birmingham.

"England has almost always voted by giving the seat to the person with the largest single number of votes," he said.

"That's because our system has evolved from a time before mass party politics.

"It was designed to choose community representatives - that's why it's called the House of Commons.

"The most popular members of those communities were individuals representing key interests in their constituencies."

Electoral reforms throughout history changed things like the number of MPs and constituencies but the FPTP System has remained unchanged, he said.

What about proportional representation (PR)?

PR is the idea that parties' seats in parliament should be allocated so that they are in proportion to the number of votes cast.

At the 2015 general election, UKIP picked up nearly four million votes nationally, which would have given the party dozens of seats under PR.

However, under FPTP, it won only a single seat which was in Clacton.

Some 331 of 650 MPs elected in 2015 won their seat with less than half of the vote in their constituencies.

The House of Commons is so named because throughout history seats were given to members of the community

Katie Ghose, from the Electoral Reform Society (ERS) which campaigns to change the way we vote, said Ms Beszant was not alone in her view.

"Millions of voters feel they are unrepresented in parliament - whether it is because they live in one of hundreds of 'safe seats' across the country, or because they feel forced to 'hold their nose' and opt for a 'lesser evil' rather than the party they truly support."

Daniel Mahoney, from think-tank the Centre for Policy Studies, said there were "key arguments" in favour of the FPTP system.

"Power can change hands from one government to another quickly and effectively," said Mr Mahoney.

"It also means that members of parliament - including government ministers - have a direct link to a constituency."

Ms Ghose said the ERS had "seen our support surge in recent years".

She said: "After 100,000 signed the petition for fair votes earlier this year, pressure is mounting for real reform.

"We are confident that it's not a matter of if, but when."

Mr Mahoney said the FPTP system had "served British democracy well and is likely to continue to do so".

He added: "The British public voted overwhelmingly to keep the current voting system and the result should be respected."

The AV referendum

In that 2011 test of public opinion, voters were given a referendum on whether to change the system to the alternative vote (AV).

Under AV, voters rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate is the first choice of more than 50% of voters, second, third and fourth preferences are distributed until one candidate has a majority.

Holding the referendum was part of the agreement between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats when they formed a coalition government.

The result was a resounding "no" from more than two thirds of people.

The ERS, which saw it as a step towards "fairer votes", said though it was "not proportional representation, external".

- Published15 May 2017

- Published10 May 2017

- Published9 May 2015