Faggots and groaty dick: Why some foods travel and others don't

- Published

Tucking into the foods of our childhood can conjure up fond memories of home. But while some regional delicacies remain firmly local, others travel to other parts of the country or even the world.

Mary-Ellen Johnson recalls the warmth of her favourite winter meal - a rectangle of steamed suet pastry encasing squares of fatless smoked bacon and slices of onion.

As one of eight children her family was "very poor" but "fed well" by her mother, who often turned to the Sussex bacon and onion pudding.

"The foods of childhood remind me of being home with mum and my many siblings and it brings back many good memories," said Ms Johnson, who grew up in Hove.

"I'm now gluten-free and I really miss eating this with mashed potatoes, green vegetables and onion gravy."

According to the 64-year-old, none of her neighbours in Essex where she lives now have ever heard of the dish.

Nor has she ever encountered it on her travels around England.

Lucy Stableford-Grieve's bacon and onion roly poly is baked, not steamed

But blogger Lucy Stableford-Grieve has been using the same ingredients in Kent, to make what she calls a bacon and onion roly poly.

"My mum and dad remember it as one of their favourite school dinners in the late fifties and early sixties," said the 37-year-old.

"I was looking through my mum's old recipe books and found the traditional steaming method.

"I muddled through and adapted it for the oven and now I make it for my kids and they love it."

Similar recipes like Berkshire bacon pudding, external and Romany bacon pudding, external can be found around England - so how have they travelled to other parts of the country?

You might also like

Cookery historian, professor Roland Rotherham, said the steamed or boiled pudding can be traced back to Roman times.

It was easy to cook, tasty, and required minimal amounts of water, which was collected from wells and brooks then boiled.

The fact it was later adopted by the Anglo Saxons is typical of the fact that people take their favourite dishes with them when they move to pastures new.

"These are the tastes we travel with and introduce to where we settle," he said, which could explain why variations of them pop up across the country.

The humble savoury pancake is elevated by its fillings - favourites include cheese, bacon and sausage

The Staffordshire oatcake is a prime example - not only has it crossed county lines, homesick expats made headlines when they started cooking them up in the United States.

There's a reason for that, says Stoke-on-Trent resident Michael Collins - they're "food from the gods".

His love for the savoury pancake started 60 years ago, when he would roll it up and dip it in bacon fat for breakfast.

"It tasted lovely," he said nostalgically. "Almost better than the bacon itself."

Food writer Xanthe Clay described the humble foodstuff - made from oatmeal, flour and yeast - as a "a wonderful thing".

"Who needs sissy tortillas or burritos or wraps when you can have a proper sustaining Staffordshire oatcake?

"[It] can be filled with cheese or whatever you like, and eaten hot or cold... plus they are full of lovely slow-burning carbs, and delicious too."

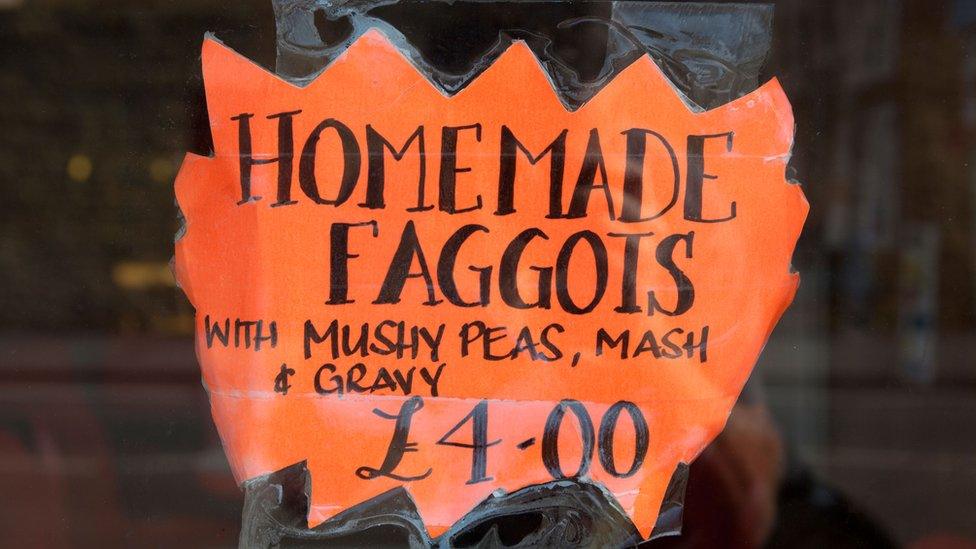

According to Prof Rotherham, faggots gets its first mention in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1851

Nearby, in the West Midlands, a meatball made of pig offal encased in part of the animal's stomach is a regular sight on the region's menus.

But despite being an "archetypal Black Country food" it's not to everyone's tastes, said David Cowing, from Sutton Coldfield.

"I came from the Lake District in 1972 and I remember being introduced to faggots by a local and absolutely loving them for their rich flavour.

"For years I had no idea what the ingredients were. We had them every year for about 10 years at a school summer camp I was involved in.

"Not all the kids were as keen to eat them as me so there were always extra helpings."

Chef Glynn Purnell said he was a "big advocate" of faggots and peas

Michelin starred chef Glynn Purnell is a "big advocate" of the divisive dish.

He said the recent surge in "nose-to-tail" eating - a movement which looks to cook the whole animal rather than focus on choice cuts - has seen faggots popping up at eateries across the UK.

"It is estimated that tens of millions of faggots are eaten every year, so they can't be that unpopular," he reasoned.

The foodie, from Solihull, gave faggots their five minutes of fame when he served a twist on the meal - which is often served with mash and peas - on BBC Two's Great British Menu.

"What can be quite scary is the thought of a lung, heart and kidney staring at you - it's enough to make any meat eater a veggie.

"But faggots turn that ... into a delicious, rich, moist, sophisticated piece of cooking.

"The strong flavour of offal and unusual, challenging textures can be a delight to the culinary adventurer."

Groaty dick - sometimes known as groaty pudding - is something of an acquired taste

A dish that has not quite made the leap on to the nation's plate is the oddly named groaty dick.

Prof Rotherham said it may have originally arrived with Welsh "navvies digging out the cuttings for the canal systems".

But the thick meat porridge - sometimes known as groaty pudding - found its way to the Black Country, where it is still made at the Black Country Living Museum's bonfire night.

Made from oat husks, leeks, onions stock and cheap cuts of beef, its appeal once lay in the fact it was "calorie heavy, cheap to make and could be left on the range for hours while out at work or looking after children," said curator Grant Bird.

The dish's stodgy structure also made it a portable meal for the working classes, said chef Keith Floyd, who visited the area in 1988 to learn how to make the traditional recipe, external.

"In the olden days they'd cook this so thick, let it get cold, then cut it like a cake...the man would take a slice of this in his satchel to work and munch on it."

But the quality of the ingredients and general appearance has meant that unlike faggots, it has not been hailed a culinary delight further afield.

"Today it's seen as quite low grade food," said Mr Bird, diplomatically.

"From a flavour profile it's not brilliant and it looks horrible."

Chef Keith Floyd visited the West Midlands in 1988 to learn how to make groaty dick

So is the movement of recipes from one place to another simply a matter of taste?

Not so, says Prof Rotherham.

"The reason that many recipes remained regional is down to the fact that many people did not travel, even after the Industrial Revolution.

"The recipes stayed within certain boundaries. Those that did travel brought the food with them."

But Ms Clay believes that could be about to change because we are in the midst of a regional delicacy resurgence.

"I think we are becoming even more interested in local foods because of gastro-tourism.

"People travel to places because of the food we can't eat anywhere else and that's brilliant.

"The more we explore these dishes the more we will be going through old recipes and bringing up old memories."

Who knows what might end up on our plate next.

This story was inspired by questions from readers of the BBC News website.

- Published22 April 2017