Dripping, apples and milk: Making curry the Victorian way

- Published

A Victorian curry recipe featuring sour apples and dripping has surfaced in East Yorkshire. It is one of the more extreme examples of how Indian cuisine has evolved in British hands.

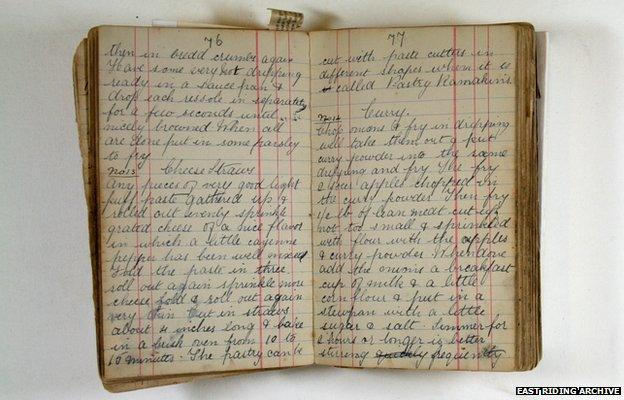

On page 77 of a notebook belonging to a domestic servant from East Yorkshire, there is a recipe for curry.

Eleanor Grantham's Victorian version of Indian cuisine combines half a pound of meat, two sour apples and a cup of milk with unspecified amounts of dripping, onions and curry powder.

But while its ingredients are unlikely to get mouths watering in the way a modern Madras might, it was good enough to grace the dinner table of Manor House in Willerby in 1890.

"The earliest British recipe for curry was 1747, which is a lot earlier than this recipe, but as far as the region is concerned, it's the earliest recipe we've found," said Sam Bartle, collections officer at the East Riding Archive where the recipe was discovered.

"I'm told the Victorians were quite keen on curry - it was the height of the British Empire so there were interactions with places like India, so it's not surprising."

.jpg)

The recipe is the earliest indicator historians have found of eating curry in the East Riding

The hard-backed book was unearthed by a descendant of Ms Grantham, who recorded the recipes gathered during the course of her service.

Though the curry's simplicity meant it could have been cooked by anyone, the cost of the spices 125 years ago meant it was reserved mainly for the rich.

David Leaf, catering lecturer at East Riding College in Beverley, said: "In authentic Indian restaurants they would use a teaspoon of coriander, turmeric, ginger, paprika, etc.

"Curry powder is probably an English product, because we didn't have all those spices in those days, because they were expensive of course.

"[This] is a modern British version of a curry, using an amalgamated mixture of all those spices."

A curry is essentially nothing more than a stew, Mr Leaf explained, a method of slow cooking in juices or sauce, or in this case, milk - a regular feature in Indian cooking.

"It's a very simple recipe," he said. "I would think it would make an edible curry by English standards, but not by traditional, authentic Indian methods.

"Have a go."

No stranger to the stove, I accepted the challenge.

I estimated how much onion to use in the absence of exact measurements

There was a time when cooking in animal fat was the norm, with 'mucky fat sandwiches' a staple part of the British diet. But at a time where saturated fat is practically considered a sin, watching a wedge of dripping coat the base of my pan felt inherently wrong.

As it sizzled away, I turned my attention to the rest of the ingredients. It was common for Victorian recipes to lack detail due to dishes being passed on by word-of-mouth and Ms Grantham's recipe was no exception.

The only quantities specified were for the meat and apples, so I used my judgement and allowed a pair of chopped onions to sweat in the grease for 10 minutes before removing and frying a pile of curry powder.

Chunks of apple from two Granny Smiths joined the yellow sludge, followed by half a pound of diced lamb and a sprinkling of flour.

The recipe called for curry powder, dripping, apples, onions and meat

The panel of taste-testers said the apples gave the curry a sweet taste

Milk and yoghurt were typical ingredients in early curries

I was not convinced I was whipping up a culinary feast and my opinion did not improve when I added 200ml of milk and a dash of sugar and salt.

After two hours on the hob, the meat was tender and the apple chunks had become an aromatic jus, but there was no denying its appearance was distinctly unappealing.

A panel of brave work colleagues brandished their forks in the name of journalism with mixed feedback. The main complaints were that it was too sweet for some and too mild for most, but the overall conclusion was that, while it wouldn't be anyone's first choice, it was perfectly edible.

Eleanor Grantham's Victorian curry

The recipe belonged to domestic servant Eleanor Grantham from Skidby, East Yorkshire

Chop onions and fry in dripping well

Take them out and put curry powder into the same dripping and fry

Then fry the two sour apples chopped in the curry powder

Then fry ½ lb of lean meat - cut up not too small and sprinkled with flour with the apples and curry powder

When done add the onions, a breakfast cup of milk and a little cornflour and put in a stew pan with a little sugar and salt

Simmer for 2 hours or longer is better, stirring frequently

Mohammed Aslam, head chef at Yorkshire-based Indian restaurant chain, Aagrah, said Ms Grantham's recipe is an example of how a traditional Indian curry has evolved over time.

"Lamb and apples is one of the oldest recipes," he said. "It's a southern [Indian] style of cooking, because what they do in the south is seasonal - what they grow, they use, like apples.

"At that time, it would be classed as a modern recipe, but not authentically Indian. The dripping is unusual. There's no dripping on the subcontinent, so that's the influence of British cooking.

"In olden days we would use mustard oil or ghee as it's common in the villages to have a cow. In the East Riding, maybe not."

Curry in English hands

An English cookbook, The Forme of Cury, was published in the 1390s

The first curry recipe in English was published by Hannah Glasse in 1747. 'To Make a Currey the India Way' was a stew of chicken or rabbits, with a spoonful of rice and several spices

In Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, published in 1861, a recipe for curry sauce called for butter, onion, curry powder and slices of salted tomato

Kedgeree, or 'Kichiri', comes from an old Indian peasant dish made of rice and lentils. It was picked up in Britain in the 19th Century and turned into a breakfast dish, served with fish and sliced eggs

The korma originated in Persia where the meat was marinated in yoghurt. The British picked it up from India and toned it down to the mildest curry on modern menus

Coronation chicken was created for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Comprising chicken, raisins, curry and mayonnaise, it is seen as a typical Anglo-Indian dish

The Balti is thought to have originated in Birmingham during the late 1970s. Chefs are credited with creating the dish to suit western tastes

The upper classes regularly dined on curry in the 1600s, said Dr Lizzie Collingham, author of Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, but strong flavours fell out of favour in the late 17th Century when French cuisine became popular.

It was not until the late 18th Century when Britain took control of Bengal that Indian cooking came back into fashion and by 1809 London's first curry house had opened.

While The Hindostanee Coffee House did not last long, curry was appearing in Victorian recipe books, including Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management published in 1861.

But by the time the kitchen moved out of the basement and into the main part of the house at the turn of the 20th Century, curry was again culled from the dinner menu due to the smell.

"It was no longer seen as nice for middle class women to cook curry and the British started eating bland food," Dr Collingham said. "Then, in the 1940s, Bangladeshi sailors on steam boats jumped ship and started buying up old fish and chip shops and set up little restaurants and cafes to serve their own communities.

"In the 1960s, there was a large immigration of people from India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, and that's when [curry] started coming back in a big way."

According to National Curry Week, 23 million people eat the dish on a regular basis, with 18% of the UK's population eating Indian food at least once a week.

Peter Grove, founder of the event, said new figures showed people are turning their nose up at the humble Chicken Tikka Masala for hotter and regional dishes.

"Tikka Masala has been number one for many years and was described as Britain's national dish because it is a British/Bangladeshi creation, not authentically Indian," he said.

"The gradual move to hotter dishes is inevitable, firstly because people are experimenting more but more because of popularity of curry as a whole."

But the food being served in our restaurants bears little resemblance to its origins, warned Dr Collingham.

"A peasant would eat rice and dhal, with chillies and onions. What we have in Indian restaurants was invented for the British or adapted for them," she explained.

"But it's completely normal, it's what's been happening to Indian food for centuries. It's a product of the British relationship with India.

"That's what happens when people travel and conquer each other's countries and eat each other's food."

- Published19 June 2012