Smarties: How the stocking staple got its name

- Published

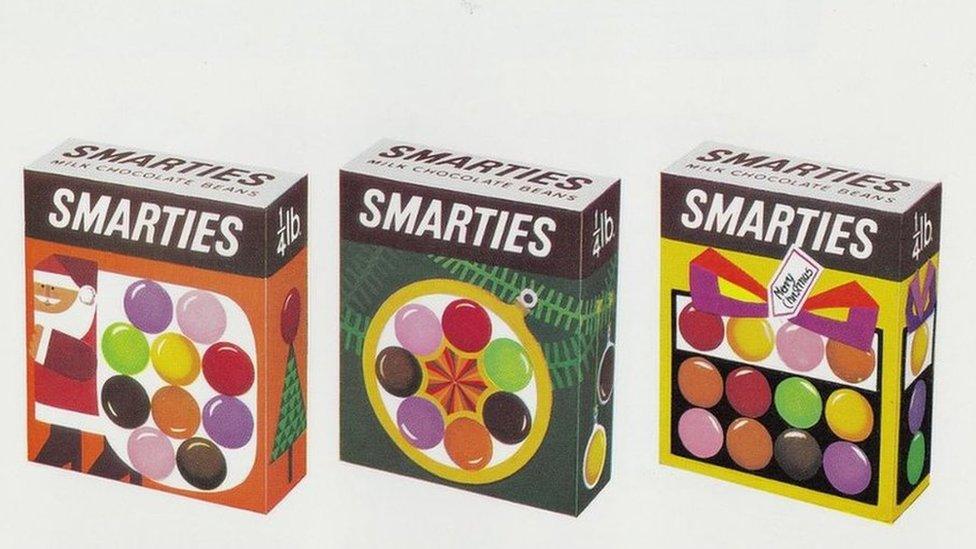

Smarties have appeared in many novelty guises over the years, including Christmas-themed boxes

It's been 80 years since the humble chocolate bean was given a snappy new name. But the Smarties we know and love started out as the butt of an unsavoury joke dreamed up by mischievous confectioners.

If you opened your stocking on Christmas Day to find Nestlé's most popular chocolate sweet among the toiletries, toys and tangerines, it's not surprising.

But as you crunch them slowly one by one - or more likely, tip them into your mouth straight from the tube - have you ever wondered how they got their name?

The history is far more complex than you might imagine.

H.I. Rowntree & Co., which was taken over by Nestlé in 1988, had produced the sweet in some form since 1882, making it the oldest chocolate in its repertoire.

The firm had started to adopt new techniques in sugar-coating honed by its Gallic neighbours, and was one of the first confectioners in England to do so at its factory in York.

But the chocolate drop's origins stretch back even further than the Victoria era, says food historian, Ivan Day.

The chocolate bean originally came in four flavours - milk, plain, coffee and orange

"Smarties belong to a family of confectionery which first appeared in the late Middle Ages in Europe, where various nuts and seeds like fennel, caraway and almonds were coated in sugar," he said.

"They were called comfits - from the Italian word confetti - and were thrown over the bride's head hundreds of years before paper confetti replaced them.

"But in England, from at least the 15th Century onwards, comfits were consumed by the elite social classes to aid digestion and were washed down with a spiced wine - a bit like a medieval Rennie.

"Then during the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, chocolate became a much more important item in confectioners' shops and various chocolate sweets appeared on the scene.

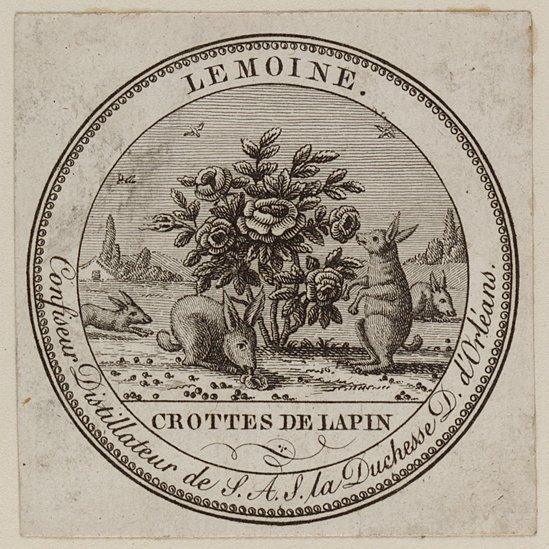

"One was the Crotte de Lapin - a joke sweet made by French confectioners to resemble rabbit droppings."

The Smarties' ancestor was a joke sweet that resembled rabbit droppings

Though popular among the upper classes, there was a downside to this luxurious treat aside from the unappetising name.

The chocolate drops were much richer in cocoa butter than modern chocolate and would melt almost immediately on contact, said Nestlé's archivist, Alex Hutchinson.

"The problem with Crottes de Lapin was that in the early 18th Century, they were being eaten by wealthy ladies who wore expensive white gloves.

"So confectioners had to start covering the chocolate with sugar to stop it melting on their fingers."

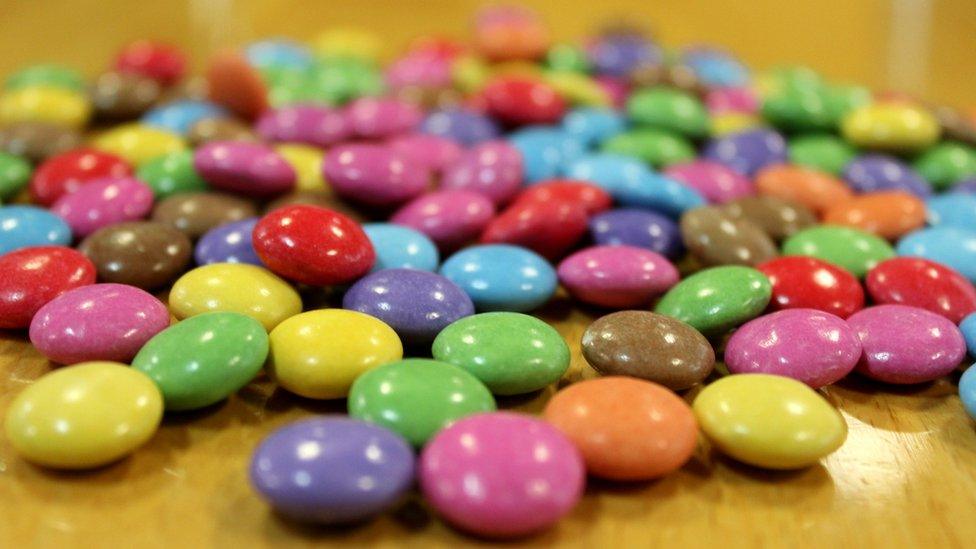

Smarties are a form of dragee - a sweet covered in a hard, sugar shell

In France and Italy, confectioners started rolling chocolate drops in hundreds and thousands, producing a sweet known as a diavolino, or "little devil".

Then in the late 19th Century, a new process called panning gave birth to a sweet covered in a sugar shell called a dragée - pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable and a soft g.

It would be one of the most important changes in the history of the confectionery industry, said Mr Day.

"Panning required a machine rather like a cement mixer to coat chocolate drops with a syrup made from sugar and water that hardened to a shell.

"These sugar-coated chocolate drops were prototypes for the Smartie, M&M and Malteser, producing a Crottes de Lapin that melted in the mouth and not in the hand," he explained.

The popularity of Smarties was a complete surprise to the confectioner

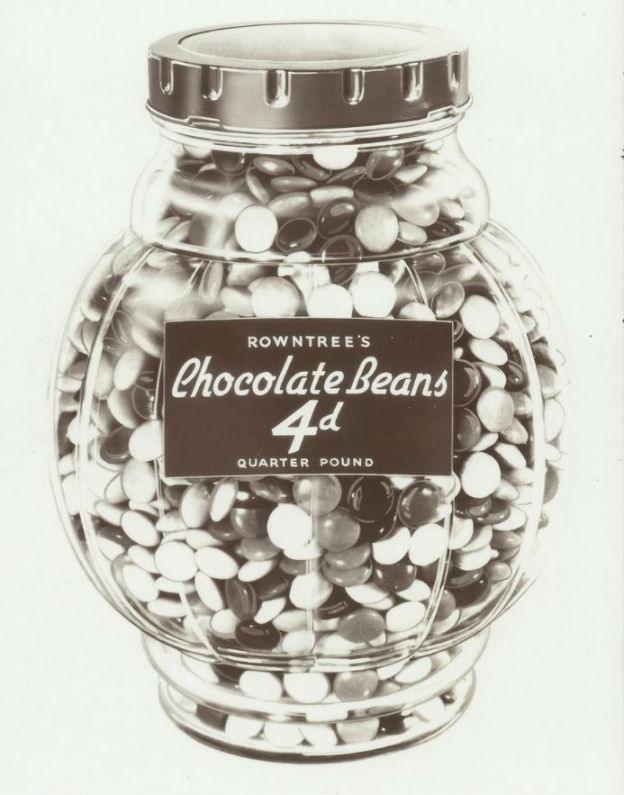

Rowntree's had been making a Crottes de Lapin-style sweet for a number of years; a shell-less drop the same shape as a Smartie that had been selling well in confectioners' shops under the name Chocolate Nibs.

But the turning point in its production came when a French confectioner called Claude Gaget turned up at the Rowntree factory in York in 1879, said Miss Hutchinson.

"Gaget changed the business - [Rowntree's] had been dabbling in making confectionery but it was a very skilled process and we were very lucky he came along.

"He was selling pastilles and asked Joseph Rowntree if he wanted to buy any. And he said, 'no, I want to buy you'.

"From the records we have, Gaget made dragées intermittently from leftovers from chocolate products and they were being sold in grocers' shops, where it seems they were very popular.

"But because we were in Yorkshire, they couldn't say dragée, so we called a spade a spade and called them Chocolate Beans.

"And that's the first record of us making them."

It is unclear why Nestlé's George Harris chose the name

For the next 50 years, the company had modest success with its Smartie prototype, which had been selling well in Marks & Spencer.

But a pivotal moment in the sweet's history came soon after the firm's marketing director George Harris returned from the United States, where he had been inspired by the way American confectioners were creating brands for products.

"Until that point our chocolates were named after royalty - Queen's Chocolate, Emperor's Chocolate, etc. But Harris wanted to give things a personality," said Miss Hutchinson.

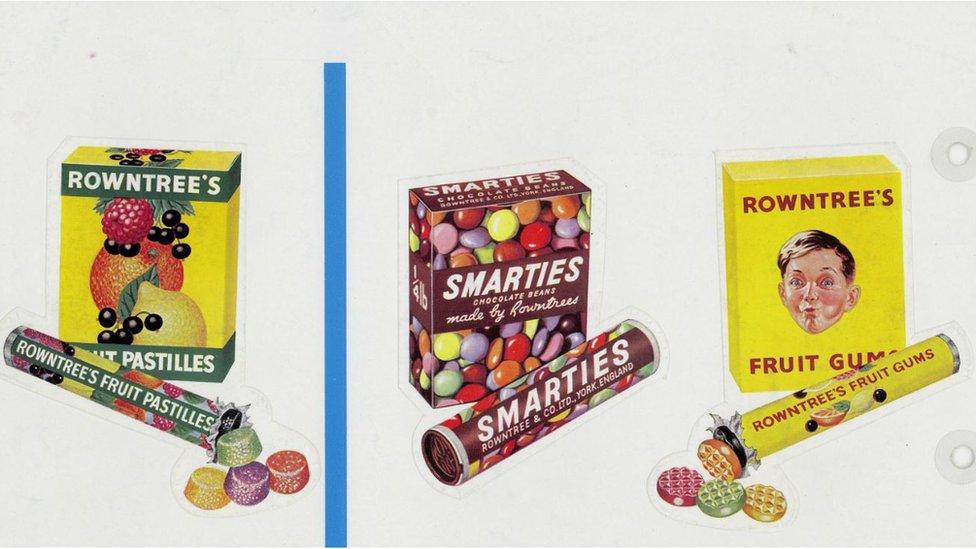

"He gave our old products new names - Rowntree's Clear Gums became Fruit Gums, Aerated Chocolate became Aero, Chocolate Crisp became KitKat."

According to board minutes, the marketing manager wanted to give their sweets "personality"

Crucially, in 1937, Harris turned his attention to renaming the Chocolate Bean to make them more recognisable and the Smarties brand was born.

Its origins however, remain a mystery.

"We're still not sure where the name came from," said the archivist.

"The board minutes talk about all kinds of things to do with the technical aspects, but nowhere does it say 'the reason we're calling it Smarties is…'

"It's tantalising. I don't think we can know what was in his mind but there's something about the rattle when you shake a tube that is a bit onomatopoeic, where it sounds like the word."

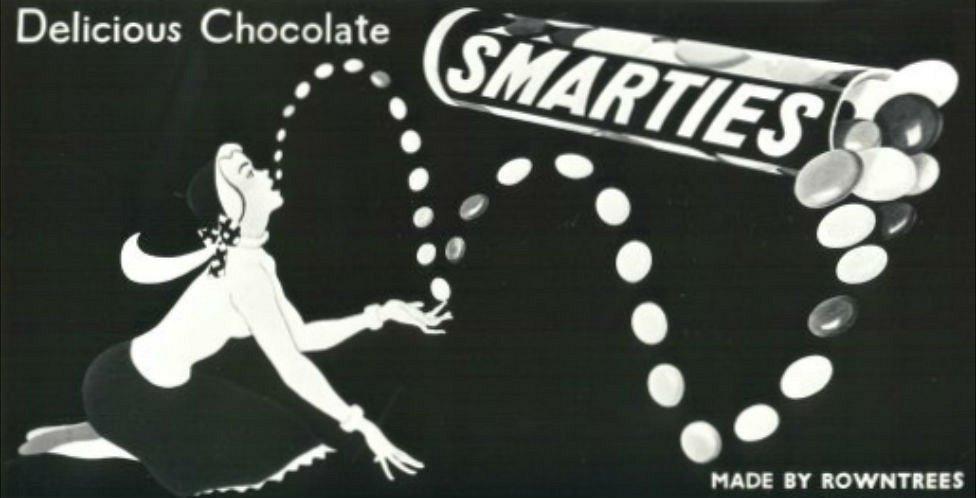

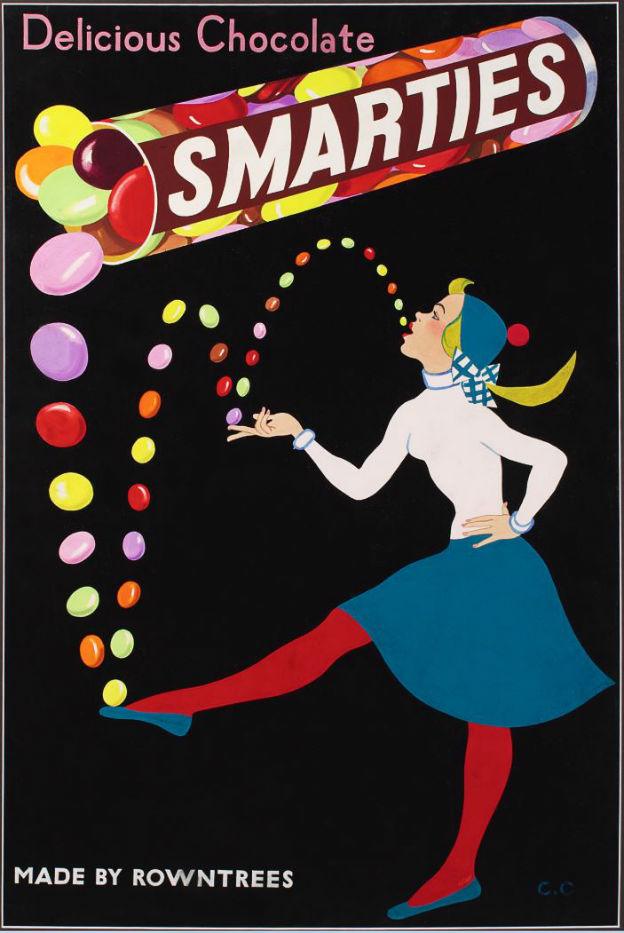

After the war there were numerous campaigns to raise the brand's profile

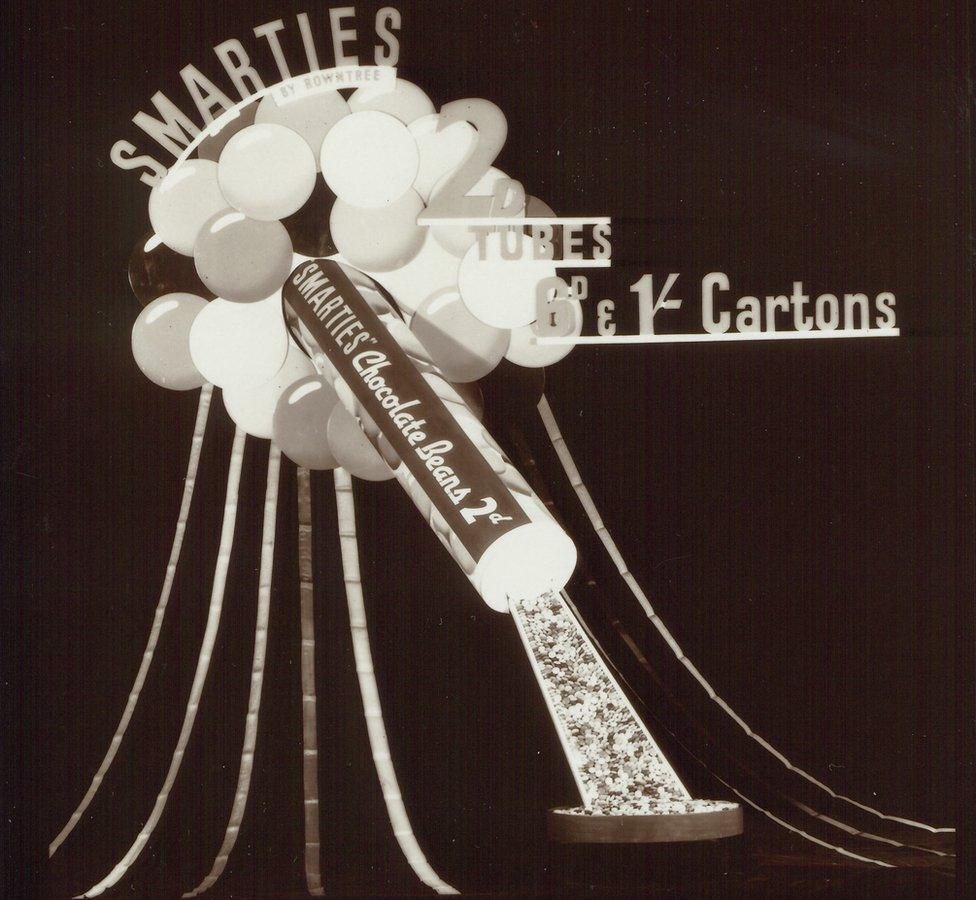

The brand proved a hit and by 1938, was so popular the firm had to build a new factory block solely for production of the sweet, which had to be expanded again just a few months later.

"Confectionery had been something to be had once a year, but in the 1930s it became affordable," said Miss Hutchinson.

"We know from board meeting minutes that we didn't predict they'd be that successful because the factory was only supposed to be one storey and we had to add four more.

"But Smarties had a certain magic. They were phenomenally successful."

You may also be interested in:

By 1939, the sweet came in four flavours - milk, plain, coffee and orange - and were sold in their now iconic cardboard tubes - a "fashionable" form of packaging that did away with the costly and clunky tins, said Miss Hutchinson.

This boom, however, was short-lived. Shortly after the outbreak of World War Two, production was stopped.

"We were instructed we couldn't use milk in confectionery, but we were able to make some plain chocolate, like KitKats, which came in a blue packet," said Miss Hutchinson.

"But then a year later, we had to stop making confectionery full stop, except for ration chocolate.

"And Smarties were gone."

For years Chocolate Beans were sold loose from the jar

Although the war ended in 1945, shortages continued and sugar rationing lasted until 1953., external

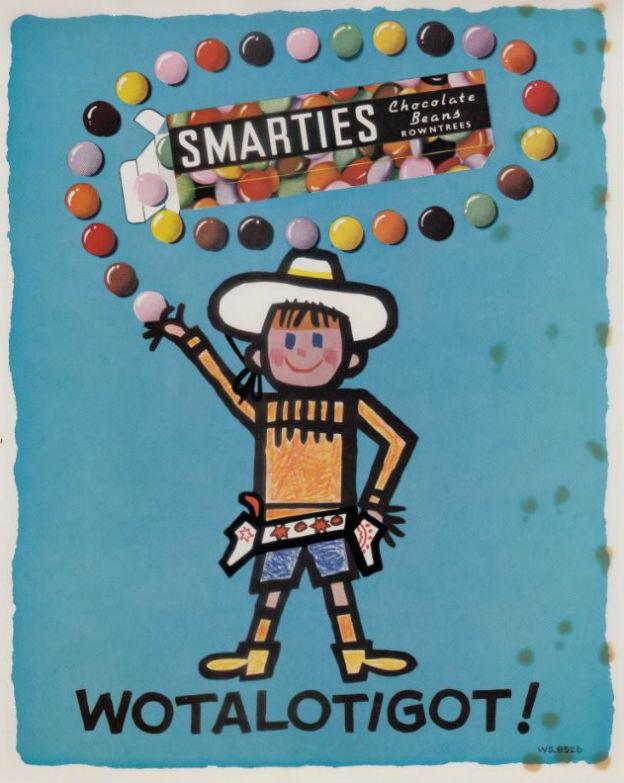

When production restarted in the 1960s, the Smarties campaigns were "huge", said Miss Hutchinson, and their multi-coloured cheer made them one of Nestlé's most popular post-war products.

But the brand, which Nestlé claims a third of UK households buy on a regular basis, would not be without its controversial moments.

Claude Gaget introduced Joseph Rowntree to pastilles and fruit gums

The sweet was so popular the confectioner had to build a special factory block for production

In 2005, Nestlé axed its cylindrical tube, external, much beloved by collectors hoarding the lids imprinted with letters, aliens and football phrases, external, in favour of a hexagonal shape.

The following year, it phased out its blue Smartie amid concerns over artificial additives and replaced it with a neutral-coloured white Smartie.

And although it seems the firm has no plans to reinstate the old tube for nostalgia's sake, the fuss kicked up by blue sweet fans had an impact.

In 2008, the firm started using spirulina - a form of sea algae - to dye the shell and the blue Smartie was reborn.

The orange-only tube of Smarties was created after countless requests from customers

And this year, after much lobbying from citrus addicts, the confectioner has released an orange-only tube of Smarties, external.

"It's been incredibly popular. We knew they were our most requested product and we knew people loved them, but we've been overwhelmed by how much," said Miss Hutchinson.

"I can't make windows into other people's souls and answer why people love the orange ones so much, but it's been surprising and wonderful.

"They've been more successful than we could have imagined."

- Published24 January 2016

- Published28 December 2015