The youngsters keeping traditional trades alive

- Published

Leighann Perry decided higher education wasn't for her and became a leatherworker

In 1999, the Labour government set out a pledge that half of all young people should go on to higher education - an aim that has almost been achieved. But what about those youngsters who do not want to go down the academic route? The BBC has met five who have become apprentices in some of Britain's oldest trades.

Leighann Perry, leatherworker

Leighann Perry developed an interest in the trade after working at Walsall's leather museum

"There are still companies making leather products?"

This is the response 22-year-old Leighann Perry encounters almost every time she says she works in the leather industry.

She developed an interest in the trade after working at Walsall's leather museum.

"People are always shocked to see me being so young working here in this industry. Everyone expects me to have an office job or something."

Walsall is a town built on leather and its mark runs through it: Saddlers is the nickname for both the football team and the shopping centre.

Whitehouse Cox has been making leather goods, from wallets to luggage, in the town since 1875.

It offered Leighann a three-year apprenticeship in leatherwork when she was 18.

Whitehouse Cox has been making leather goods in Walsall since 1875

Production manager Adrian Harris said the company was "not bothered about A-levels and A grades".

"People need three things [to work here]," he said. "Common sense, good eyesight, and to be good with their hands."

Leighann, who struggles with her mental health, said her schoolteachers "thought apprenticeships were a waste of time".

"I was pushed to do college because I couldn't get my English grades. I wanted to go to university, but at the time it wasn't right," she said.

"I'm happy doing what I'm doing though. College, sixth form and universities - they're not the only way."

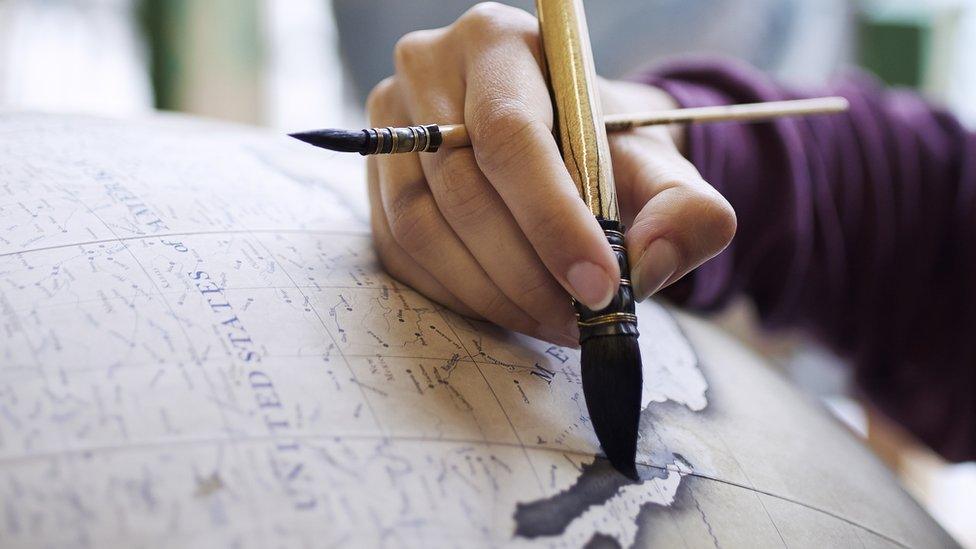

Eddy da Silva, globe-maker

Eddy Da Silva said Cristiano Ronaldo's success gave him the confidence to aim high

"There's nothing quite like holding the world in your hands," says Eddy da Silva, an apprentice globe-maker at Bellerby and Co. in London.

The 24-year-old, who was born in Venezuela but now lives in England's capital, left a corporate environment to pursue the craft but said "only a handful of people supported my decision".

"Having been in an office for two years, making globes is incomparable."

Eddy went to school in the Portuguese island of Madeira, where the success of a certain local footballer was as inspiring as the encouragement he got from his teachers.

"During this time Cristiano Ronaldo became a superstar, and having a fellow islander make it to that sort of height gave everyone a confidence boost, [that] 'impossible' was truly two letters too long," he said.

It takes at least six months to train as a globe maker at Bellerby's

Eddy said he had always been fascinated by globes but it was only after he followed Bellerby's on Instagram, where an apprenticeship in map-making had been advertised, that he turned his interest into a job.

"It has been quite surreal," he said. "I feel incredibly privileged to be doing something like this."

"You just have to have the ambition to seek out unique roles like this and be a bit of a risk-taker."

You might also be interested in:

JoJo Wood, clog-maker

"People think of craft as something you do as a hobby, cutting and sticking type stuff"

"Craft is seen as the stupid option. It's what you do if you can't do maths."

JoJo Wood has been making wooden spoons and clogs since childhood, following in the footsteps of her parents in a trade as old as time.

"As a kid, whittling sticks, playing with knives and making things is something I always did," said the 23-year-old, who grew up in Edale in Derbyshire.

"At 18, when I started getting into [woodwork], people thought I was mad. But as they've got to university and their hope for the future has gradually dropped off, suddenly it doesn't seem so bad."

Could you turn a log into a wooden spoon?

Now based in Birmingham, JoJo is halfway through a woodworking apprenticeship with master clog-maker Jeremy Atkinson and also runs her own spoon-making business.

"Jeremy is still working but he's very aware of the fact that he's got a very arthritic wrist, he's got a bad back, and at some point it's going to get to the stage where he can't work any more," she said.

The crafter believes ancient skills have a place in the modern world and thinks it is important young people are better connected to these industries.

"There's a backlash against throwaway culture," she said.

"People want to buy something that's made well and going to last, not just a bit of plastic ordered off the internet from China that's going to end up in landfill in a year's time."

George Richards, wheelwright

"None of my friends or apprentices I know are doing anything as unique as wheelwrighting"

"I'd like to think I'll be a wheelwright for the rest of my life," says 20-year-old George Richards.

Five years ago, he asked for work experience with Mike Rowland & Son Wheelwrights and Coachbuilders in Colyton, Devon.

He was not very academic at school but didn't have much help to consider options other than college.

"They weren't really interested if you weren't going on to do that," he said. "But for some people, [apprenticeships are] the only thing that suits them."

Mike Rowland and his son Greg are two of about 20 master wheelwrights in the country.

George believes there will always be lots of work for wheelwrights

Their company has a history of making wooden wheels for carriages and cannon dating back to 1331, and counts the Queen as one of its customers.

Greg thinks George is probably the youngest qualified wheelwright in the world.

When asked what inspired him to choose such a niche trade, the apprentice is frank.

"It was nothing to do with wheelwrighting [as such]," he says. "It wasn't something I'd thought I really wanted to do.

"It was just working with my hands, working with wood - I knew I loved that."

Zoe Collis, paper maker

"In a way, this is blissful. I'm allowed to take my time here, and it's so peaceful"

Zoe Collis describes working at Two Rivers Paper Company as "the best thing that's ever happened to me".

The 19-year-old said college was "a lot of pressure" that caused "anxiety and stopped me excelling".

"My parents were adamant I went to college, but I never thought it was something I wanted to do. I was more interested in hands-on stuff."

Zoe joined the firm in Watchet, Somerset, which specialises in making watercolour paper for artists. It claims to be the only place in the UK where paper is made from old rags using water power.

Fourth-generation paper maker Jim Patterson mentors the teenager in his trade.

"I'm getting on, I'm an old man now and I'd like the business to carry on the craft," he said. "Having someone younger encourages us to be thoughtful; it helps us question things."

Zoe feels it was the right move to spurn the more mainstream routes into employment.

"A lot of my friends are miserable because they can't get a job or they're doing something they don't want to do. I definitely feel better off than that."

The apprentice expects to be making paper "probably until I'm pushing up daisies".

"My future is brighter now I have this apprenticeship. Before, I was just seeing dead ends."

Training an apprentice for just one day can reduce a craftsperson's income by 20%, according to the Heritage Crafts Association (HCA).

Money for training is scarce, says its trustee Greta Bertram, because "funding follows qualifications", and not enough is done to encourage students who could thrive in traditional industries.

"There's virtually no craft career education in schools," she said. "And if people aren't exposed to making, they don't develop a taste for it."

A Department for Education spokesperson said: "We have 43 apprenticeships in the creative and design category, which includes traditional craft apprenticeships.

"Schools must allow providers of technical education and apprenticeships access to talk to pupils about their offer. This will help young people to hear about the full range of options available to them and make an informed choice about their future."

- Published19 July 2014

.jpg)