Actresses and arsonists: Women who won the vote

- Published

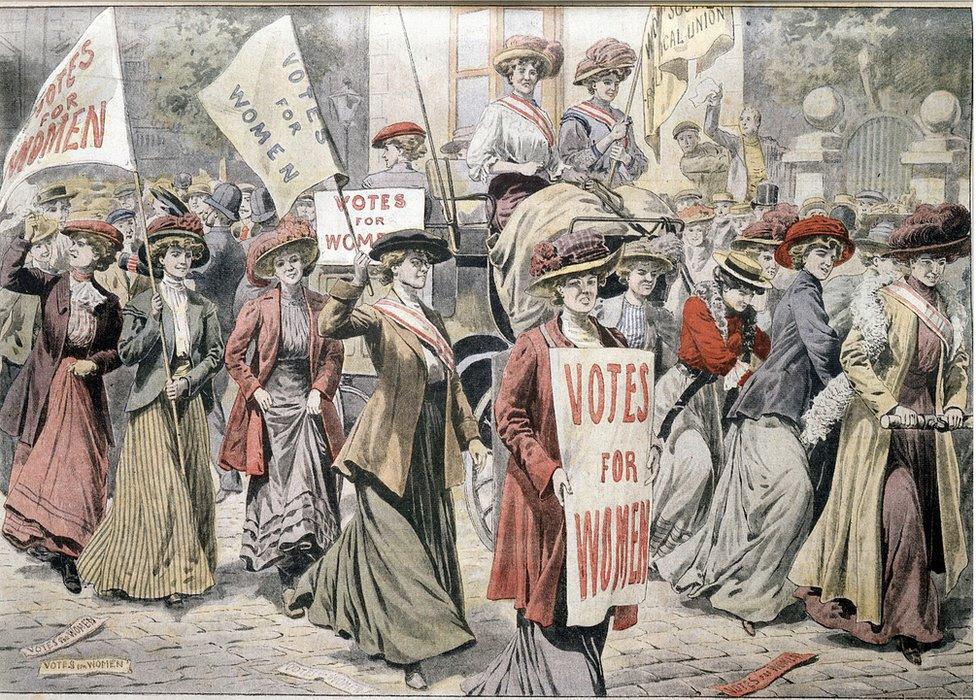

Before 1918 no women were allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. It took the extraordinary actions of ordinary women to bring the issue to the forefront of politics; women who were prepared to go to prison, to go on hunger strike, to be force fed - just to achieve parity with men.

Two branches emerged - the suffragists used peaceful tactics such as non-violent demonstrations, petitions and the lobbying of MPs; while the suffragettes' methods were more militant, smashing windows and setting fire to buildings.

Most people have heard of the poster girls of women's suffrage, such as Emily Wilding Davison and the Pankhursts, but here are some of the lesser-known women - and men - who dedicated themselves to the cause.

The dancer-turned-arsonist

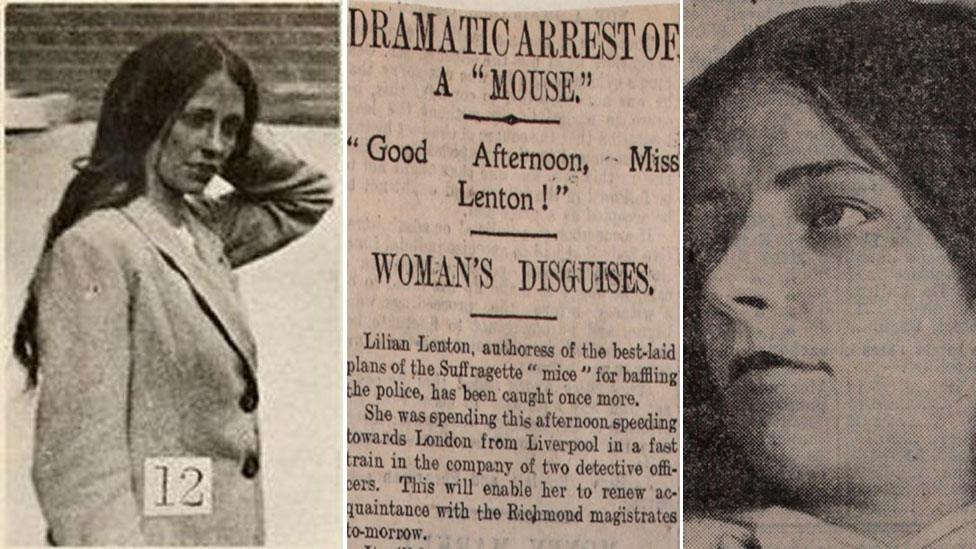

Lilian Lenton photographed in a prison exercise yard, and newspaper coverage of her escape and arrest

Lilian Lenton, a firm believer in the suffragettes' motto "deeds not words", had an ambition of burning down at least two buildings a week. She trained as a dancer when she left school but became a suffragette as soon as she turned 21. She quickly became famous for her ability to escape from the authorities.

Moving from her hometown of Leicester to London, early in 1913 she began a series of arson attacks in the capital. Her object was to bring the country into crisis, showing that it was impossible to govern those who did not want to be governed.

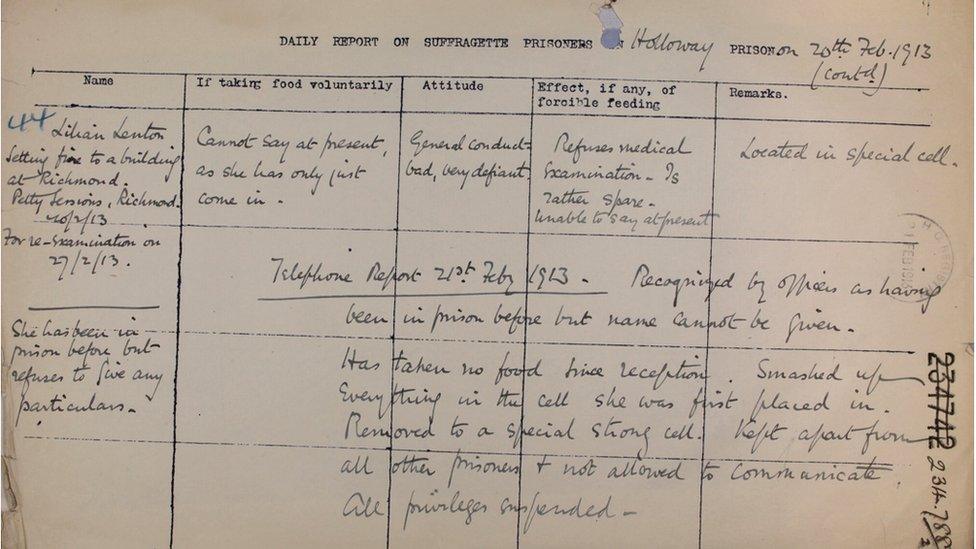

She was arrested in February 1913 for setting fire to the Tea House at Kew Gardens and in Holloway prison went on hunger strike before being forcibly fed. The process, which involved stuffing a tube through her nose and down her throat, caused her to become seriously ill as she breathed food into her lungs.

She was quickly released. The authorities did not want a martyr.

You can hear Lilian Lenton speaking here

However, her time in jail only made her more determined. She continued her campaign of arson and was soon jailed again in Leeds before being released under the "Cat and Mouse Act", external when she went on hunger strike.

A prison report from 1913, which describes Lenton's general conduct as 'bad, very defiant' and details how she was put in a special cell after smashing the first one up

Fearing she would be rearrested once recovered, she fled the city in a delivery van, dressed as an errand boy. Taxis took her to Harrogate and then Scarborough from where she escaped to France in a private yacht, although she soon returned to Britain, setting fire to things again.

This act of evasion earned her the nickname of "the Leicester Pimpernel".

A newspaper cutting from May 1914 describes how she evaded capture.

"She led the police a merry dance up and down the country for several weeks while she changed her disguises. Harrogate, Scarborough and Dundee were a few of the towns she visited. She also stayed at Cardiff. There she was nearly caught, but by disguising herself as an infirm old lady, with a black shawl over her head, she hobbled into the station and travelled to London".

During World War One, she served in Serbia with a hospital unit and was awarded a French Red Cross medal.

After the war the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed, awarding the vote to women householders or the wives of householders, aged 30 and over.

Lenton, who was unmarried and did not own a home, was unimpressed by this concession. "I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30," she said.

She died aged 81, in 1972.

The actress-turned-activist

Elizabeth Robins was a successful actor

Elizabeth Robins was an American actor and playwright brought up by her grandmother after her mother was committed to an insane asylum. She married an actor and was far more successful than him - he eventually killed himself by jumping into a river, leaving a note to her saying: "I will not stand in your light any longer."

Robins came to London in 1891 to play the lead in Ibsen's, external Hedda Gabler, becoming the pre-eminent Ibsen actress of her day. By 1906 she had begun to focus on women's suffrage as a subject for drama.

In the autumn she wrote Votes for Women!, external in which one of the main characters is based on suffragette leader Christabel Pankhurst. The play was a success and performed all over the country. She later adapted it into a book - The Convert - which is still in print.

Robins took the production to New York and Rome, helping to spread the message. She gave some of the proceeds to the suffragette movement.

As suffragette militancy increased, she wrote articles and letters in support.

Other than her brief marriage, she remained single. Highly intelligent, she was welcomed into London's literary and artistic circles, enjoying friendships with George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, and Henry James.

She continued to campaign on feminist issues for the rest of her life, even turning her house into a convalescent home for overworked professional women. She was also a driving force behind the founding of the New Sussex Hospital for Women and Children.

The shopgirl who became a cabinet minister

Margaret Bondfield was one of very few working class women who rose to the top of the suffrage movement.

Born in Chard, Somerset, in 1873, the second youngest of eleven children, she became an apprentice at a drapers in Brighton aged 14.

There she saw how the daily grind wore down the women workers and affected their self-respect. She observed they were left with little time or energy to pursue interests away from work, with many girls seeming intent on getting married as early as possible in order to escape the drudgery.

Ms Bondfield left Brighton and went to live with her brother in London - working, again, in a shop. She became an active trade unionist and was shocked by the working culture of long hours, low wages, poor diet and requirement to "live in" in often dismal dormitories.

She co-founded the first trade union for women, the National federation of Women Workers, and later recalled how one irate grocer "read a recruitment leaflet, tore it up and stamped on the bits", shouting: "Union indeed! Go home and mend your stockings!"

By 1910, she was working as an advisor to the Liberal government - helping to influence the Health Insurance Bill, giving improved maternity benefits to mothers, and working to further gender equality.

In 1923 she became one of the first female MPs, winning Northampton for Labour, and in early 1924, she made history when she was appointed as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Labour - the first woman ever to become a government minister. In 1929 she was made Minister of Labour herself - the first time that a woman had been made a British cabinet minister.

She remained a staunch Labour supporter until her death at the age of 80.

Clement Attlee, the leader of the party and former prime minister, gave the address at her funeral.

The power couple ousted by the Pankhursts

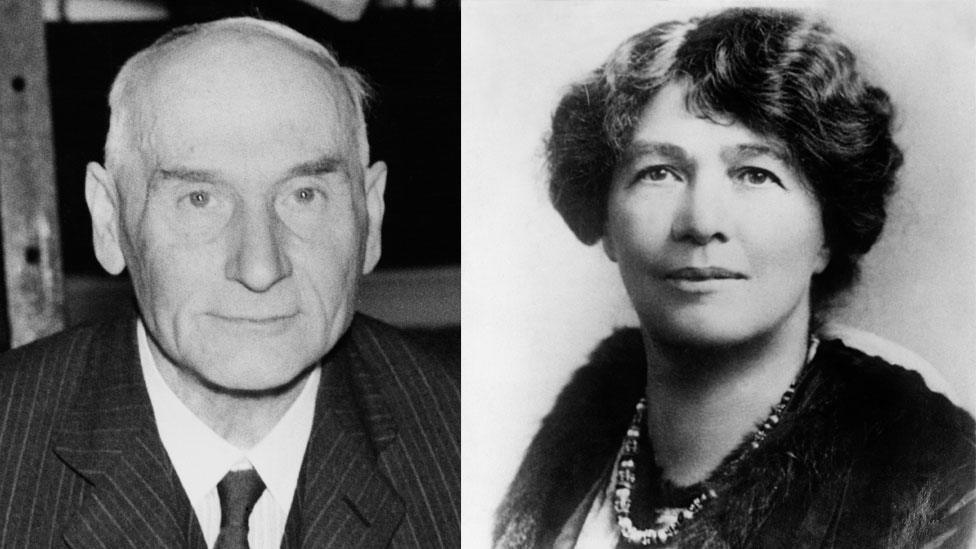

Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were both prominent suffragettes

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and her husband Fred were a suffragette power couple.

Emmeline Pethick had a strong social conscience and worked with working class girls in London to improve their living standards and employment prospects. Frederick Lawrence was a barrister from a wealthy family, who had aspirations to become a Liberal MP. When the pair fell in love, Miss Pethick refused to marry him until he became a socialist.

The couple agreed to combine their names, but continue to hold separate bank accounts. His money and her organisational skills helped the Women's Social and Political Union, the radical organisation led by Mrs Pankhurst, rise to prominence.

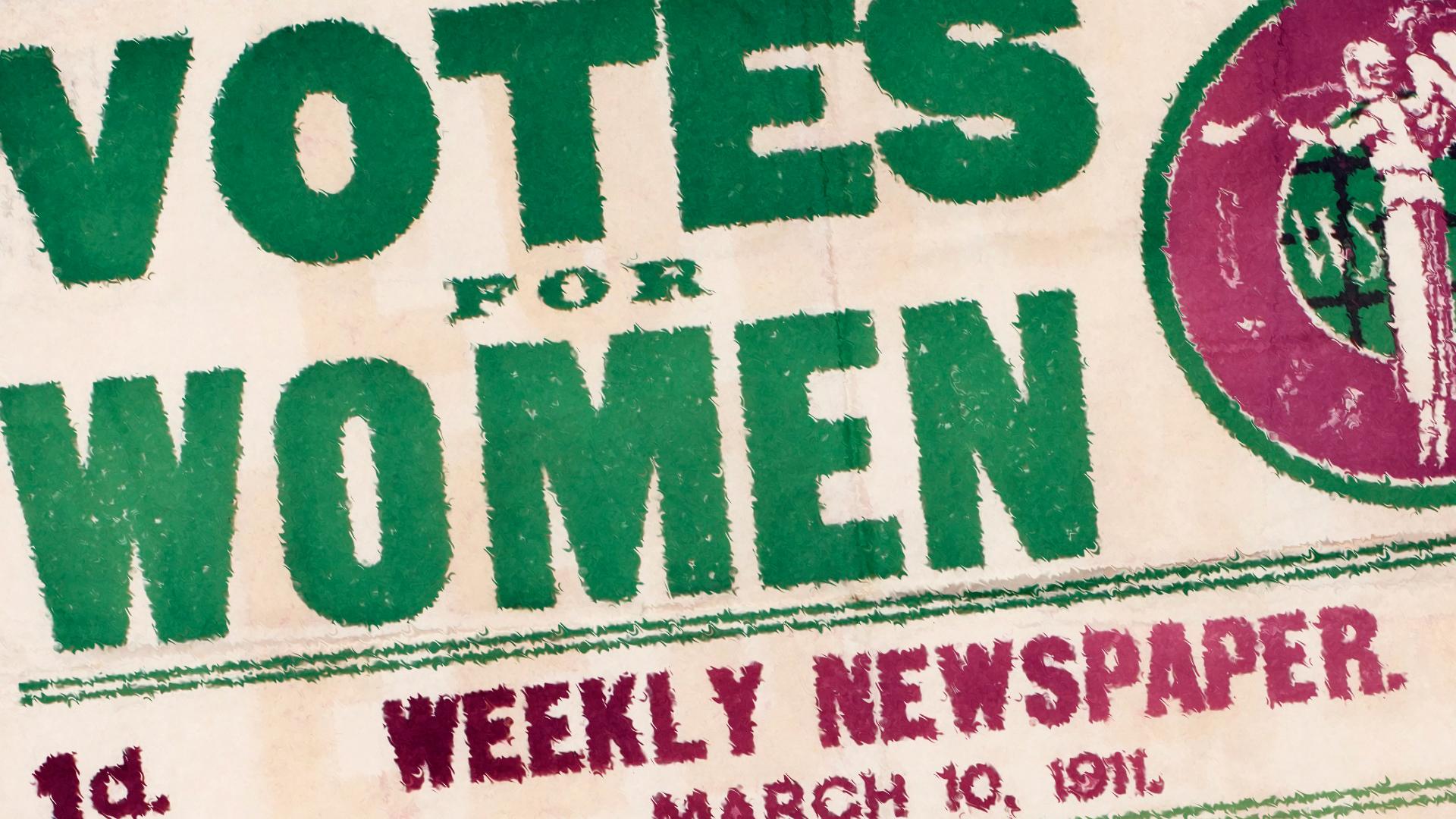

Campaigns were planned at their country home, which was also used as a place where women released from prison could recuperate, and together they ran the publication Votes for Women.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence came up with the colours of purple, white and green to represent the suffragettes: "Purple as everyone knows is the royal colour, it stands for the royal blood that flows in the veins of every suffragette, the instinct of freedom and dignity… white stands for purity in private and public life… green is the colour of hope and the emblem of spring."

After World War One, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence became an international campaigner for women's rights and peace. Her husband became a Labour MP, and in 1945, a peer.

But, as influential and helpful as they were, the Pethick-Lawrences fell out with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, who preferred militant action.

The couple disapproved of the campaign to smash windows, but because of their involvement with the group, they were arrested, charged with conspiracy and jailed for nine months.

Both went on hunger strike, both were force-fed.

Mrs Pethick-Lawrence said: "If the government was naive enough to believe the nasal tube or the stomach pump, the steel gag, the punishment cell, handcuffs and the straight jacket would break the spirit of women who were determined to win the enfranchisement of their sex, they were again woefully misled".

The courts also took the contents of their home to pay for the cost of the windows. Just as damaging were the prosecution costs. Bailiffs were called in and the couple only narrowly avoided bankruptcy.

When the WSPU planned to move on to campaigns of arson, the Pethick-Lawrences objected. Christabel Pankhurst then arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation.

"Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us," Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence later recalled.

Despite being pushed to one side, the Pethick-Lawrences continued to campaign for equality.

In 1928, the Equal Franchise Act, external granted equal voting rights to all women and men aged 21 or over.

At a celebratory gathering, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence thanked the government for the new law, saying: "We have fought a good fight."

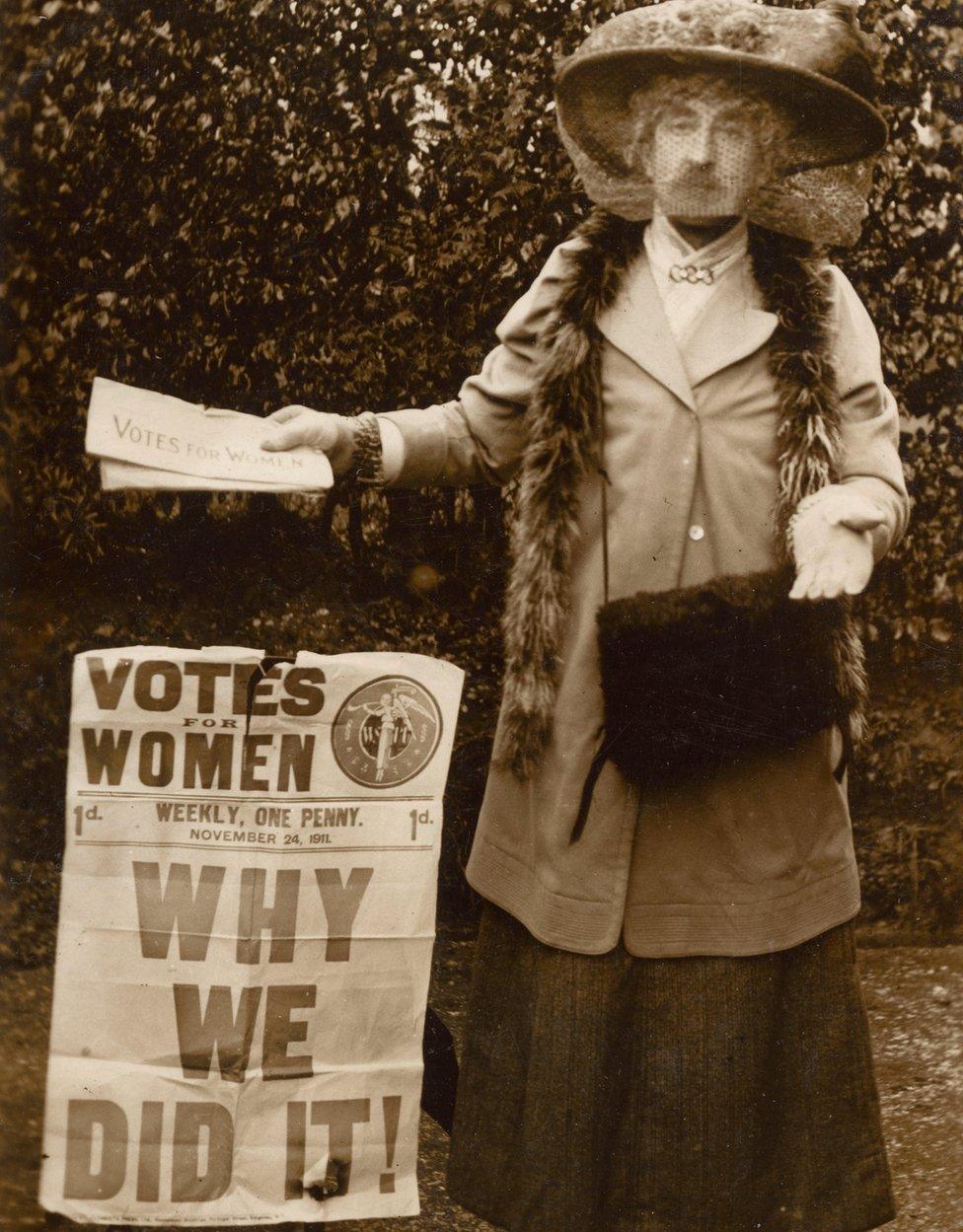

Frederick Lawrence dressed as a female suffragist, brandishing a copy of Votes for Women

BBC Local Radio will sharing stories of these and other women from 6 February using the hashtag #1918women.

- Published6 February 2018

- Published2 February 2018

- Published22 January 2018