How UK women get the vote: Suffragettes, suffragists and the Representation of the People Act 1918

- Published

100 years ago, the law changed to give women the right to vote for who represented them in Parliament. Find out more about two women in particular who fought to make this happen

100 years ago - on 6 February 1918 - an important law was passed which changed the UK forever.

It was called the Representation of the People Act 1918.

What was this law?

The Representation of the People Act 1918 was an important law because it allowed women to vote for the very first time. It also allowed all men over the age of 21 to vote too.

Before this law, women weren't allowed to vote in general elections at all. Some men could vote, but not all of them - for example, a man had to have property in order to be able to vote, so it excluded people who weren't as wealthy.

The contribution made during World War One by men and women who didn't have the right to even vote was an important reason for the law changing (find out more about this below).

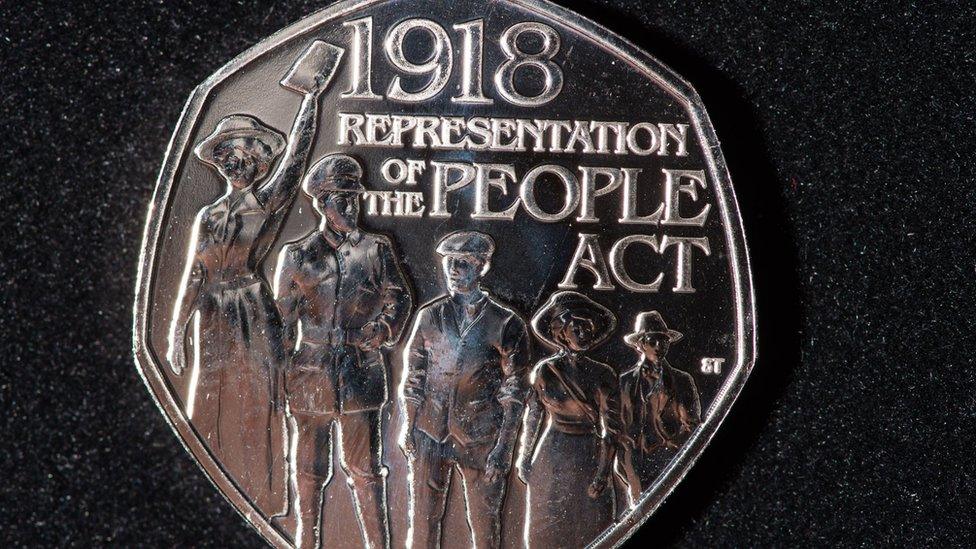

The Royal Mint, which makes the UK's money, released a special 50p coin to mark 100 years since the Representation of the People Act 1918

But even after the Representation of the People Act 1918, men and women still didn't have the same rights when it came to politics.

The law said that women over the age of 30 who occupied a house (or were married to someone who did) could now vote. This meant 8.5 million women now had their say over who was in Parliament - about 2 in every 5 women in the UK.

It also said that all men over the age of 21 could vote - regardless of whether or not they owned property - and men in the armed forces could vote from the age of 19. The number of men who could now vote went from 8 million to 21 million.

So the situation was still very unequal between men and women.

What happens when you're not allowed to have your say?

It was another 10 years before women were allowed to vote in the same way that men could.

What is equality?

However, the Representation of the People Act 1918 was an important step in the fight for getting equality for women in society.

So what's the story behind it?

Voting in the past

In a democracy, like the UK today, members of the public get to vote for who they want to lead them and have more say in how the country is run.

But this has not always been the case. In the past, the King or Queen had huge powers and there was very little that ordinary people could do to have a say in how they were governed.

In the early 1800s, there were still very few people who could vote - and the ones that could were all men. Women didn't have a say at all.

The UK is a democracy, which means that members of the public get to have their say over who represents them in Parliament

But around this time, things started to changed. Throughout the 19th Century, groups like the Chartists campaigned to allow all men to be able to vote.

In 1832 and 1867, laws were passed which did allow more men to vote than could before, but they still didn't apply to all men. For example, men still had to be quite rich to have their say.

Meanwhile, women were still not allowed to have a say at all in who was in Parliament.

The role of women

Up until Victorian times (1837-1901), women had very few rights at all, especially once they were married. For example, anything they owned became their husband's property.

It was also traditionally thought that women shouldn't be part of politics. Even Queen Victoria agreed!

Even Queen Victoria didn't think that women should have anything to do with politics

It was felt a woman's place was at home, raising children and running the household.

More and more women were working in full-time jobs though. This made it easier for them to get together to discuss politics and issues which affected their lives - and many of them weren't happy about how society treated them so differently to men.

Time for change

When the laws were passed in the 19th century that gave men more voting rights, and women were still left out, they began to campaign for their right to be able to vote too.

Women wanted more equality in society in general, but their right to vote became the focus of their fight. There were men who campaigned for their right to vote too, but it was not a popular opinion.

'Equality is all about having a fair chance'

The first petition to Parliament asking for women to get the vote was presented by a man called Henry Hunt on 3 August 1832, but it was not successful.

Then, in 1867, a man called John Stuart Mill suggested to Parliament that the law should be changed to give women the same voting rights as men. His proposal was also rejected by 194 votes to 73 - but it got the campaign going. (It's worth mentioning that there weren't any women in Parliament at this point!)

John Stuart Mill, pictured here, thought that women deserved the right to vote too

Changes to the law in favour of women getting the vote were presented in Parliament almost every year from 1870 onwards. But they weren't successful, so some women felt the campaign needed to be turned up a notch!

One woman in particular who was very important in the fight for women's right to vote was Emmeline Pankhurst.

Who was Emmeline Pankhurst?

In 1903, she helped to start a group called the Women's Social and Political Union. Members of this group became the first suffragettes - a group of women who fought hard for women's votes.

They got their name from the word suffrage, which means right to vote.

As part of their campaigning, suffragettes used to carry out demonstrations, which were sometimes violent. In order to get their message heard, they would smash windows, set fire to politicians' postboxes, refuse to eat and chain themselves to railings.

The suffragettes used to get in trouble with the police. In this photo, a member of the group is being arrested by police officers during a protest outside Buckingham Palace in 1914

One suffragette called Emily Davison even gave her life for the cause, when she was killed after running out in front of the King's horse.

Many people supported women's right to be able to vote, but did not agree with the violent action of the suffragettes. They preferred to hold meetings, parade with banners, write letters or sign petitions.

Suffragettes: Who was Emily Davison?

A group called the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which was formed in 1897, believed in using non-violent tactics to persuade the country that women deserved the vote.

They were called the suffragists and were led by another important figure in the fight for women's right to vote - a woman called Millicent Fawcett. Emmeline Pankhurst had been a member of this group originally.

Although the suffragists and the suffragettes used different methods, they both had one goal in mind - get women the vote.

World War One breaks out

In 1914, World War I broke out.

Many women took on jobs that men traditionally did, while they were away fighting.

Emmeline Pankhurst focused her efforts on helping the war effort and encouraged other suffragettes to do the same. She pointed out that there was no point in continuing to fight for the vote when there might be no country in which they could vote!

During the war, many women took on jobs that men would traditionally do - for example, working in factories

Doing this gained for the women fighting for suffrage a lot of respect.

During this time, there were no elections to choose a new government - and attitudes to women in society really started to change.

A big reason for this was because of the contributions that women had made to society throughout the war.

Women proved themselves to be every bit as equal as men and the government promised to give women the vote when the war was finished.

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act was passed in February and women voted in the general election for the very first time in December that year.

What has happened since?

The work done by the suffragettes and suffragists in the years leading up to World War I was extremely important for women getting the right to vote.

But it wasn't until a law called the Equal Franchise Act in 1928 that suffrage was extended to all women over the age 21, meaning that women finally had the same voting rights as men.

Up until 1918, women hadn't been allowed to be MPs in Parliament either. But a different law was passed in the same year as the Representation of People Act which changed this too. In December 1918, the first woman was elected to the House of Commons.

The woman on the right in this photograph is Constance Markievicz, the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons, in the general election of 1918

The UK has come a long way since then in treating women the same way as men.

Before the 20th Century, there had certainly been no female prime ministers. Now, there have been two - including recent Prime Minister Theresa May - and there are many female MPs.

But there are still more male MPs in Parliament that there are women and there is still inequality in the UK between men and women in other areas of life.

What's it like to be a girl in 2018?

People are also treated differently because of their gender in other countries around the world, so there is more work to be done - both in the UK and in other countries.

Many people continue to fight for equality with the hope is that one day everybody will be treated the same all over the world, regardless of their gender.

- Published30 January 2018

- Published3 December 2019

- Published5 May 2016

- Published7 March 2023