England's pioneering black head teachers

- Published

Yvonne Conolly became a London head teacher after travelling in a "posh banana boat" from Jamaica

It is 50 years since the first wave of black head teachers took up their roles in English schools, yet ethnic minorities remain under-represented in senior roles.

BBC News Online examines the impact of these pioneers of the profession as they overcame prejudice and multiple rejections on their rise to the top of their field.

'I remember sitting at a bus stop with tears rolling down my face'

Yvonne Conolly, who was head teacher at Ringcross Infant School, in Highbury, London from 1969 to 1976, arrived in England in 1963 in what she describes as a "posh banana boat" from Jamaica.

"The boat carried bananas in the hold but it was a nice ship upstairs and the food was superb," she said.

"I was 23 and had taught at a boarding school in Jamaica. I planned to study for a degree in education in Britain and return home. Of course, I ended up staying."

But life in London, where Mrs Conolly settled, was far from easy.

Yvonne Conolly at work in the classroom

"I was a supply teacher, living in Camden, but I was assigned to teach in Greenwich," she said.

"I had to get up at 5am. I remember sitting at a bus stop with tears rolling down my face, trying to work out which buses I needed to catch.

"You had to go to the education office to find out if they had any work and you might get all the way there, only to discover no school needed a supply teacher that day."

Mrs Conolly said she encountered some racism in those early days.

"I remember somebody at the office asking: 'Who are you?'," she said. "I replied, 'I am a supply teacher, allocated to this division'. They said, 'Oh, but you are black'. I said, 'Well, obviously, yes'."

Later, at a school she worked in, a white South African father told the head teacher he didn't want his son to be taught by a black teacher.

"The head told him, 'Tough - find another school'," Mrs Conolly said. "And the boy stayed in my class and blossomed."

Mrs Conolly says she was "flabbergasted" when she got the second headship role she applied for

Slowly but surely, she blossomed too. In the space of a few years, she moved from being a supply teacher to a temporary teacher to permanent staff to deputy head.

At the age of 29, her "wonderful" head teacher was encouraging her to apply for headship roles.

"I got the second job I applied for, at Ringcross," she said. "I was flabbergasted."

Again, there was some racist aggression.

"People cut out photos of me from the newspapers and wrote to the school, telling me to go back to where I came from and that I looked like a monkey," she said. "Somebody even threatened to burn the school down.

"On my first day, I was escorted into the school by one of the senior inspectors from Inner London's education authority because they took some of the threats seriously.

"But it was a happy school and the staff were excellent. It was in quite a poor area of London, but had a mix of children - some West Indian, some African, some European and some white middle class."

Mrs Conolly stayed at Ringcross for seven years. Later in her career, she helped set up a Caribbean Teaching Association and worked as an inspector for Ofsted.

"I never felt like a pioneer," she said. "Last year I was in Waitrose in Holloway and I noticed a young black woman was looking at me.

"She came over and said, 'Do you remember me?' She said it was because of me that she had gone into teaching and she was head of the business department in a secondary school. That was a wonderful thing to find out."

'She taught me to love literature'

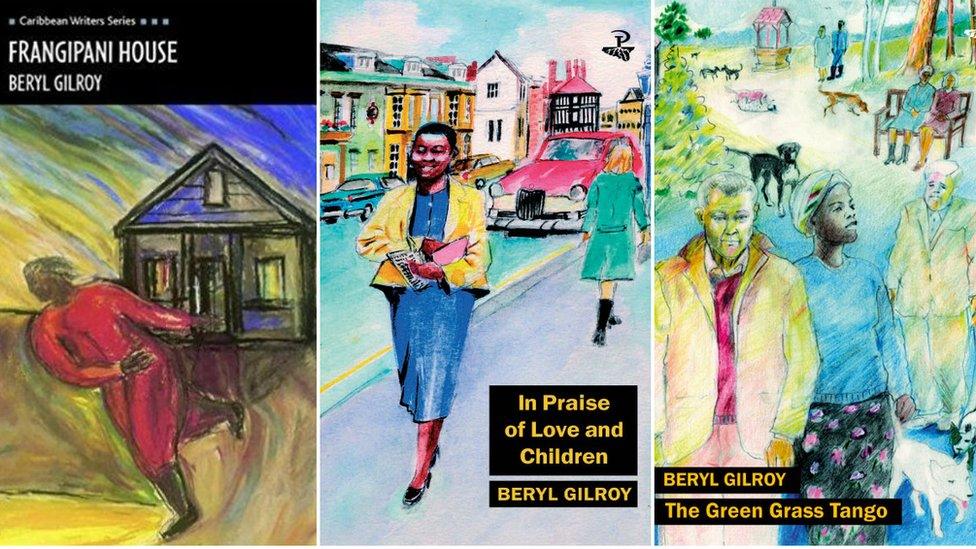

Beryl Gilroy was a successful author, as well as a popular head teacher

When Beryl Gilroy, who was head teacher at Beckford Primary in Camden, London from 1969 to 1982, arrived in the city in 1951 from her birthplace in Guyana, she stepped into a world that was both familiar and forbidding.

Her son Paul, a professor of literature at King's College London, said: "She had a British passport and as a colonial subject, she was already familiar with British culture and life. She knew more about the flora and fauna of this country than her own."

However, this was also the time of the colour bar and, as Mrs Gilroy sought accommodation, she was confronted with signs saying: "No dogs, no blacks, no Irish".

Eventually, she found a home with a family of Jewish refugees.

Although Mrs Gilroy had taught in Guyana, her qualifications were disregarded by the education board and she had to study to resume her career.

"She worked as a maid, as a cook, while completing her second education," said Prof Gilroy. "She was a resilient character."

Eventually, Mrs Gilroy was able to begin her British teaching career and, after working in schools across London, found a niche teaching at primary level.

With support from a senior colleague, she became head at Beckford - although her ascent attracted some harassment.

Beryl Gilroy became a successful author alongside her teaching career

"Things would pop up in the mail - racist abuse, that kind of thing," recalled Prof Gilroy. "She definitely found these things stressful.

"But my mother became hardened in her opposition to these forms of idiocy and her commitment to making the country a better place."

Mrs Gilroy joined the Race Relations Board but also became a successful author alongside her teaching career, with Frangipani House being one of her best-known works.

"She wrote all the time - children's and adult books," said Prof Gilroy. "She taught me to love literature and the craft of writing and I will always be grateful to her for those gifts."

When Mrs Gilroy died at the age of 76 in 2001, she was described as, "one of Britain's most significant post-war Caribbean migrants, external".

Prof Gilroy sees her legacy as being instrumental, alongside her fellow ethnic minority head teachers, in shaping the country we know today.

"These teachers created something like a living cosmopolitan culture," he said. "It was constructed in the most difficult of circumstances and that probably makes us unique in Europe."

'An inspirational man'

Tony O'Connor (front, centre) did much to improve race relations at a difficult time in Smethwick's history

The man who was believed to have been Britain's first black head, Tony O'Connor, was appointed as head teacher at Bearwood Primary School in Smethwick, West Midlands, in September 1967. He would spend 16 years in the job.

In 1967, race relations in Smethwick were troubled. Peter Griffiths's election as Smethwick's MP in 1964 followed arguably the most racist electoral campaign in British history.

The local council kept news of Mr O'Connor's appointment secret for a few weeks as they feared a backlash.

Peter Griffiths's election campaign to become Smethwick's Conservative MP in 1964 was arguably the most racist in British history

Within days of the announcement, in December, the school walls were daubed with swastikas and racist slogans.

Yet Mr O'Connor, a former RAF sergeant who had served in World War Two, rose above the taunts and threats.

He was quoted in The Times as saying: "I don't care if I am the first, second, third or 250th West Indian headmaster.

"I am only interested in carrying out the instructions of the committee which appointed me - to take care of the school and the education of the children."

Mr O'Connor's son-in-law, Dr Victor Cross, describes him as an "inspirational man".

At one stage, the head teacher felt so threatened he moved his young family away from his home to stay with a relative but he refused to let the pressures affect his care for his pupils.

According to contemporary newspaper reports, parents appreciated his efforts.

Smethwick was infamous for its racial tensions in the 1960s

One, Kathleen Allmark, said: "Mr O'Connor is a very fair man. All the children seem to like him and we are very satisfied."

"Tony O'Connor proved to be a very popular head teacher," said David Hallam, former Smethwick councillor and local historian.

"Sadly, his name has almost been lost."

Mr Hallam is working with the school in a bid to have his headship better celebrated.

"His story should be told," he said. "He overcome bigotry and did much to improve race relations in the area."

'A system that still isn't colour-blind'

Despite the achievements of England's first black head teachers, the ethnic make-up of those in senior teaching roles remains broadly static with 93.5% of heads describing themselves as "white British", external.

Back in 1985, a government report by Lord Swann, external noted there were "disproportionately low numbers of teachers of ethnic-minority origin in our schools" and called for a response - but little has changed.

Gilroy Brown, whose family came from Jamaica to settle in Wolverhampton and who served as a head teacher at Foundry Primary in Birmingham for 10 years from 1989, said there were many reasons why ethnic minorities were still "sadly, significantly under-represented" at headship level.

"If young people don't have a positive experience at school, they won't aspire to become teachers or head teachers," he said.

Gilroy Brown was a head teacher for 10 years

According to research by Chris Vieler-Porter, who is studying for a doctorate at the University of Birmingham on the underrepresentation of black and ethnic minority people in educational leadership roles, just 37% of local authorities monitor the number of applications for such roles by gender, ethnicity and disability.

"The people who are making decisions are not looking at these issues," he said.

"We have a system that believes itself to be colour-blind and obviously isn't."

Mr Brown said he wanted to see a national campaign to recruit teachers from minority backgrounds.

"Had we done this in the 80s, when I became a head, we would have a much better representation now," he said.

"That said, I'm glad to have done my bit."

- Published1 June 2016