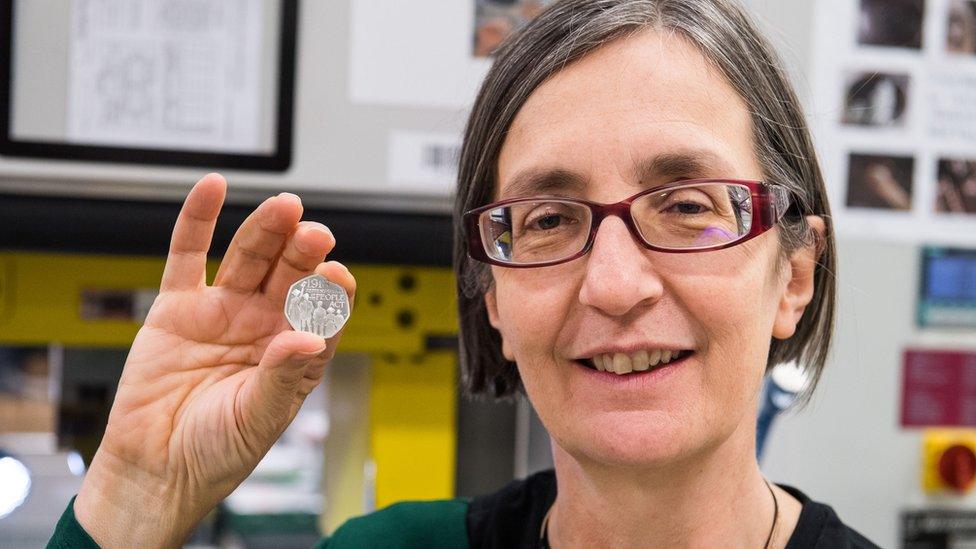

Unused ticket: The suffragette story in seven objects

- Published

Women have only been allowed to vote in national elections for the past 100 years. One group fighting for female suffrage - the Women's Social and Political Union - used violence, smashed windows and set fire to buildings.

The Daily Mail newspaper gave them the nickname "the suffragettes". The term was meant to be derisory - it turned out to be defining.

Here are some of the artefacts that illustrate their story.

Hunger strike medal

The silver bar is inscribed "For Valour". The ribbons are in the WSPU colours of purple, representing dignity, white for purity and green for hope

These medals were first presented by the Women's Social and Political Union in August 1909. Many campaigners, both men and women, were jailed for their involvement in the suffrage movement.

Under the slogan "deeds not words", some activists smashed windows, threw stones and burned buildings. Once imprisoned, they would go on hunger strike.

Their refusal to eat led to force-feeding - where a tube was forced up a striker's nose and down the throat before food was poured in. Sometimes the feeding pipe was put in incorrectly and food would be forced into the lungs, which can be fatal.

Force feeding attracted public disapproval - and eventually the government brought in a bill known as the Cat and Mouse Act, which allowed seriously ill hunger strikers to be released until they regained their strength, when they would be re-arrested and jailed again.

This particular medal belonged to a Genie Sheppard.

She was arrested at a demonstration in the West End of London where she and other women smashed windows with stones and hammers.

In Holloway Prison she went on hunger strike, and the medal is engraved with the words: "Fed by Force 1/3/12".

Bolt cutters

In 1908 a Porter's Easy Bolt Clipper (large shears about 2ft 6ins (76cm) long) was obtained through HM Office of Works to cut the chains with which suffragettes might secure themselves to portions of the building

Women wanting to know what was going on in the House of Commons had to watch from a special gallery, which had windows covered with metal grilles. The grilles were difficult to see and hear through and became both a physical and symbolic representation of how women were excluded from the heart of decision-making in the country.

In 1908, Helen Fox and Muriel Matters attached themselves to the grille with padlocks and refused to give up the keys. Eventually the grilles had to be removed in order to eject the women.

The authorities learned from this and invested in a set of bolt cutters, which were considered a sound investment the following year when three women chained themselves to statues in the Central Lobby.

The women were quickly snipped free and expelled.

The police report to the Serjeant at Arms concludes: "I beg to add that the clippers turned out most valuable in this case as it was only the work of about 7 or 8 minutes from the commencement to the end of the whole proceedings."

An image in the Illustrated London News shows policemen cutting the chains of suffragettes who attached themselves to the railings at Downing Street

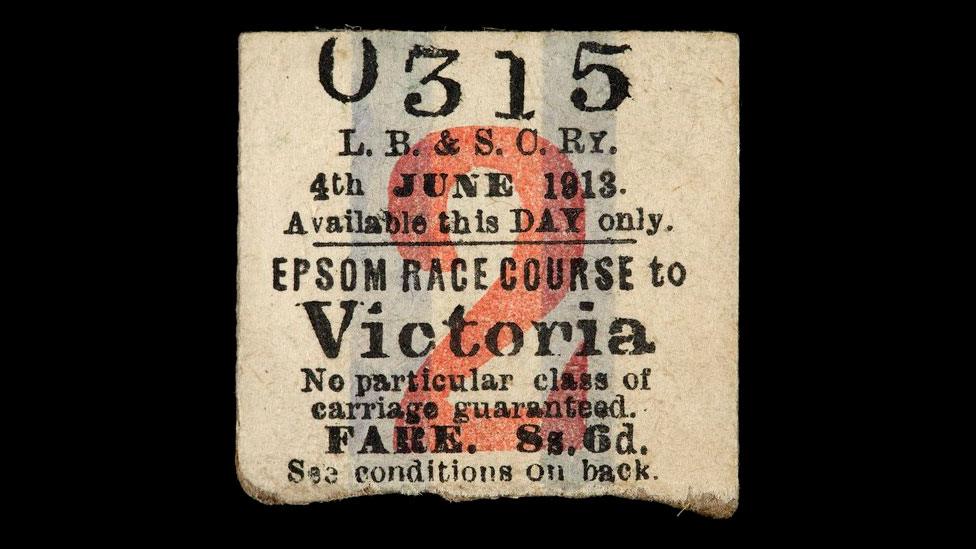

Return ticket to the Epsom Derby

On 4 June 1913 suffragette Emily Wilding Davison was fatally injured at the Epsom Derby when she ran out in front of King's horse, Anmer.

Her purpose was unclear and remains shrouded in mystery. The fact she bought a return rail ticket has been widely cited as proof she did not set out with the intention of killing herself - although research has since indicated that on Derby Day it was impossible to buy a single ticket.

But she was also planning to attend a dance that evening and go on holiday shortly afterwards.

Some historians suggest that perhaps she was attempting to draw attention to the Votes for Women campaign by tying a suffragette scarf to the horse's bridle. She was found to have such a banner tucked inside her coat.

She was knocked to the ground unconscious and taken to Epsom Cottage Hospital, where her friends decorated the bed in the suffragette colours of purple, green and white.

She died four days later.

A coroner recorded the cause of death as a "fracture at the base of the skull caused by being accidentally knocked down by a horse through wilfully rushing on to the racecourse at Epsom Downs Surrey on the 4th June 1913 during the progress of a race".

Ten days after the incident, the WSPU organised a procession that accompanied Davison's coffin through London. Thousands of women clad in suffragette colours marched past the silent crowds who lined the streets. Those in black carried purple irises, those in purple held crimson peonies, and those in white bore laurel wreaths.

A plaque dedicated to Davison remains on the railings at Epsom near the site of her fatal injury

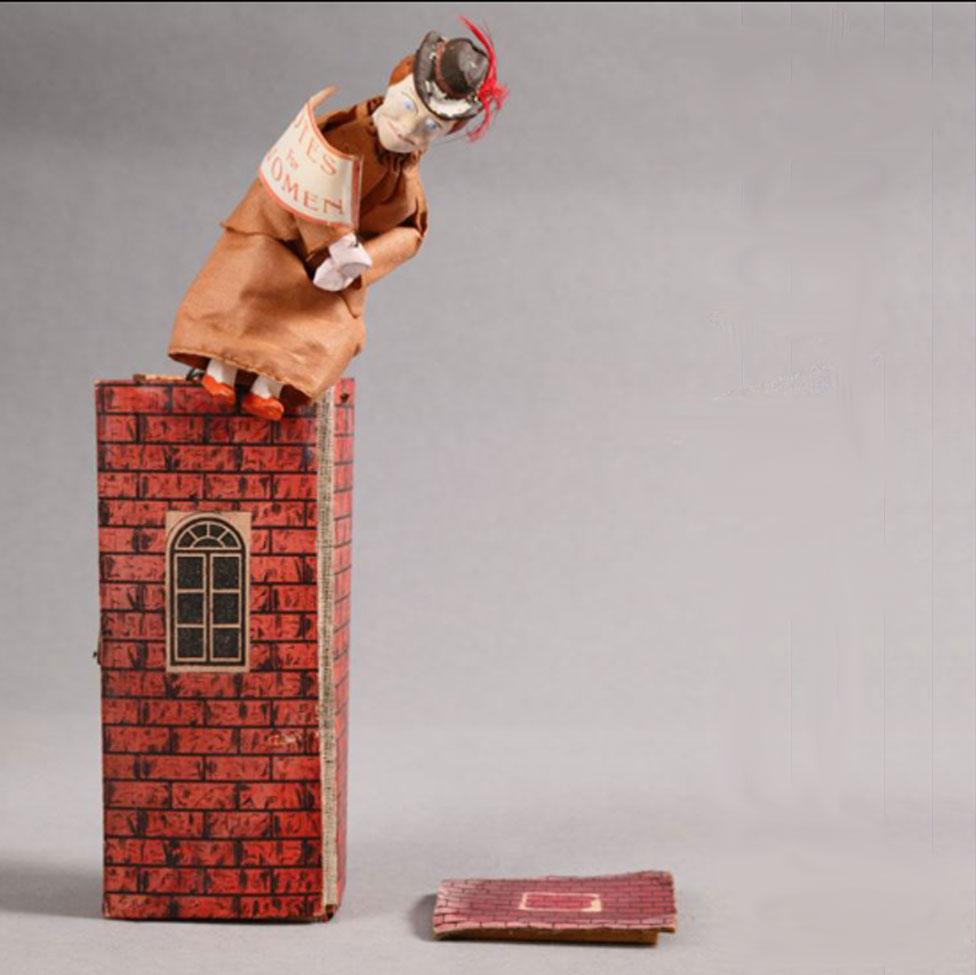

Jack-in-the-box

This Jack-in-the-box is in the form of a woman, bearing a placard saying "Votes for Women" springing out of a prison.

The toy is from the Stamford collection at the National Trust's Dunham Massey, external in Cheshire and was donated by Roger Grey, 10th Earl of Stamford.

It is one of a number of mischievous objects such as posters, postcards and playing cards that appeared regularly from about 1908 and depict the suffragette as a harridan.

The toy also demonstrates the suffragette had become a recognisable figure, worthy of caricature.

The suffragette organisations worked hard to counteract the perception of them as dowdy harridans and urged their members to emphasise their femininity by dressing their hair stylishly and wearing attractive clothes during demonstrations and protests.

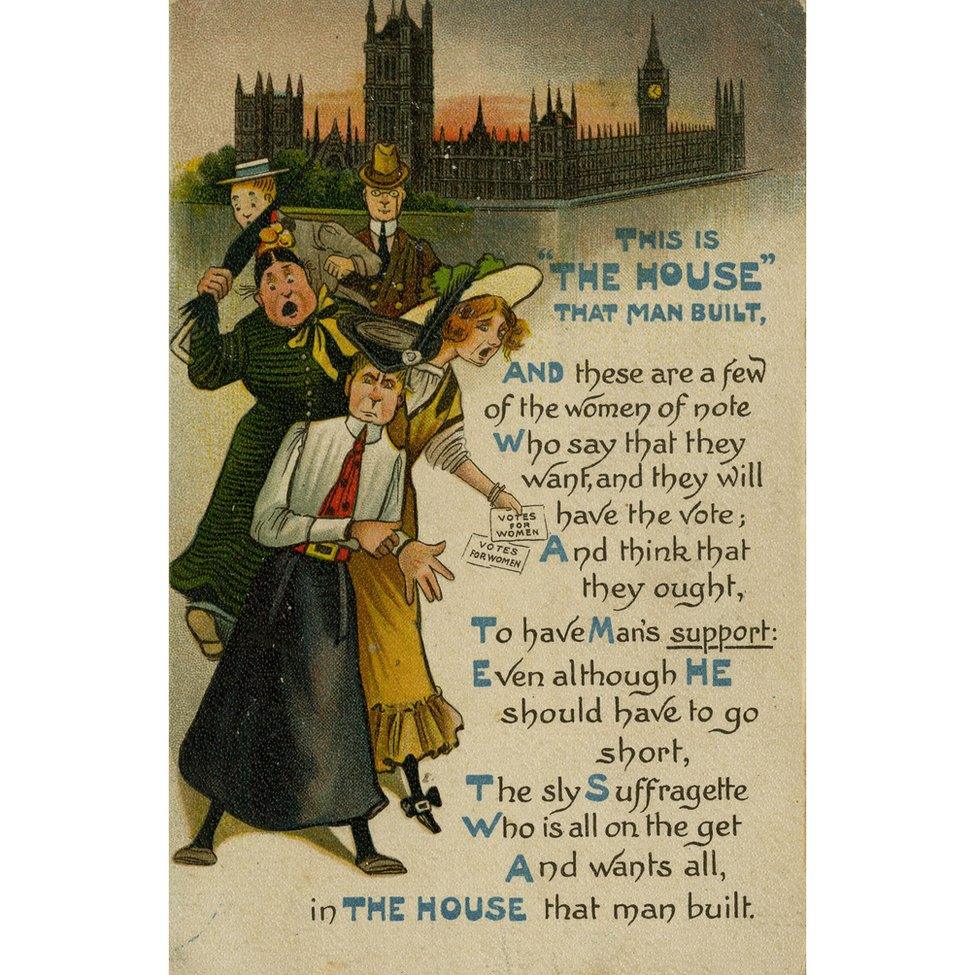

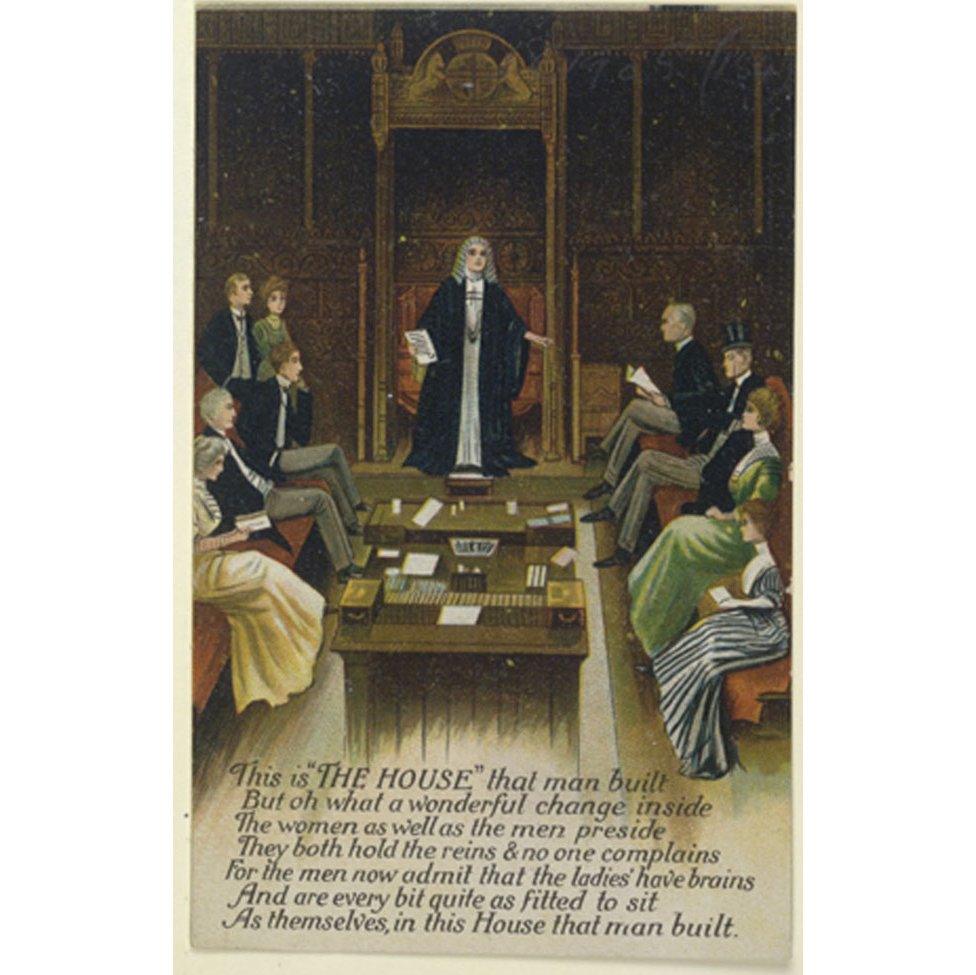

Postcard

Postcards were a useful propaganda tool for the women's suffrage campaign - but also for those who opposed it.

Perhaps most influential though, was the fact that they proved to be a financial boon for commercial card companies, which rushed to cash in on the trend to ridicule women.

The one above dates from about 1910 and is from a set of six anti-suffrage cards based on the children's rhyme "This is the house that Jack built."

The verse, changed to "This is the house that man built" refers to the Houses of Parliament.

The one below is in response to the caricature-style cards and, also plays on the house-building theme. This time though, women are inside Parliament and "the men now admit the ladies have brains".

Anti-suffrage badge

People of both sexes were against women getting the vote. The Women's National Anti-Suffrage League was established in 1908, before merging in 1910 with the Men's National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage to form the National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage.

Reasons given for this opposition were many and varied, including:

Women were creatures of impulse and emotion, incapable of making a sound political decision

Women's participation in politics would extinguish chivalry

If women became involved in politics, they would stop marrying, and having children, and the human race would die out

A woman's place was in the home

Men and women had different spheres

Women were already represented by their husbands

Women did not fight in wars to defend their country

It would be dangerous to change a system that worked

Women did not even want the vote

Mary Humphry Ward, a novelist, was the first president of the anti-suffrage league, and argued the case against women's suffrage at debates at Newnham and Girton colleges, Cambridge. Once considered a role model for educated young women, she received a hostile reception from the students when she told them that the "emancipating process has now reached the limits fixed by the physical constitution of women".

John Sutherland, the author of Mrs Humphry Ward: Eminent Victorian, gives three reasons for her decision to oppose women's suffrage: "A horror of militancy, a fear that women might look ridiculous as political figures, and a tendency to be easily flattered by powerful men such as the ones who persuaded her to take part in this exercise."

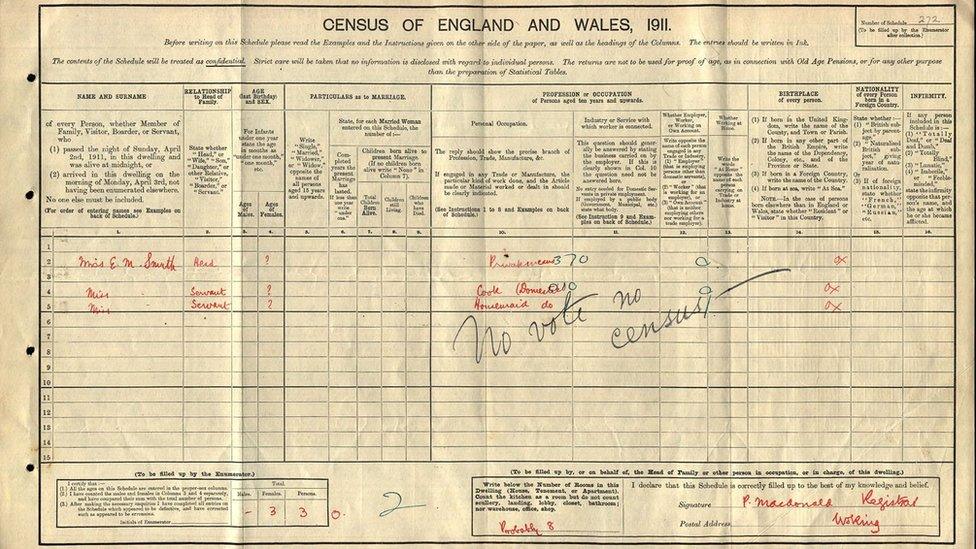

Spoiled census form

The householder Ethyl Smyth, wrote "no vote no census" across her form

In 1911, one of the main campaigning organisations, the Women's Freedom League, urged women to boycott the national census. They wanted to do something that would have an impact on the government but would not be difficult for women to achieve.

On census night, 2 April 1911, thousands of women staged a protest by spoiling their census forms or staying away from their place of residence. Many wrote across their census schedule "No Vote, No Census", and others improvised with "I don't count so I won't be counted."

In Chelmsford, a Dorothea Rock proclaimed "in the absence of the male occupier, I refuse to fill up this census paper as, in the eyes of the law, women do not count, neither shall they be counted" while another remarked "If I am intelligent enough to fill in this paper, I am intelligent enough to put a cross on a voting paper." A Miss Davies in Birkenhead completed her census form by giving the name of a male servant and adding "no other persons, but many women".

Women also spent time away from home, hid or gathered at the home of another census resister or went to overnight events, which were held in Cardiff, Bristol, Liverpool, Ipswich, Cheltenham, Reading and Maidstone, and on Wimbledon Common, where women spent the night in horse-drawn caravans.

Afterwards, the satirical magazine Punch joked: "The suffragettes have definitely taken leave of their census."

BBC Local Radio will sharing stories of these and other women from 6 February using the hashtag #1918 women. .

- Published22 January 2018

- Published6 February 2018

- Published2 February 2018