The woman who gave birth to rabbits (and other hoaxes)

- Published

"Your typewriter is hilarious!" "No, no, your cigar is side-splitting!"

If you're determined to pull off an elaborate hoax, top tips would seem to include: Be bold, be dedicated - and don't wait for 1 April.

But while pulling the wool over the eyes of the general public is one thing - such as the Panorama spaghetti crop hoax of 1957, external - tricking the experts takes another level of cunning.

The following people, who among them fooled doctors, scientists, the Royal Navy and historians, deserve a special mention.

Breeding like... rabbits

Fifteen bunnies later, Mrs Toft began to regret her passionate evening with Peter Rabbit

Unlikely as it sounds, in the 18th Century a woman called Mary Toft convinced doctors she had given birth to rabbits. Yes, doctors. And yes, rabbits.

Mrs Toft, a servant from Godalming in Surrey, surprised her family by going into labour. Even more surprisingly, she produced something resembling a kitten.

Her explanation was rooted in the long-discredited theory of "maternal impression", external - caused by being startled by a rabbit in a field in 1726 . From that moment, she said, she dreamed about, and had a "constant and strong desire" to eat, rabbits.

An obstetrician named John Howard, who seems to have been less than rigorous with his examinations, was convinced by her story. He wrote to some of England's greatest doctors and King George I, informing them of the miraculous births - including the momentous occasion when his patient produced nine dead bunnies.

The King sent his doctor to investigate. The medic, who arrived when Mrs Toft was in labour with her 15th rabbit, was certain she was genuine - and took some of her offspring back to London to show the monarch and Prince of Wales.

A surgeon was then sent by the royal household to have a look. The surgeon, apparently more sensible than the others, examined the rabbits and found that dung inside one of them contained corn - proving it could not have developed inside Mrs Toft's womb.

Meanwhile, Mrs Toft was busy giving birth to other unusual things, including a cat's legs and a hog's bladder.

Medical opinion was divided - until a man was caught sneaking a rabbit into Mrs Toft's room.

She was eventually forced to admit she had manually inserted the dead rabbits and then allowed them to be removed as if she were giving birth.

The hoaxer was later charged with fraud and imprisoned. She spent a few months in prison then returned to relative obscurity.

As for the King's doctor - he met an unhappy end after being convinced by the scam. He published a pamphlet called A Short Narrative of an Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets but after the ruse was exposed, he lost favour with the court and died a pauper.

A true gift horse

Actual photograph of Reaper, the Trodmore winner

They say the bookie always wins - but in 1898 a mystery syndicate managed to gammon the establishment and make themselves a tidy sum with an audacious scam.

The Sportsman, a leading racing paper, was contacted by the Trodmore Hunt Club to tell them of the August Bank Holiday meeting at Trodmore Racecourse in Cornwall. All the information generally provided by racecourses - rules, purses, the names of patrons, stewards, sponsors and officials - were provided.

The racecard was a good one, and a man calling himself Mr Martin, from the Trodmore Hunt Club, said he would telegraph the results to the office. The Sportsman printed it.

Bookmakers took bets as usual, and when the results came through punters collected their winnings. The following day, rival newspaper The Sporting Life printed the results after seeing them in The Sportsman.

However, there was a discrepancy in the odds given on one of the winning horses, called Reaper. The Sportsman had it down as 5-1, while Sporting Life had it at 5-2.

The newspapers needed to check which was correct, so tried to contact the racecourse.

At the same time, bookmakers were suffering after having to pay out on Reaper - a horse nobody had heard of. Some of them started to investigate its pedigree.

It emerged that there was no such place as Trodmore, let alone a racecourse. The people behind the hoax had made themselves hundreds of thousands of pounds by betting on non-existent horses, in non-existent races on a non-existent track in a non-existent village.

They were never caught.

You might also be interested in:

A Woolf in sheik's clothing

Virginia Woolf (far left) and her merry band of posh pranksters managed to annoy the Admiralty - and presumably, the Abyssinians

When not pioneering the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device, Edwardian novelist Virginia Woolf and her Bloomsbury chums were not averse to a practical joke.

In 1910, a telegram was sent to HMS Dreadnought which was then moored in Portland Harbour, Dorset. The message, purportedly signed by the Foreign Office, said the ship must be prepared for an imminent visit by a group of Abyssinian princes.

Six of the jesters turned up and despite their crude costumes of turbans and beards glued to their chins, the "princes" were welcomed with an honour guard and given a 45-minute tour of the vessel.

Soon after they left, some of the sailors began to have doubts about the "Abyssinians". One of the officers reported that he thought the "interpreter had a false beard".

The following day, the ringleader of the trick, Horace de Vere Cole, pranced into the Foreign Office and told them of the hoax.

He also contacted the press. The Daily Express reported with barely-disguised glee on how "the 'princes' were shown everything - the wireless, the guns and the torpedoes, and at every fresh sight they murmured in chorus 'bunga bunga'".

For a few days the navy was something of a laughing stock. Sailors were greeted with cries of "bunga, bunga" wherever they went.

The Admiralty was embarrassed and annoyed, and wanted the posh pranksters to be prosecuted - but as they had broken no laws, the issue faded.

The story of the hoax continued to resonate, nowhere more so than in the navy itself. The mocking phrase even ended up in a Portland music hall song:

"When I went on board a Dreadnought ship,

"Though I looked just like a costermonger,

"They said I was an Abyssinian prince,

"Because I shouted Bunga Bunga.".

Of the group, only Cole, who sounds exhausting, continued to revel in such japes, external.

Ruffled feathers

"Just. Look. Natural."

The Hastings Rarities affair was a long-running ornithological fraud eventually exposed by a statistician.

A taxidermist called George Bristow was a dab hand at stuffing birds. His glass-eyed aviary was used as a register of the birds that had been found in Hastings and its surroundings, leading to their inclusion on the official list of the British Ornithologists' Union. An extraordinary array of rare species of birds was reported from a very small area in a very short time.

Between 1892 and 1930 Mr Bristow had stuffed more rare birds, external than all other British taxidermists combined. It was later believed he had succeeded in his deception by importing frozen birds from other countries and claiming they were found in his neighbourhood.

It wasn't until the August 1962 issue of British Birds magazine that the fraud was exposed. John Nelder published his article A Statistical Examination of the Hastings Rarities, external which led to many of the birds being removed from the official list.

However, Mr Bristow may have known what he was on about - as eventually almost all of the expunged birds were readmitted to the list after they were genuinely proven to be in the country. Although not all in Hastings, all at the same time.

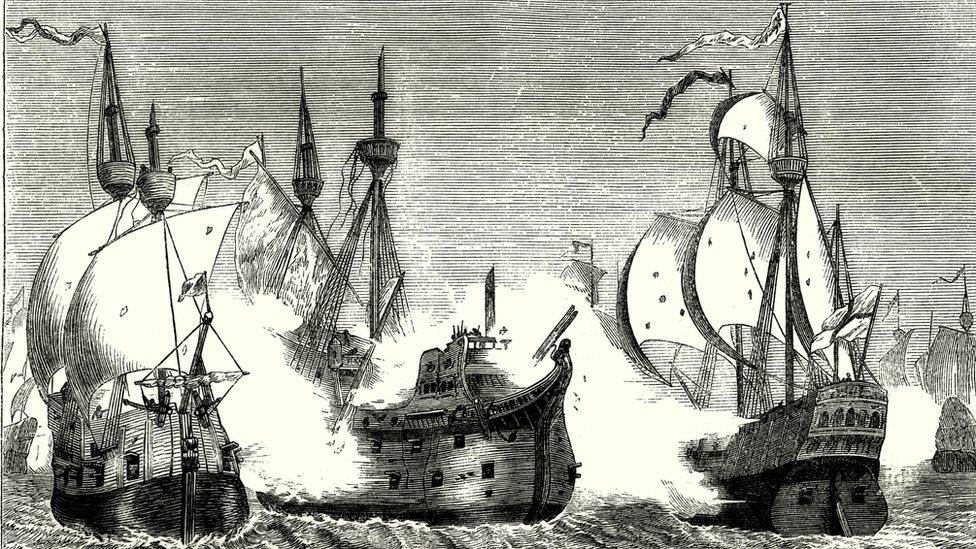

Missed the boat

Don't tell the Library of Congress

The very first newspaper to have existed was a German publication issued in 1594 - but in 1776 an English historian, Dr. Thomas Birch stirred things up when he donated a bundle of documents to the British Museum with no explanation of their origin or context. Included in the bequest was a manuscript and two printed copies of The English Mercurie, dated 23 July, 1588.

It contained an account of the English battle with the Spanish Armada. The typeset and archaic spelling led people to accept the document as real.

Its existence remained unquestioned for 60-odd years. Then in 1839, the keeper of printed books at the British Museum, Thomas Watts, came upon the original manuscript in the archives. He compared it to other examples of Dr Birch's correspondence and recognised the handwriting as that of Birch's friend Philip Yorke, second Earl of Hardwick. The two had apparently created The English Mercurie as a literary game.

However, although the hoax was debunked nearly 200 years ago, copies of the Mercurie are still mistakenly referred to as factual accounts - and both the National Library of Australia, external and the Library of Congress, external have it catalogued among historical documents from the Tudor and Stuart periods.

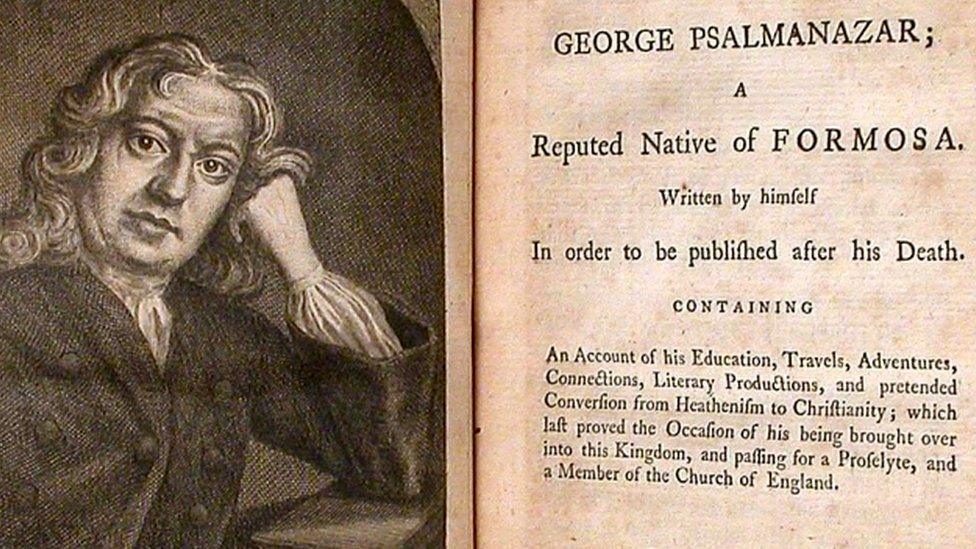

Made in Taiwan?

"I eat wives and snakes, you know. Underground."

George Psalmanazar, a blond-haired man with blue eyes, convinced English intellectuals of the 18th Century that he was the first native of Formosa - modern day Taiwan - to visit Europe. His accounts of life on Formosa were popular with London society and he was persuaded to write a book about his "homeland".

He spoke in Latin and claimed men in Formosa wore nothing but a metallic disc to preserve their modesty, that husbands were allowed to eat their wives if they were unfaithful, and the hearts of young boys were sacrificed to the gods every year. A healthy Formosan breakfast involved chopping the head off a viper and sucking its blood out.

He was invited to speak at public events and was also questioned by Edmund Halley - he of comet fame - at the Royal Society. The eminent astronomer disbelieved Psalmanazar's tale, and asked questions designed to expose him.

Undaunted, Psalamanazar replied to them all with a flamboyant insouciance, seemingly having an explanation for everything. When asked why his skin was so pale, he said he was a member of the Formosan aristocracy which lived underground.

Psalmanazar never revealed his real name or where he was from - although in his memoirs, which were published posthumously, he admitted his persona and background were entirely made up.

His books - An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, and Memoirs of ****. Commonly known by the name of George Psalmanazar; a reputed native of Formosa - are both still available in several languages.

- Published13 September 2019