London killings: Why are they happening and what can be done?

- Published

Flowers at the scene of Tanesha Melbourne's death

Another day, another death. Another headline about someone being killed in London.

On the first Monday of this month, Tanesha Melbourne, 17, died in her mother's arms after being shot in Tottenham. On the Tuesday, 16-year-old Amaan Shakoor died after being shot in the face in Walthamstow. Wednesday saw Israel Ogunsola, 18, stabbed to death in Hackney. Three more names to add to the grim litany of fatalities in the capital. Three more bodies in the mortuary.

Why is it happening? The BBC asked those who are dealing with the consequences of the epidemic of violence for their insights.

'Until you've killed someone you'll just carry on'

Nequela Whittaker used to be a gang leader in south London. Now she's a youth worker.

"The youth culture seems to be falling apart at the moment. Young people don't feel like they fit in with society and there doesn't seem to be a voice for young people so at the moment there's a bit of carnage. On the streets it seems to be feuds from social media, from gang rivalry, postcode wars. At the moment it seems to be an epidemic of violence between the young people and it's getting worse.

"It's a discussion and conversation we need to have, to address what's happening and think what the community is doing.

"What is it that young people are lacking - what can we do? what opportunities can we create for young people?

"They feel that this is the life they are accustomed to - but there is a lot more out there and we need to find out what will keep them motivated.

"Due to spending cuts there has been less policing, community centres are closing. There's been not money directed at the third sector for a while and with all these cuts and reductions we've got more young people falling out on to the streets.

"Young people argue on social media over nothing. A boyfriend or girlfriend is in a feud and it escalates and you get people getting involved in situations that didn't necessarily involve that young person first hand.

"Young males are coming from homes with no fathers, no male role models. Many are lacking love.

"At the moment there are a lot of parents trying to be their children's friends rather than being the authoritarian person in their lives. When it comes to the stage of trying to impose discipline it's too late and the young person is 15 and has learnt their own way of life.

"I've got to be honest - looking back at my mindset when I was 15 or 16 - nothing would have stopped me.

"Until you've either killed someone or it's you in that body bag you're just going to get a Youth Referral Order and you'll just carry on."

'You get the society you deserve'

Martin Griffiths is a consultant surgeon at Barts Health NHS Trust in London.

"We've seen a real sea change over the past few years, with a significant increase in the number of people who have been injured, in the number of injuries sustained per person, and the severity of those injuries.

"The youth of many of the victims and the assailants is really, really concerning. Back in the 1980s, we looked at interpersonal injuries involving knives and guns as being relatively uncommon - a niche injury. Now it's our core work. Knife and gun injury is most of what we see. We're performing major lifesaving surgery on a daily basis.

"One of my military colleagues has described the situation as like being at Camp Bastion [in Afghanistan], which is really worrying to hear.

"And we routinely have children in our care. Thirteen, 14, 15-year-olds coming in with knife and gun wounds is a daily occurrence. We used to look after people in their 20s, now children in school uniforms are being admitted.

"Some kids are involved with gangs or in the drugs trade, but more often than not it is that young people with poor impulse control who've been put into difficult situations and who don't respond well to conflict.

"I think young people are easily swayed and the lack of positive role models, mentorship, and support for young people feeds into them being led down the wrong path.

"We've seen a normalisation in attitudes toward violence globally - and also we take offence about pretty much everything. If we look at people now - things escalate on social media now about absolutely nothing. People now, when placed in conflict situations, react in a much more expressive manner. And if people who are running countries react in that manner, it's a signal for everyone to react that way.

"Members of the public who are not involved in gangs or violence let these things pass without comment. You get the society you deserve. If you ignore violence and ignore offending as a member of the public, your society will change.

"We are all responsible for what is happening right now."

'Each community centre has a gang'

Police say Jamel Boyce was involved in a "minor scuffle" before the stabbing

Patrick Boyce's son Jamel was aged 17 when he was stabbed in Clapham in 2016. He is now in a semi-vegetative state and will never recover his brain function.

"It's a new game for the teenagers; running into one area and stabbing or shooting someone in that area and then going back to their own area. Then someone from that area will go to the other area and stab or shoot someone else.

"The tragic thing is that those they're stabbing or shooting are just innocent people who accidentally live there.

"My son was attacked after he came from college. He got stabbed in his leg and stabbed in his heart. He knew the attacker; they used to go to the same college.

"My son didn't carry a knife and he wasn't in a gang, he was just going out on the Friday afternoon after college with his friends and he got into an argument with somebody. That guy decided he wanted to kill my son. Just like that.

"These kids come from dysfunctional families, often single parents with no father around and the mother might be working 14, 16 hours a day.

"They come home and there's nobody there, so the streets become their family. They find comfort in each each other. Schools are letting them down, families are letting them down. Then they perceive that being in a gang makes them stronger, that it makes them somebody. It's a negative path for any teenager to think that is the only future they might have.

"Social media does play a part but social media does not make a teenager pick up a knife and go out on the streets with it.

"I think it's good that cuts mean community centres are closing, otherwise community centres would have more murders. Each community centre has a gang and they are going to attack each other.

"We need to get these children into a position where they can see a future, an option rather than saying they are going to pick up a knife or gun and sell drugs. And it's all down to drugs, they're killing each other because they're selling drugs."

'It doesn't bode well for us this summer'

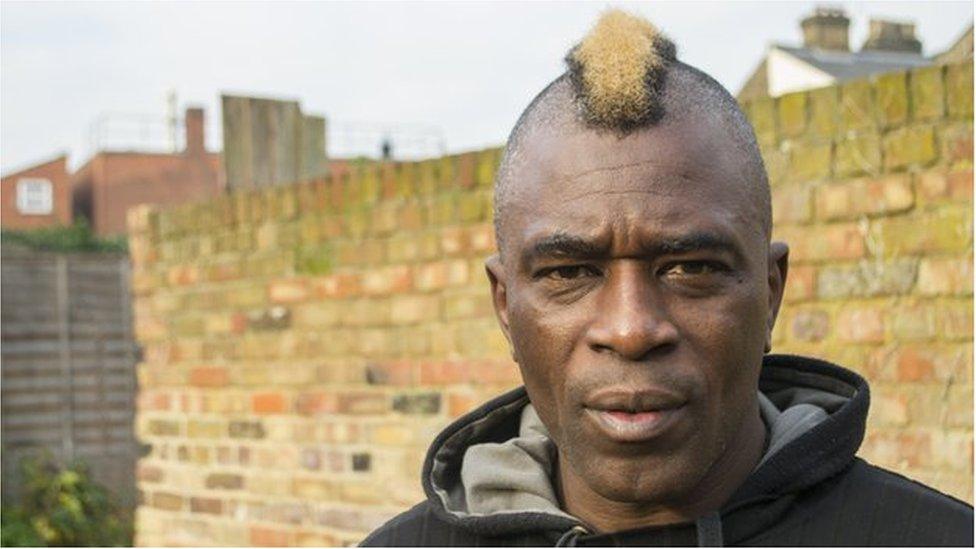

Ken Hinds is the chairman of Haringey's Independent Stop and Search Monitoring Group.

"Stop and search, external is playing into the hands of the violence. It needs to be used with caution or we are going to alienate the very community that is being affected disproportionately by this violence. We will alienate them into not giving intelligence to the police so they can actually find knives and guns on our streets.

"In the Haringey community what's happened now is that if you shoot me or one of my people, I am going to shoot one of your people.

"It doesn't bode well for us for this summer.

"I think we need a curfew in place for those aged 21 and under between 9pm and 7am to get a grip of what's going on across the hotspot areas, particularly in north London - the high-crime areas where the murders are happening.

"We ought to have some sort of respite and think outside the box. So if you've not got a good reason to be on the street and you're just hanging around, you should be in your home. What happens is that big groups hang about on the street or in McDonald's intimidating people. The police can't do much; if they move them on they group just goes elsewhere.

"Lots of people are not being guided, or they are being misguided. In these situations violence will happen."

'The policy of austerity'

Anthony Gunter (inset) researches gang violence

Dr Anthony Gunter, a criminologist from the University of East London, has written a book Race, Gangs and Youth Violence.

"The young people I spoke to felt that the gang problem was a media invention, it didn't speak about the realities of their daily lives. They believed the causes of youth violence included bad parenting, lack of youth centres, poverty, the media and status.

"They also talked about the need to have 'back-up', and the protection that comes from moving in a big group of friends. To them their experiences in their neighbourhoods represented a place of constant risk and danger. Young men in particular had to be vigilant against the constant threat of violence and robbery.

"The government has made the fatal error of assuming that all violence among young people in cities is caused by gangs. But the evidence for that is extremely thin, and much of the data that does exist is distorted, external, London-centric, and contrived from unverified police intelligence sources and the opinions of a small group of justice professionals and senior police officers.

"The policy of austerity has had an especially large impact on those young people most affected by knife and gun violence. They no longer have access to the Educational Maintenance Allowance, external, Connexions Careers Service or housing benefits, and youth support services have been decimated. Those fortunate enough to get into university have seen tuition fees tripled, while maintenance grants for students from poorer backgrounds have been scrapped.

"The teenage years are associated with risky and problematic behaviours for everyone. But these behaviours are aggravated by poverty, inequality, school exclusions, mental illness and chaotic family circumstances. Rather than thinking of violence among young people solely as a crime problem, it should be considered a health risk, alongside drug use, smoking, drinking and unprotected sex.

Then it becomes clear: the way to respond to stabbing deaths among young people is to improve their life chances and opportunities, by investing in education, health and welfare services for all.

'It is entirely predictable'

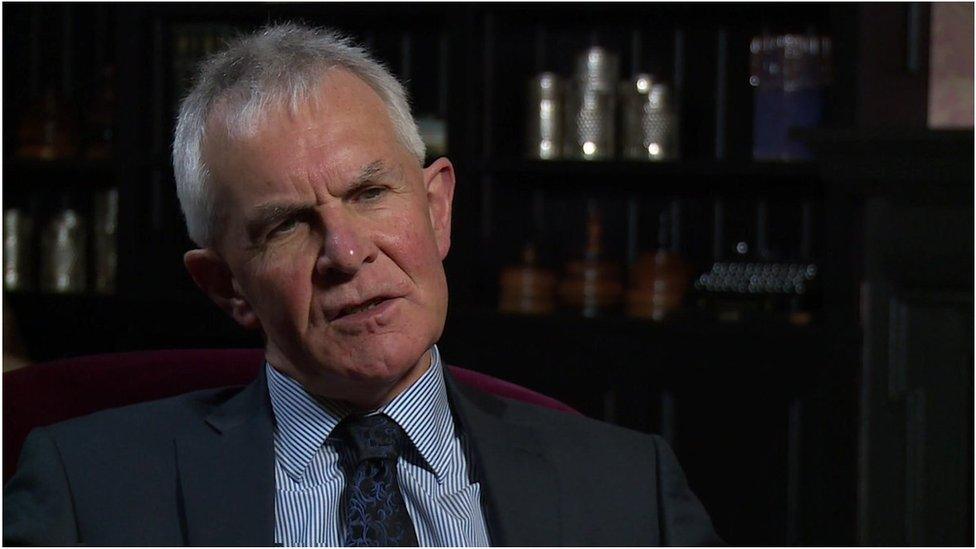

Sir Peter Fahy is a former Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police

Sir Peter Fahy tackled violent crime during his time as Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police. He has said the police service was "being cut in half" due to central government spending changes.

"There's a very strong link between young people excluded from school and those who end up as offenders, often violent offenders.

"When you look at the background of most of those convicted of violent crime - sadly it is entirely predictable.

"In certain districts where there is a high level of criminality, there's a high level of social deprivation.

"In this country it's very rare for a stranger to be shot or a shooting in a robbery situation, most of it is between people with some sort of criminal association or when you get young lads involved in street gangs when they fight across territory. You see people getting shot dead for the most stupid of reasons.

"It can only be cured by good local intelligence-led policing and working with faith groups, churches, schools and community groups."

Under the Conservative and coalition governments, the number of police officers has fallen by somewhere between 19,000 and 22,000.

The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Cressida Dick, said she was talking to the government about reconsidering future funding. In response, the Home Office said it was "undertaking a period of detailed engagement with policing partners and relevant experts".

- Published16 April 2018

- Published4 April 2018