English identity: Your questions about patriotism

- Published

How English do you feel? Views from Hackney and Boston

Why doesn't England have its own national anthem and why are the English obsessed with tea? These are some of the questions our readers asked about English identity.

English vs British

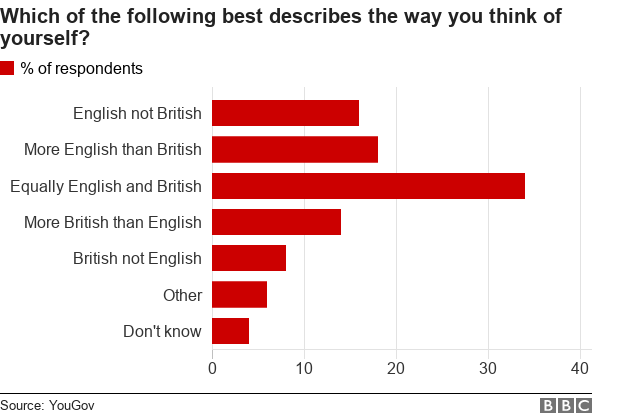

Jacqueline Le Sueur wanted to know if the people surveyed thought of themselves as more English or British.

Eight out of 10 people in England identify strongly as English, a survey of 20,000 people found.

But Jacqueline Le Sueur, 57, from North Devon, was one of a number of readers who wanted to know whether those surveyed thought of themselves as more English or British.

"I always search for the way on a form to say I am English rather than British - ironic given that I am an absolute supporter of the Union and would hate to see it dismantled, and am an equally strident European," she said.

"I am really intrigued to know how the English think of themselves when asked nationality."

Another reader, James Buckler, 34, from Birmingham said the first time he sent off for his passport he wrote his nationality as English but was confused when it came back as British.

"I remember feeling a sense of shame and confusion for not knowing my own nationality. I felt like I had gotten it wrong," he said.

Across England, just over a third of people surveyed saw being English as more significant than being British, with 16% saying they were English, not British and 18% feeling more English than British.

Just over a fifth, 22%, consider themselves either more British than English or completely British and not English.

Dineo Masiane said she identified as British and not English

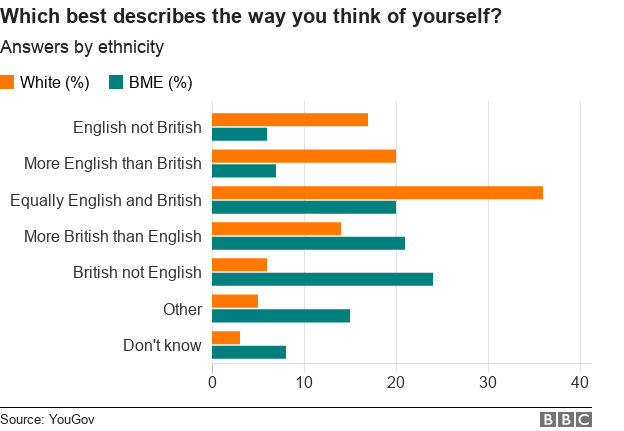

A number of readers asked to see a comparison of how people from white and BME backgrounds identified themselves as British or English.

Among black and minority ethnic (BME) respondents, the proportion identifying more as British rises, with 24% saying they were British and not English.

Dineo Masiane, 20, was born in Zimbabwe and said she would call herself British rather than English because "it's down to ethnicity as well as where you were born."

"I feel like if you did say you were English you would get a lot of backlash for that," she said.

"It goes back generations. When you see old portraits you see people with fair skin, you don't see black people there."

Kehinde Andrews, associate professor in sociology at Birmingham City University, said the "vast majority of black people would not say they were English."

"They might say black-British," he said. "But not Black English because Englishness is something that is associated with being white."

Michael Kenny, professor of public policy at Cambridge University, said: "It is still the case that a majority of black and Asian people prefer to identify as British, which retains a more inclusive, civic feel, than English.

"But there are signs too that this pattern may well be changing in different ethnic communities and among younger generations."

Patriotism vs nationalism

Roy Williams in Stoke-on-Trent has covered his house in over 40 England flags in preparation for the World Cup.

"Why are all the home nations, except England, allowed to be patriotic?" asked one reader, who wanted to be anonymous.

Prof Kenny said there was an idea that the English are not permitted to be proudly patriotic, in the way that the Scots, Irish or Welsh are.

He said it was an anomaly with a long history and rooted in a belief that the nation is a unified political entity but continues to governs far-flung territories.

Prof Kenny believes that change is afoot.

"The complaint that the English are not allowed to be patriotic "flies in the face of a considerable body of evidence, external that a growing number of English people have, in the last two decades, begun to develop a more unabashed pride and interest in their own English identity - and not just when the World Cup comes around."

The flag has been adopted by far-right groups over the years

Sue Taylor, 52, from Lancaster said: "I identify strongly as English but feel our flag has been hijacked by racists or undesirables. How do we reclaim our flag?"

Reader Sebastian Gallop asked: "What do people have against the St. George's Flag? How can people think that a flag that's represented this country for centuries be racist?"

The English flag bears the cross of St George and can be traced back to the middle ages but was adopted in the 1970s by far right groups.

Prof Andrews said it subsequently became associated with racial tension, much like the Confederate Flag in the southern US states.

"Historically it's been associated with the National Front, British National Party, English Defence League. It's come to represent far-right, exclusive, white nationalism," he said.

"Unless it's the World Cup it's still got that imagery."

Prof Kenny believes that over time, the flag has come to acquire a wider set of cultural associations and has been reclaimed on the part of many ordinary English people.

"Since its first appearance as a mass phenomenon at the Euro '96 football tournament, it has become a part of our cultural wallpaper, appearing on mugs, t-shirts and flip-flops."

Costume drama

Beefeaters wear one of the many costumes associated with England

"Why doesn't England have a national costume?" asked one reader who wanted to be anonymous.

A quick online search for an English national dress brings up an array of costumes from a Beefeaters to Morris dancers, pearly kings and queens to the England football strip.

In 2015, the then Miss Great Britain, Grace Levy from London, dressed as a beefeater , externalfor the The National Costume round of the Miss Universe pageant.

The outfit most commonly associated with England fans is that of a crusading knight. But there is no definitive traditional dress to represent the country.

Prof Kenny said Englishness has historically been more associated with behavioural norms like standing in queues and state pageantry, rather than prescribed cultural traditions or costumes.

And Dr Jenny Gilbert, lecturer in design cultures at De Montfort University in Leicester said: "Historically, English culture has dominated much of the world, meaning the need to assert national identity sartorially has not taken on such significance.

"Due to empire and cultural imperialism, English dress became the default form of dress for much of the world - just look at how the tailored suit has become the global standard for business attire.

But she argues the English have a "very distinct" form of dress marked by tensions between conservatism and radicalism.

"Tweed-clad aristocrats, tartan-clad punks, pinstriped politicians or the sportswear-clad grime artists - English fashion designers draw upon our history of great eccentrics.

"Look at the work of Paul Smith or Vivienne Westwood.

"If there was to be an English national costume - and I'm not sure we really need one - it would be something that combined these eccentricities and tensions with humour, whilst also reflecting the diversity of modern England - maybe this is a job for Grayson Perry?"

A nation of tea lovers

A nice cup of tea can cure all manner of ills in England

Wade Jones, 28, from Nottinghamshire asked this question after his near-obsessive tea-drinking was remarked upon by his international flatmates at university.

"They commented to me how much tea I drank. I love tea. It was vital to keep me going in my studies."

The English association with tea, external can be traced back to the 1600s when the British East India Company had a monopoly on the trade.

The drink saw a surge in popularity in the 1800s when Queen Victoria and her friend, Anna Russell the Duchess of Bedford, took to taking tea.

Their celebrity-like status saw tea rooms become fashionable with women and tea became a firm fixture with the nation.

It was even sent as a morale booster to soldiers during the World War Two when Prime Minister Winston Churchill declared it "more important than bullets".

Wade Jones said tea was vital to keep him going with his university studies

"Tea is still believed, by English people of all classes, to have miraculous properties," according to anthropologist Kate Fox, in Watching the English, external.

"This magical drink can be used equally effectively as a sedative or stimulant, to calm and soothe or to revive and invigorate.

"Whatever your mental or physical state, what you need is 'a nice cup of tea'."

A song for England

Richard Owen, 56, said: "I always find England using the British anthem a sign of 'English arrogance' from the past, assuming all British people relate to England.

"I am Welsh and so revel in our national anthem when it is played and the sense of national identity and pride that it engenders. England should have [William Blake's] Jerusalem, or something like that."

At international cricket matches William Blake's Jerusalem is played as the team runs on to the field

Mr Owen is talking about how the English sing the British national anthem at sporting events and ceremonies.

Prof Kenny said it showed "the way in which the British and English national identities have been so deeply intertwined over the last few centuries".

The idea of a dedicated anthem for English sporting teams has become a topic of growing debate, external in recent years, he said.

He said it represented "a feeling among many English people that their own national culture and sense of identity needs greater recognition".

Mr Owen's suggestion of Jerusalem - which includes the lyric "England's green and pleasant land" - joins others such as Land of Hope and Glory, I Vow To Thee, My Country and There'll Always Be an England.

The English National Anthem Bill 2015-16, external got no further than the first reading in Parliament. So until a bill is passed, the English will continue to sing God Save The Queen.

- Published3 June 2018

- Published13 January 2016

- Published13 January 2016

- Published23 April 2019

- Published5 June 2018