George Ormond case: A hidden tape recorder helped catch my abuser

- Published

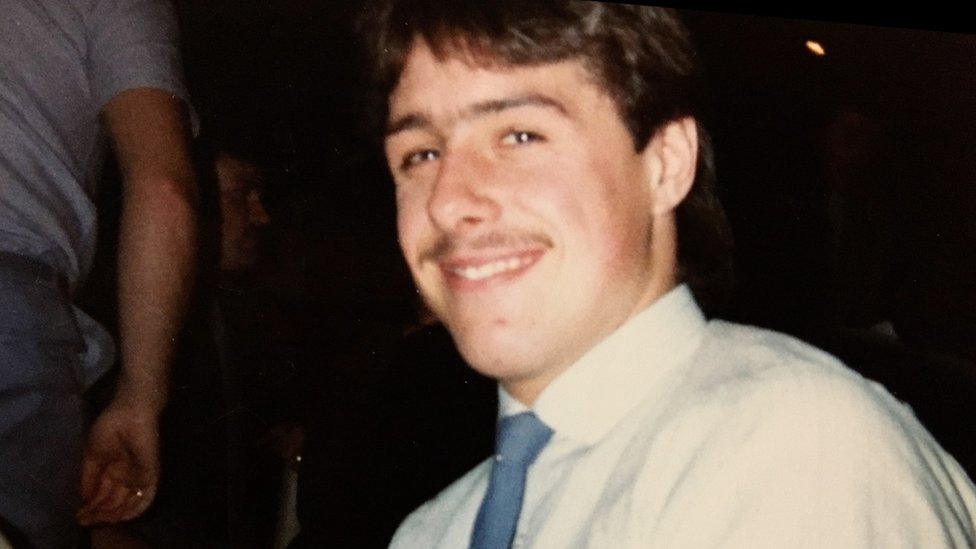

Derek Bell says as a child he was "scared" of telling anyone, including his family, about the abuse

When former footballer Derek Bell saw the coach who abused him as a child, waiting outside a hostel for teenagers in Newcastle, he went into a fit of rage - taking a knife to the man's house and kicking his door down.

His abuser, George Ormond, wasn't at home. But what happened next led to Ormond's jailing in 2002, and now a second conviction for sexual abuse against another 18 young victims.

"It was full of damp, the ceilings were leaking, it was very run down. But that's where it first started, the touching on the treatment table," Derek Bell tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

Before a career-ending injury, the promising midfielder played alongside the likes of Kevin Keegan and Chris Waddle at Newcastle United.

But years before that he learned his game playing for a well-known boys' club in the North East.

It was there he was abused by former coach and unofficial physio George Ormond from the ages of 12 to 16.

"He used to take us to parks in and around the West End and perform sexual acts, ask me to perform sexual acts," says Mr Bell.

He says he was too scared to come forward and tell others what happened - partly because he didn't think he'd be believed, partly because of the power and control wielded by Ormond.

"He used to say, 'Listen, if you don't perform these acts on me then I'm not going to play you. I'm going to tell the scouts that your attitude is bad and I'll not play you for months'"

Mr Bell left the team without telling anyone, even his parents, about the abuse.

Derek Bell as a young boy

Mr Bell was later signed by Newcastle, eventually playing for the first team alongside some of his boyhood heroes.

But a bad knee injury cut short his career and his dream of playing top-flight professional football faded away.

Years later, in 1996, he was working for the local council helping to rehouse and support asylum-seekers.

Staff reported a shady-looking man hanging around outside one of the asylum hostels in the west of the city.

"I remember it vividly," says Mr Bell. "We went down there, and I saw this guy with a hood hiding behind a tree. To my astonishment there was George Ormond."

"[The asylum-seekers] were coming from all over - Iran, Iraq, African countries - young, vulnerable 14-year-olds by themselves. There was only one reason why he was there."

Derek Bell worked to rehouse and support asylum-seekers for the local council

Mr Bell was struggling with personal issues at this time. He had an alcohol problem and tried to kill himself three times. At one point, he was sectioned in a psychiatric hospital for his own safety.

Some strong words were exchanged between the pair. Later Mr Bell learned that his abuser was still involved in football, now as an assistant youth coach for Newcastle United.

At the start of 1997, Mr Bell warned people working at the club, who told John Carver, then in charge of the club's youth set-up and later first team manager.

With an allegation but no solid evidence he says he could not act straightaway - Ormond was still part of the club's youth team contingent which travelled to Coleraine, Ireland, for a major tournament that summer.

Ormond finally left early the following year after Carver said he used a change in FA rules to quietly get rid of him.

12in knife

Around this time Derek Bell had decided to take matters into his own hands.

"I was insane, I was burning and had never spoken about it all these years. I just exploded and went to his home and kicked the door in," he says.

Mr Bell had a 12in knife in his pocket, but Ormond was not home.

"The way I was feeling, I probably would have killed him," he says. "I take no glory in that. I was just in a really, really bad way."

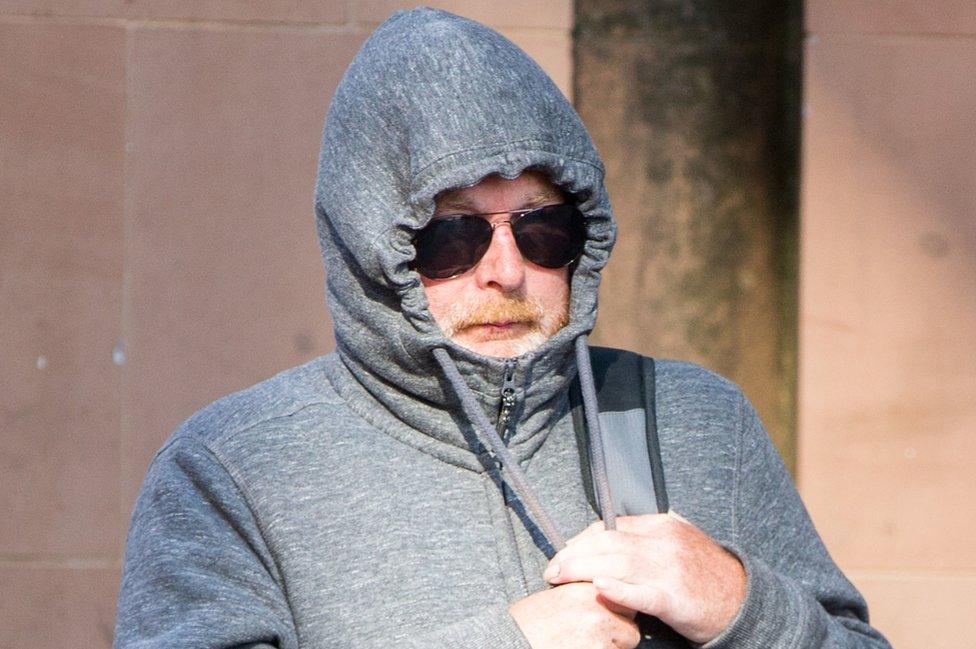

Ormond was first convicted in 2002

At his lowest point, Mr Bell finally told close friends about the abuse for the first time. He came up with a better plan.

"I went down to his [Ormond's] house, and I had a tape recorder in my pocket.

"My heart was going really fast and I asked him some pertinent questions. 'Why did you feel the need to abuse me?'

"He never said sorry, but I actually caught him on tape saying, 'Yes, I did do it.'"

Mr Bell played that tape to his friends, who convinced him to take it to the police. Ormond was arrested and stood trial for the first time, in 2002.

The tape was played to the jury and Ormond was convicted of abusing Derek Bell and six other men. All had been young boys at the time of the crime.

"I broke down and cried when the verdict was read out," Mr Bell says.

Derek Bell was abused by Ormond between the ages of 12 and 16

Ormond was sentenced to six years in prison. Judge Esmond Faulks described him as a predatory abuser of young boys who used his position as a football coach to target vulnerable young children.

But Mr Bell was always convinced there were more victims waiting to come forward.

In November 2016, he saw another footballer, Andy Woodward, speak on the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme about abuse involving a different coach.

Mr Bell, who was anonymous in the first trial, decided the time was right to speak out publicly.

He was interviewed in detail on the BBC show, he said to raise awareness and support others who might want to report similar crimes.

'Dreams in my hand'

More victims started coming forward to police, and a team of 11 specialist officers were assigned to work on the case.

In May 2017, Ormond was charged with another 38 counts of abuse against 19 boys and young men from 1973 to 1998.

The court at his trial heard how he targeted young Newcastle trainees in a residential guesthouse in the city.

He abused other boys on school trips, in changing rooms, in his van on the way to matches. He told one victim: "I have got your dreams in my hand, if you say anything I will crush them."

George Ormond arriving at Newcastle Crown Court in May

Ormond, who denied all the charges, declined to give any evidence in his own defence.

He has now been convicted of the sexual abuse of 18 young people and faces another lengthy prison sentence.

For Newcastle United, there are outstanding questions about what the club knew when, and whether more could have been done to protect young players all those years ago.

The club is making no official comment but says it has co-operated fully with the police investigation and the continuing FA probe into sexual abuse in the sport.

Mr Bell says Newcastle United were "very supportive"

Mr Bell himself has met Newcastle United representatives and describes the response as "very supportive".

Looking back he now says he regrets not coming forward and reporting Ormond to the police earlier.

"This guy was allowed to roam for 25 years and sometimes I feel responsible for that. Maybe I could have stopped that," he says.

He is now a qualified safeguarding officer and has co-founded a not-for-profit organisation, Save, along with three other former professional footballers to push for better regulation and child protection in the game.

"It's like a Pandora's box. Will I ever get full closure? Probably not," he says.

"It will always be there because it's locked in my mind, my personality. But I've learnt to cope with it now and for that I'm thankful."

Watch the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel.

- Published13 June 2018

- Published18 June 2018