Spanish flu: 'We didn't know who we'd lose next'

- Published

Hannah Mawdsley, who is researching letters by Spanish flu survivors for her PhD, found out she had a relative who was killed in the pandemic

An extraordinary archive of letters written by survivors of the Spanish flu pandemic, which paints a vivid picture of a nation gripped by fear and chaos, is helping to provide insights into life in the shadow of a killer disease.

Hannah Mawdsley, who is researching the documents at the Imperial War Museum, describes the letters as a "precious window into the human experience of the pandemic", which killed more than 250,000 people in Britain and as many as 100 million globally.

Bequeathed to the museum by historian and journalist Richard Collier, the collection was amassed in the 1970s and is comprised of about 1,700 accounts of those who witnessed the pandemic first hand.

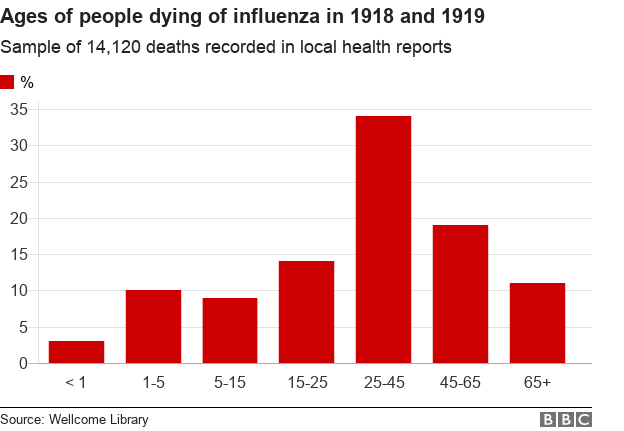

The BBC England data unit analysed medical officers' records for English districts held by the Wellcome Library to show the impact of the pandemic.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this map

Map built using Carto. Can't see the map? Tap or click here, external.

The joy of Armistice Day celebrations in London in 1918 contrasted with the misery being experienced by many

One nine-year-old girl from Coventry whose 35-year-old mother and seven-year-old sister died two days apart wrote to Mr Collier in the 1970s about the impact of the disease.

"It caused quite a sensation having to have a double funeral on November 11th 1918, which was the very day the First World War ended," she wrote.

"I can remember very well when the cortege was on its way to the church. Bells, hooters and all sounds of celebration were raving but how silent people stood who realised it was our funeral.

"It really was a terrible time, not knowing who we were going to lose next."

In what was a cruel twist of fate, Spanish flu arrived on British shores just as soldiers were returning home from the horrors of war.

"You've got harrowing stories of soldiers who've survived the war... they're on their troop ship on their way home and they get a letter to say that their wife's died," said Ms Mawdsley, a PhD researcher at Queen Mary University of London.

"There was all this celebration, joy and relief at the end of the war that collides with death and grief."

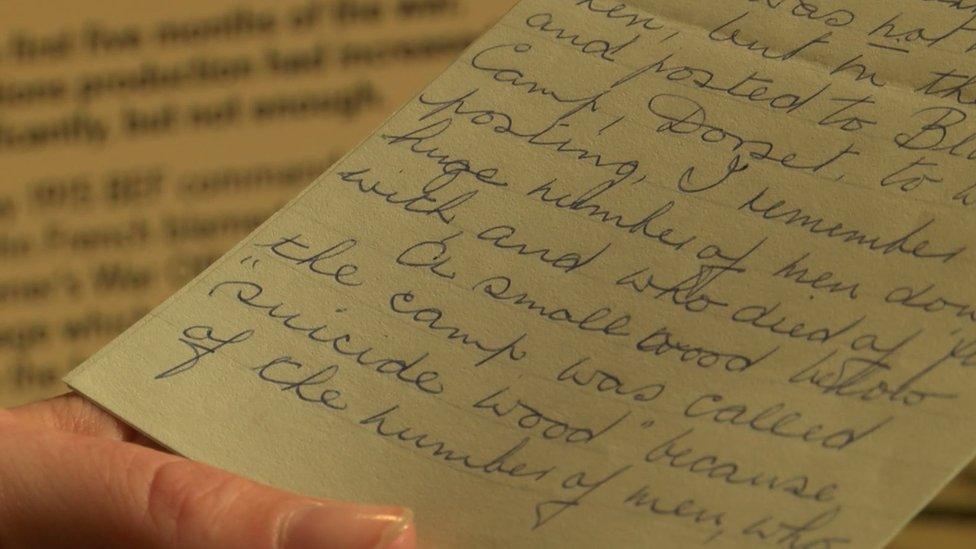

One letter told of how Spanish flu left people with "disturbed minds" - some sufferers developed a psychosis, which in extreme cases led to suicide and even murder

The young son of a Baptist minister in Leicester wrote of his father sleeping in the cemetery chapel while he conducted funerals from dawn until dusk.

He wanted to avoid taking the virus home to his wife and eight children - all of whom survived. They were the lucky ones: Leicester was hit especially hard with more people dying there in 1918 than there were babies born.

About one in every four deaths in the city that year was attributed to influenza.

"The funeral corteges followed each other through the town," the man wrote to Collier on 19 May 1973.

"Often there was more than one coffin in a hearse. Graves were used to bury more than one person, especially when more than one of a household were victims at the same time."

The letters describe Spanish flu's "spectacular" symptoms, said Ms Mawdsley.

"Some victims suffered something called heliotrope cyanosis which was kind of a creeping blue which started in your fingertips, tips of your ears and nose and lips but you could go completely black," she said.

"As it progressed you were more and more likely to die. Immediately after death the corpse would go completely black, which must have been very traumatic for loved ones to see."

The relentless processions of bodies through the streets was a sight a man from Stepney in east London could never forget.

"The undertakers couldn't make the coffins quick enough, let alone polish them," he wrote on 16 May 1973. "The bodies changed colour so quickly after death they had to be screwed down to await burial.

"The gravediggers worked from dawn to dusk seven days a week to cope. The smell of those deaths was indescribable."

RAF personnel in Dorset killed themselves in the woods due to Spanish flu, one letter said

Spanish flu also afflicted some people with a psychosis that could lead to murder and suicide. Newspaper reports detailed some of these deaths, which the courts attributed to "delirium during influenza".

A man who was in the RAF at Blandford Camp in Dorset wrote: "A small wood below the camp was called 'suicides wood' because of the number of men, who had flu, committing suicide there.

"The flu seemed to leave people with disturbed minds."

A baker from Norfolk battered his wife and two sons to death before hanging himself, according to the Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail of 6 November 1918.

"Sitch was attacked by the malady last week, and eventually the whole family were obliged to take to their beds," the newspaper said.

"Yesterday morning a neighbour discovered Sitch's body hanging from a line in the bedroom and the wife and children were afterwards found battered to death in another room. A chopper and bayonet were found in the room."

A James Sydney Shaw, 33, severed the windpipe of his two-year-old daughter Edith, according to the Aberdeen Evening Express of 26 November 1918.

"The facts were very sad because the accused was very fond of his child," it said.

"On the night of October 18 a neighbour heard Mrs Shaw call out: 'Come quickly! My husband has gone mad!' and she found [the accused] lying on the floor with a wound in the throat.

"Little Lucy... was sitting up in bed crying with blood on her. Leonard too, was crying, and poor little Edith was lying back in the bed with her throat cut."

When examined by a doctor, Shaw "did not seem to know anything about the tragedy". He was declared insane due to "delirium during influenza".

A quarter of the British population fell ill with Spanish flu at some point during the pandemic and about 228,000 people died, according to the Wellcome Library.

By contrast, the number of people who died of influenza in England and Wales in 2016 was 430.

Spanish flu "paved the way" for a sleeping sickness virus in the 1920s according to a German doctor

In places like Leicester, Coventry Felixstowe and Malmesbury, about 25% of deaths in 1918 were attributed to influenza.

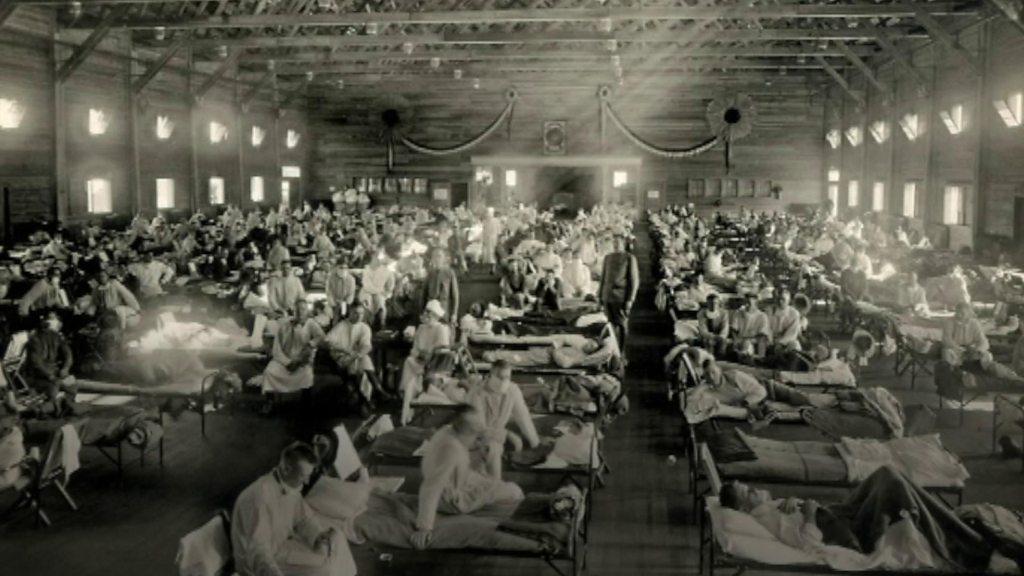

Viruses were not well understood at the time and doctors were at a loss as to how to treat people.

"'Cures' ranged from standard camphor and quinine to alcohol - whisky in particular was sworn as the cure," said Ms Mawdsley.

"But some more extreme cures like creosote and strychnine were used. Basically, people were so desperate they would try anything."

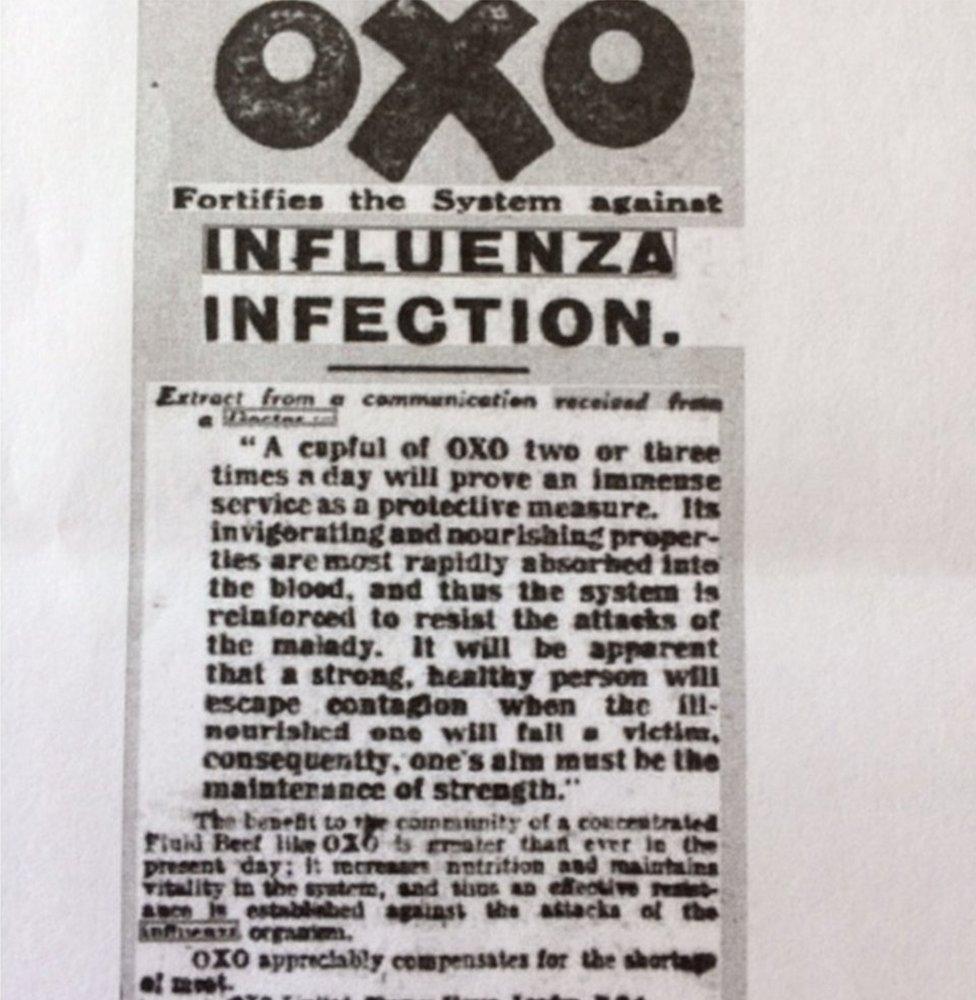

An advert in the Northern Whig in Belfast hailed Oxo gravy as an "immense service as a protective measure".

"Nursing was one of the only things that really helped and there was a big call out for volunteer nurses at this time as so many had been shipped off to the Western Front," said Ms Mawdsley.

"Obviously, people putting themselves in that situation are going to be exposed to the virus more and there are accounts of nurses succumbing to the flu after having volunteered for service."

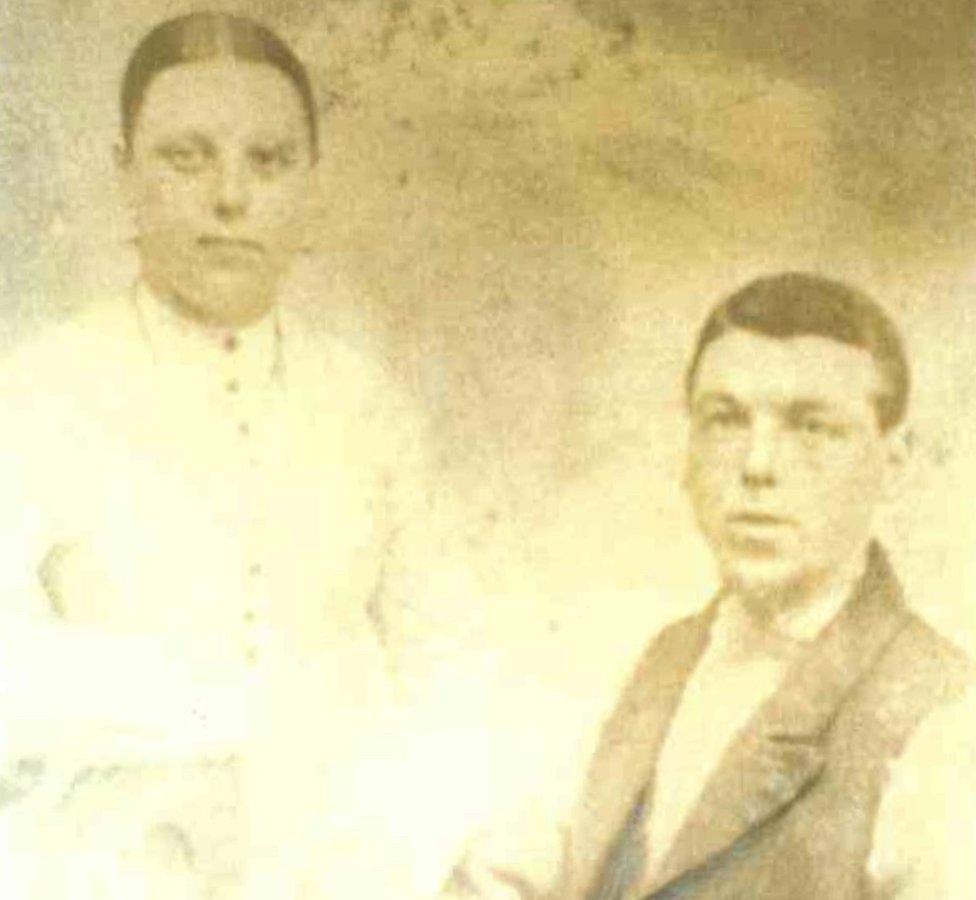

Elizabeth Ann Mawdsley's death certificate stated that she died from influenza and pneumonia

Today, those most vulnerable to flu are the very young and the elderly. But Spanish flu proved disproportionately fatal to those in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

"You've got this quite astonishing peak in exactly the age range of men serving in the war and nurses serving on the Western Front," said Ms Mawdsley.

A year into her research, the historian discovered her great-great-grandmother, 57-year-old Elizabeth Ann Mawdsley, died of flu on 14 December 1918.

"She was rather a formidable looking lady, quite stocky and determined looking," she said.

Ms Mawdsley's ancestor was the wife of a canal boatman in Lancashire and her death certificate stated she died of influenza and pneumonia.

An advertisement hailed Oxo as a preventative of influenza

"The average mortality rate of Spanish flu was between 2 and 5% worldwide," she said,

"That's a lot of people whose families would have lived through it, and survived to tell the tale.

"Many people will, like me, have undiscovered personal family links with this global catastrophe, perhaps to be found in diaries and letters."

Spanish flu has not generated the same commemorative culture as World War One and Two and consequently England has no specific memorials to the victims of the pandemic.

In the UK, the most deadly period of Spanish flu was between October and December 1918 and clusters of graves from that period can be found in cemeteries across the land.

"For me, these grave clusters serve as a kind of unofficial memorial to those that died, and illustrate the speed with which the disease struck and help us understand how terrifying it must have been," said Ms Mawdsley.

"These letters go further as one of the only other physical memory resource of the reality of what Spanish flu was like."

Additional reporting by Faye Hatcher

The Flu That Killed 50 Million is on BBC Two on Tuesday, September 25, at 21:00

A trailer for BBC Two documentary The Flu That Killed 50 Million

More on the data

The BBC England data unit analysed medical officers' reports for various English towns that had been digitised by the Wellcome Library in order to find out how many deaths were specifically attributed to influenza in 1918 and 1919.

Where possible we have also given the overall number of deaths recorded but the way in which individual officers recorded their statistics varied from area to area.

- Published19 September 2018

- Published21 May 2018