Pepe's story: How I survived Spanish flu

- Published

José Ameal, here with his mother

José Ameal remembers his aunt and uncle would keep the curtains by his bed drawn "so I wouldn't see the funeral processions".

But like any four year old, Mr Ameal - Pepe to his friends and family - was curious enough to peer outside on to the streets of Luarca, a fishing town on Spain's north coast.

"So many dead," recalls Mr Ameal, now aged 103, of what he saw that autumn of 1918, when he caught the virus known around the world as Spanish flu - a pandemic that is thought to have killed at least 50 million people.

Still living in his native Luarca, Mr Ameal is believed to be the oldest flu survivor in the country that gave its name to the virus, despite it likely originating elsewhere.

Not so Spanish after all

Recent research suggest the influenza may have started in the United States as early as 1916, and was brought over by US forces coming to fight in World War One the following year.

Wherever it started, the disease spread like wildfire amid unhygienic and confined conditions in trenches and training camps.

The virus spread around the world, but was thought to have originated in the US

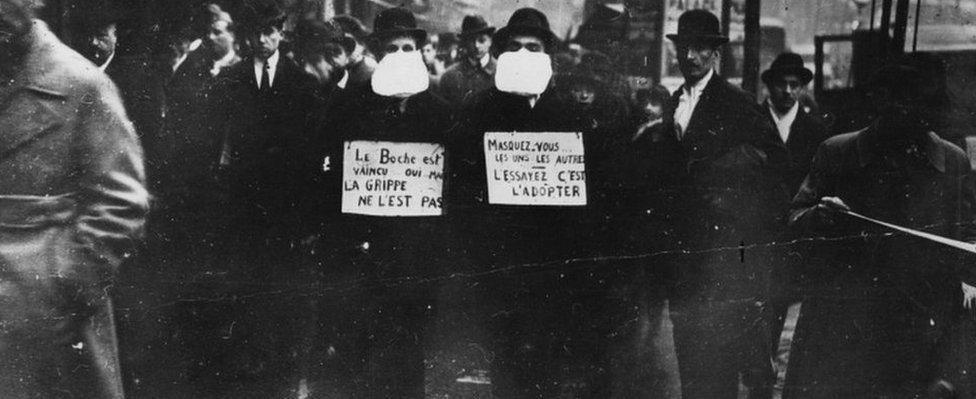

News of the pandemic was suppressed in belligerent countries to avoid demoralising the population and offering a propaganda coup to the enemy.

So it was in neutral Spain where the first reports of the rampant influenza emerged, probably giving rise to the name Spanish flu or "Spanish Lady".

"It is truly a strange thing to come across a relative, executor or friend who is not sick with the flu or convalescing from it," reads an article in a May 1918 edition of Spain's ABC daily newspaper.

This short piece about the spread of the virus ran as a chronicle on Madrid life between battle reports from the front

Mr Ameal remembers inhaling vapours from cooked seaweed and eucalyptus leaves. He says those who were saved in Luarca owed much to a doctor called Don Ceferino, who visited the sick without charge.

In Luarca, the funeral processions went up the hill to the church of Santiago at Ribadecima.

It was abandoned shortly afterwards, amid fears the large number of flu victims buried there could cause a fresh epidemic.

Around 500 people, a quarter of Luarca's population, died between 1918 and 1919.

The virus is thought to have spread to Spain through migrant workers in France

What 'Spanish flu' did to Spain

The disease had already ravaged France, the US and elsewhere before Spain, but the strain of the H1N1 virus that became internationally known as Spanish flu hit the local population hard.

In Spain, the disease was sometime referred to as the French flu as it was probably spread throughout the country by French migrant workers.

Starting in central and southern France, close to WWI battlefields and army camps, and following the railway path from the north as far west as Portugal and south to Andalucia, the influenza spread to nearly all of Spain's provinces.

King Alfonso XIII was among an estimated eight million Spaniards infected out of a total population of just under 21 million.

At least 260,000 died in Spain, with access to medical care and drugs extremely limited among the wider population.

All over Spain, the dead piled up as funeral parlours ran out of coffins and the Church ordered a special short version of the Mass service for the dead.

Church bells were prevented from tolling the dead to avoid alarming the population and the mayor of Barcelona requested the army's help for the transportation and burial of victims as city hall workers became scarce.

Pepe and all his seven younger siblings survived the pandemic.

"He comes from strong stock so he got through," says Marino Guardado, Mr Ameal's son-in-law.

"Pepe was the only child living with his uncle at that time, so perhaps that's why he was the only one who caught it."

Four of Mr Ameal's siblings are still alive, with Manolo set to become the second in the family to turn 100 in May.

Civil war prisoner

Surviving Spanish flu was not Mr Ameal's last brush with misfortune.

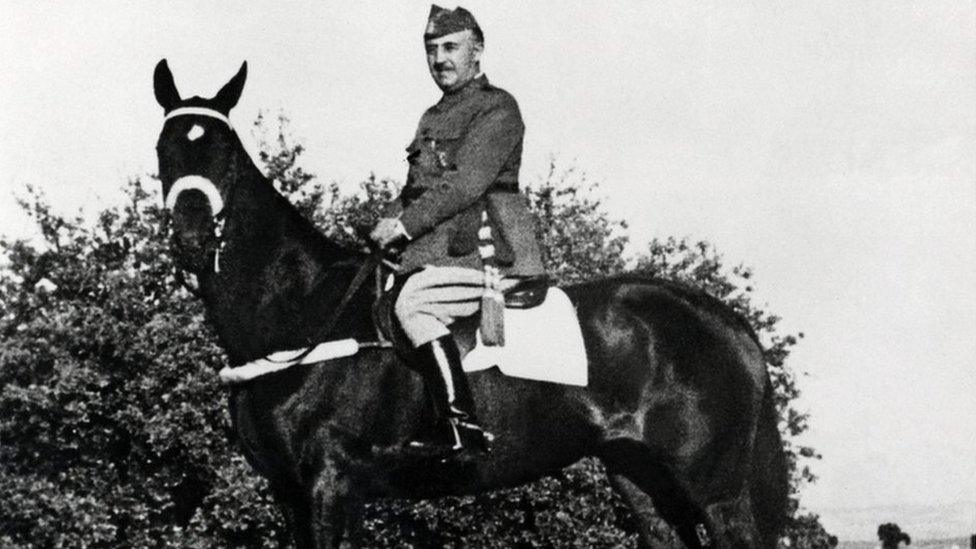

In 1939, at the end of Spain's three-year civil war, he was herded into a concentration camp outside Madrid by soldiers from Gen Francisco Franco's victorious Nationalists.

Gen Francisco Franco's Nationalists won the Spanish Civil War (1936-39)

According to Mr Guardado, Mr Ameal managed to escape by bribing a Moroccan soldier with a watch.

He proceeded to walk 20 miles to his Madrid home where his first wife, Isabel, was waiting for him.

"He doesn't talk about the war because he says he saw so much misery and suffering that he doesn't want to remember it," Mr Guardado says.

After the war, Mr Ameal lived in Madrid for another two decades, working as a taxi driver and chauffeur for bullfighters before moving back to Luarca and opening a bar.

Pepe had two sons with Isabel before she died in 1951. In 1955 Mr Ameal married again, to María Luisa, a woman 11 years his junior with whom he has two daughters.

"He remains in fine form. He goes down to the bar below his house in Luarca to see his friends every day," says Mr Guardado.

Mr Ameal says his plan is to live to 110. "Why go on longer?" he says.

For the bedbound boy who peeped at coffins drawn up the hill on carts, the last 100 years have been an adventure he could so easily have missed altogether.

- Published28 September 2017

- Published11 November 2016

- Published3 December 2016

- Published17 July 2016