Inside the school for bullied children

- Published

Lily Povey says Northleigh House School instilled her with the confidence to enjoy learning

Bullying blights the lives of many pupils, but what happens when children are left so sick with anxiety that they refuse to go to school? In the Midlands, a tiny specialist school has been helping youngsters rediscover their confidence and achieve their potential.

When you walk into the reception of Northleigh House School, Benji the school dog soon offers his paw, and there's the homely aroma of cakes being baked.

New pupils here soon learn that teachers are to be addressed by their first names and discover that teaching is either one to one or in small groups.

Pupils are encouraged to work at their own pace and new students start off gradually; in the early stages they are even allowed to sleep in an upstairs room if they choose.

School founder Viv Morgan, pictured here with Benji, set up Northleigh after reading about a teenager's suicide

Lily Povey had changed primary school four times as a result of bullying and had not been in mainstream education for two years when she began attending Northleigh in 2015.

One memory that endures from the days before Northleigh is of a girl spitting on her plate of food after being encouraged by another.

The 18-year-old can't ever recall being happy at school before she left mainstream education.

"I think it was the whole environment in general; I just didn't get along with it and I wasn't very social," she says.

"I didn't like to talk to other kids and I just kept to myself. With primary school, some girls were quite nasty from about eight.

"I had to be forced to go - I really hated it. I would cry and would make up any excuse not to go."

Some girls who bullied her went on to the same senior school and encouraged others to put her down.

"It got to the point that I couldn't go in any more; it would just make me feel sick."

Aaron, pictured aged 12 at Northleigh and now, said he had previously been "agitated and moody" but became much happier after changing schools

Aaron Kirsch's story is a similar one.

Growing up in a small Warwickshire village, he was anxious about the move to a large senior school shortly after his 11th birthday. Diagnosed with dyslexia, he also worried about the workload.

He was soon struggling with the change and his anxiety escalated after he was bullied on the bus home.

"It was name calling from a main group of people," he says. "It was physical a little bit as well - it wasn't massive, just pushing and shoving.

"I was already very anxious and that added to it."

Aaron could no longer face the bus journeys and his parents began driving him to school.

"I wouldn't even leave the house, so getting to school was always a struggle and some days I ran in front of the car as they were trying to pull away," he says.

Near the end of his first term, in December 2011, he panicked after being dropped off.

He remembers a teacher taking him to an office and locking the door, telling him to unlock it from the inside and go to class when he felt ready.

"I had a massive panic attack when he left me on my own," he said.

"I rang my dad and I told him what had happened and he picked me and I never went back again."

Mrs Morgan carried on at the school after her husband Fred died aged 96 in 2017, and was recently appointed MBE for services to education

Aaron's parents were able to get local authority funding so he could become one of the first pupils at Northleigh House.

The school had been set up months earlier by retired couple Viv and Fred Morgan in their former B&B in Hatton, near Warwick.

Mrs Morgan says the idea for the school stemmed from her picking up a newspaper left by a B&B guest and being shocked to read the story of Simone Grice, a vulnerable 15-year-old who left school through bullying and later took her own life.

She ultimately decided to set up a school where vulnerable children could benefit from a "therapeutic learning environment".

Seven years on and Northleigh House, which Mrs Morgan says gets a lot of support from the community and local firms, has taught about 70 youngsters.

For Aaron, going there was a huge turning point.

"I basically went straight to Northleigh and I loved it instantly," he says.

"There was a fire lit and it has always felt very homely. It always felt safe because of that.

"They won't make you do something if you are not ready and they focus on you as a person.

"And they realise that if you are doing well mentally, then you'll do well at school."

Lily found a love of photography at Northleigh and it became a way for her to express her feelings

Receptionist Nikki Perks explains how some new children are so anxious they "will not get out of the car". She finds one of the most rewarding things about working here is seeing pupils' confidence blossom.

The criteria for attending are simply "struggling and not going to school".

"We don't know if they have been bullied because they don't tell you," says Mrs Morgan.

The emphasis is on kindness and respect - "happiness first and learning after". Pastoral sessions are emphasised and children are encouraged to speak about their problems.

Mrs Morgan says she has taken away some of the "structure" of mainstream education, in that her pupils work at their own pace, concentrate on subjects that most interest them and are "not shouted at".

However, she insists this style of learning is "not a soft option". There are clocks in all rooms and pupils have to get to lessons on time.

"We adjust to what they can do, and they do very well," she says.

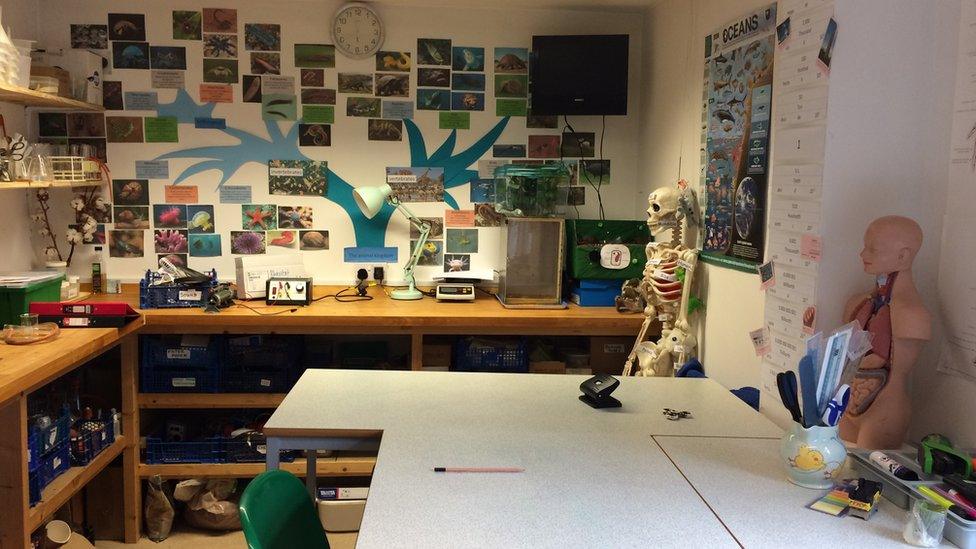

Aaron said science lessons were "fun" and inspired his interest in the subject

Woodwork and photography are among popular activities, as well as learning about nature from the school's wildlife pond.

Ofsted inspectors rated the school satisfactory in 2012 and said areas such as pupils' progress and quality of education could be improved. But they liked its overall philosophy and said it was helping bullied children recover.

Staff set about fulfilling inspectors' requirements and now Northleigh offers the full GSCE curriculum and some A-levels to its 30 children aged 11 to 17.

It employs 25 teachers, including four who work full time. The school was rated good in 2016 in its last Ofsted report, external, which praised its "excellent pastoral care" and found staff were very skilled at helping children have more confidence in themselves and their abilities.

"Pupils who were fearful and used to hide away are now starting to enjoy meeting others and learning from new experiences," inspectors said.

Thirty pupils are currently at Northleigh House School, which teaches children from Warwickshire and the West Midlands

A Centre for Social Justice report said it was estimated about 16,000 children between the ages of 11 and 15 were absent from state schools in England with bullying as the main reason, external.

The Department for Education said schools should respond sensitively and do "all they can to ensure that all children can attend school in a calm and safe environment". In extreme cases, when a child cannot be reintegrated into school, it could mean a transfer to another mainstream school or "alternative provision".

Lauren Seager-Smith, chief executive of charity Kidscape, says how each school deals with this is a "lottery" and they need more support.

Educational provision across England for children who self-exclude because of bullying is "patchy" and dependent on where they live, she says.

Lily took this photograph in the garden at Northleigh House

Lily certainly feels as though Northleigh has enabled her to have the education she was unable to receive before.

At first, she felt scared at Northleigh and ate lunch alone, but gradually grew in confidence.

She says she had "very low self-esteem" but was helped by pastoral sessions with a caring mentor.

"I always remember my mentor continually reassuring me to believe in myself and telling me that I could do whatever I wanted to do, no matter what anyone else said," she says.

"That has stuck with me since and always will - because she was right."

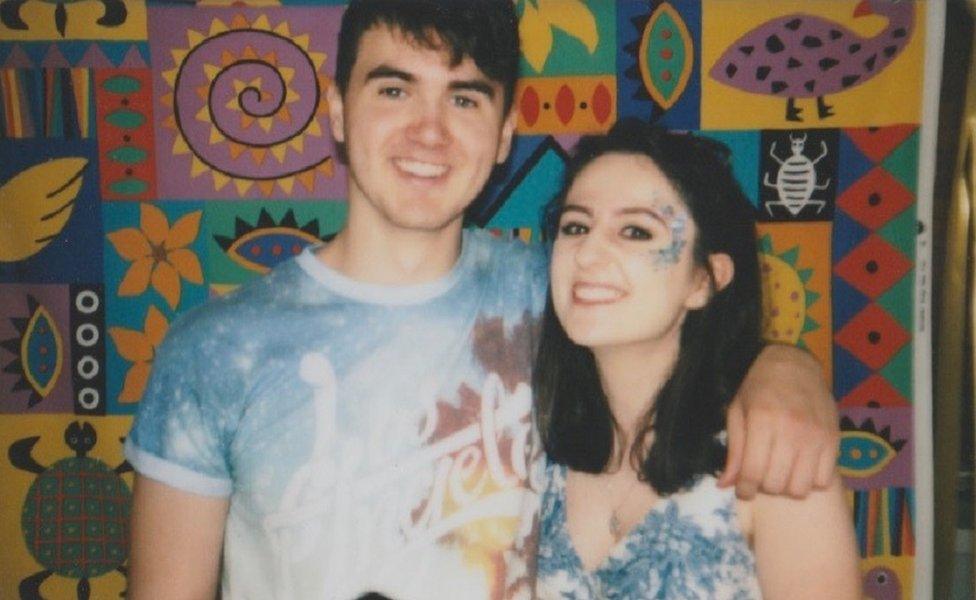

Lily and Aaron found the confidence to go on to college

Lily and Aaron have now left Northleigh, where not only did they find a love of learning, they also found each other. The teenagers have been in a relationship for 18 months.

She began a hairdressing course at college last year, with Aaron waiting in the library on her first day to support her.

Lily is enjoying college, where she is moving to a health and social care course, and is feeling positive about the future.

"Before, I wouldn't speak to anybody really. I found it very difficult," she says.

"I couldn't get my words out and was still very anxious when I went to college, but felt I could do it."

Aaron has discovered a love of science, a subject he previously "hated".

He started college in 2016 to study psychology and biology A-levels and is looking forward to starting a third A-level in his favourite subject, chemistry, in September. He hopes to go on to university to study medicine.

"There was no chance I was going back to secondary school, so without Northleigh I wouldn't have even got my GCSEs," he says.

"I don't know where I would be without Northleigh, to be honest."

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and sign up for local news updates direct to your phone, external.

- Published6 November 2023

- Published9 November 2018

- Published5 June 2018

- Published7 December 2017