Sonic, Street Fighter and the 'golden age' of gaming magazines

- Published

Retro gaming is enjoying a surge in popularity with Nintendo, Sega and Sony all releasing mini versions of classic 1990s machines. The decade also spawned a boom for console magazines desperate to win the publishing war for pocket-money pounds.

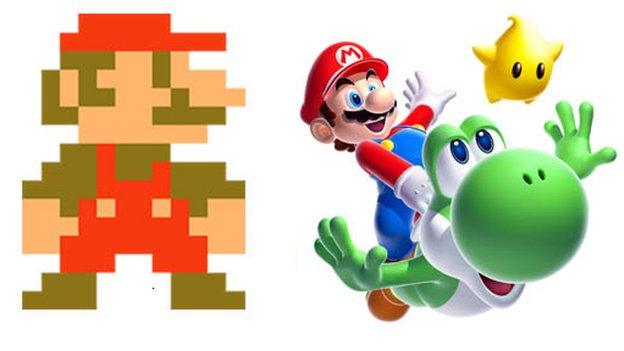

Sonic, Street Fighter II and Super Mario World. Between them, they would define a generation of gaming.

As standard-bearers for Sega and Nintendo's competing machines, the titles provided thrilling leaps into colourful new worlds and cemented home gaming as a multimillion-pound industry.

With the Mega Drive and Super Nintendo becoming must-haves for children up and down the land, it is an era still fondly recalled by many. Indeed, Sega will be the latest firm to cash in on nostalgia for the period with the imminent release of the Mega Drive Mini following compact versions of Nintendo's NES and SNES, and Sony's PlayStation.

Vying for players' attention first time around would be a proliferation of equally enchanting magazines - all keen to satisfy the voracious appetite for news and reviews and, crucially, secure a lucrative foothold in the quickly expanding market.

For the small teams of journalists working late into the night to meet punishing publishing deadlines, it would be a "golden age" as wondrous as a high-speed spin though Sonic's Green Hill Zone or dodging dinosaurs in Mario's Donut Plains.

Mean Machines lauded Street Fighter II as "one of the greatest video games in the world" upon its 1992 Super Nintendo release

"We absolutely loved video games," recalls Julian "Jaz" Rignall, editor of Mean Machines - an irreverent magazine from London-based Emap that stole a march on the opposition and quickly became a big seller.

"The technology was facilitating new and exciting games, and every month we seemed to have something incredible turn up. I remember when the Super Nintendo was delivered for the first time, taking it out of the box and playing Super Mario World. The whole office would stop, we'd go into the games room and crowd round the screen. There was a high level of excitement and that came across in the magazine."

Beginning life as a section within Computer & Video Games (CVG) in 1987, it had focused on emerging platforms such as the PC Engine, Game Boy and Atari Lynx.

The first magazine under the Mean Machines banner would hit the shelves dated October 1990 and coincide with the UK release of the Mega Drive - two years after its Japanese debut.

"The office was a mess," laughs Rignall. "There were games and bits of hardware and old computers everywhere. We would occasionally have tidy-ups, although for the most part it was an absolute dump.

"But, you know, it was the perfect environment for us and that allowed us to produce a really great magazine."

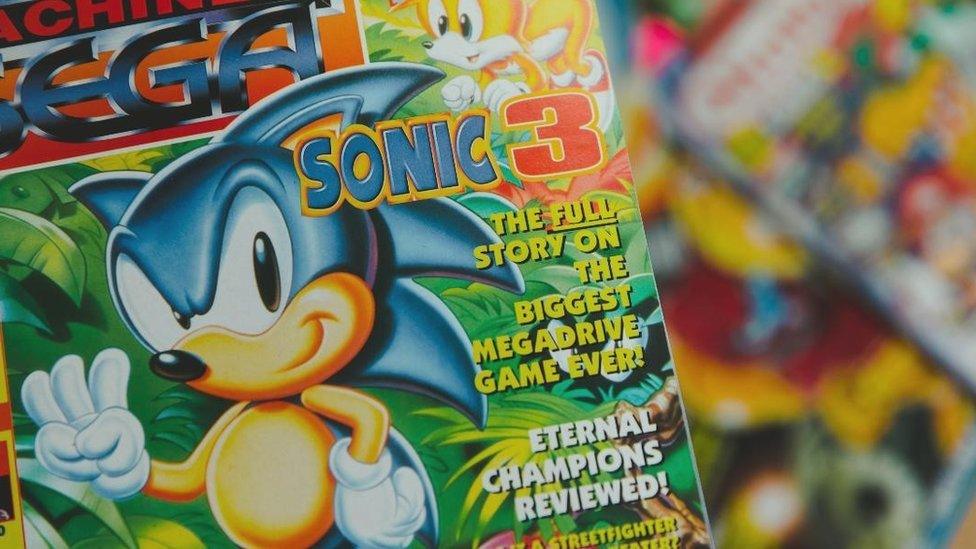

Sega's answer to Nintendo mascot Mario, Sonic the Hedgehog quickly became one of the most recognisable characters in gaming

With an initial print run in the region of 30,000 copies, monthly sales would soon go on to top 150,000. So what made Mean Machines such a huge success? Humour and personality were undoubtedly key ingredients.

While striking features acclaimed the merits of Street Fighter II, readers were mercilessly mocked by Rignall's "Mean Yob" letters page persona and Insult Corner saw near-the-knuckle put-downs hurled around with glee.

"It was very much part of the remit not to talk down to the readers," he says. "We really wanted to be inclusive. It had a very juvenile and anarchic humour - double entendres, being rude but not quite being rude. We wouldn't swear, but we would allude to swearing. The personalities of the staff really came through, and the tone and style was very different to most other magazines out there.

"Most important of all, we were very, very enthusiastic about video games."

As the likes of Streets of Rage, Super Mario Kart and Star Fox drove sales of Sega and Nintendo's machines in a battle that came to be dubbed "the console war", advances in desktop publishing meant magazines could be put together more quickly and cheaply than ever before.

You may also be interested in:

Nintendo's watchful eye meant Jaz Rignall's team had to be "a lot more careful" about what they wrote after securing the official magazine licence

Circulation revenues were boosted by booming advertising profits as games companies, big-name retailers and small independent shops snapped up space. It was low risk, high reward for Emap and rivals such as Bath-based Future.

GamesMaster, Mega, Total! and Edge would all be launched between 1991 and 1993, while Rignall's title would split to become Mean Machines Sega and Nintendo Magazine System to capitalise on winning the official Nintendo console publication licence. Easily the most eye-catching, though, would be Future's Super Play.

Its intricate Japanese-style art and focus on anime (the term for Japanese animation) immediately set it apart when its debut issue launched with a cover date of November 1992. Columns explored the idiosyncrasies of Far East cartoons and comics, while dazzling images adorned each cover courtesy of illustrator Wil Overton.

"The technology was just good enough where a small team of four or five people could make quite a nice magazine and there was an audience of many, many tens of thousands that would lap it up," says its first editor, Matt Bielby. "There were all these competing games platforms and any market where there's competition tends to be quite vibrant because people choose one side or the other.

"It's like Blur v Oasis, or whatever it might be. If there's a little fight going on - even if it's not serious - it makes things more exciting."

Wil Overton's Super Play covers "would punch you with bright colours," recalls editor Matt Bielby

Having also been offered the editor's chair at Sega-focused Mega, he chose Super Play as a means of indulging his "obsession" with Japan.

"The whole look and feel was massively important. I went to Japan at one point and picked up lots of magazines, and we went to places like the Japan Centre in London and would buy imported magazines on any subject - cars, fashion, anything. Because the team were big fans of the subject matter, elements of our lives blended into each other.

"We didn't have a life outside of Super Play very much, but that was fine. We quite liked it like that. Two of them married each other so that kind of worked."

By late 1993, it would be selling 50,000 copies a month. But how conscious were the writers of the influence they wielded?

"You were very aware these games were not cheap," Bielby admits. "Often it would be 50 quid or something of that order, which was a hell of a lot when you consider how much a pint of milk or beer was back then. If anyone bought a game they were investing quite a lot of money into it and they deserved something that would last them and they'd really enjoy.

"In retrospect, it was clearly a very special period of time where you had lots of very young, inexperienced people let loose with magazines that got big audiences. We were in a little golden age through the 90s."

Street Fighter II Turbo created much initial excitement, although Super Play later reported warehouses had many unsold copies

As the Sega Saturn, Nintendo 64 and Sony PlayStation usurped their predecessors, another wave of titles inevitably hit the shelves.

Steve Jarratt, launch editor of Future's Edge, Total! and Official UK PlayStation Magazine, describes it as a "licence to print money" for the publishing companies.

"We felt invincible. I rode the glory days. We'd make about £1 profit on a £2.99 magazine, printing 13 times a year. The PlayStation magazine's sales peaked at about 350,000 and that's at five or six pounds for each copy with a demo disc on the cover. It was generating a huge amount of wealth. Future made an enormous amount of money."

Change would come though.

In a painful irony mirroring the finite lifespan of the machines they covered, games magazines would be rendered outdated by technology's relentless march. As the new millennium rolled around, it was "game over" for print.

Japanese role-playing games, such as Secret of Mana, were covered heavily by the magazine

Free to read and unconstrained by monthly deadlines, websites allowed the instant publication of information while games could be viewed more easily than via the VHS cassettes magazines had offered as promotional gifts. Circulations plummeted.

"On a bad month [in the 1990s] we might lose 20,000 sales. Now most people would think 20,000 sales [in total] would be brilliant," Jarratt says. "We knew the internet was coming, but didn't appreciate the full impact. I don't think anyone did.

"At first it was slow to load and visuals were clunky so it didn't feel like much of a threat. Then came a dawning all the stuff we were doing could appear online and over time we started to see people covering video games."

No longer as profitable, publishers closed title after title. While a small number remain today, circulation figures are dwarfed by those that went before.

Helen McCarthy, founder of Anime UK magazine, enlightened Super Play readers on the joys of Japanese animation

"Instead of investing in the product, at Future it always felt like lots of cost-cutting to keep the [profit] margins up," says Jarratt, who left the company in 2011 and now works on a freelance basis contributing to the likes of Bitmap Books' series on retro gaming.

"You end up under so much pressure. No matter what you do sales go down, revenue falls off. You put your fingers in the holes in the boat to keep the water out. The internet is a double-edged sword. It's amazing for communication, but at the same time it's absolutely slaughtered certain markets. The High Street is dying, newspapers and magazines are struggling."

So has anything been lost with the disappearance of the printed page or are gamers simply better off?

"There was something about the physicality of magazines," says Rignall, who has worked in the games industry in the United States since 1994. "But ultimately things have evolved.

"These days you can read about whatever you want and you're not limited by having to wait for a magazine to turn up. I think it's cool."

Photography by Caroline Briggs

- Published1 May 2019

- Published28 June 2017

- Published13 May 2014

- Published4 June 2012

- Published23 June 2011