The British Victorians who became Muslims

- Published

Lady Evelyn on a trip to Luxor in Egypt

At the height of the Empire, a select band of British people renounced Christianity and converted to Islam. These are the stories of three such pioneers, who defied Victorian norms at a time when Christianity was the bedrock of British identity.

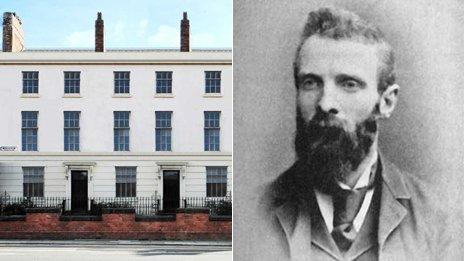

Abdullah Quilliam

William Henry Quilliam adopted the name Abdullah after his conversion

Solicitor William Henry Quilliam became interested in Islam after seeing Moroccans pray on a ferry during a Mediterranean break in 1887.

"They were not at all troubled by the force of the strong wind or by the swaying of the ship. I was deeply touched by the look on their faces and their expressions, which displayed complete trust and sincerity," he recalled., external

After inquiring about the religion during a stay in Tangiers, 31-year-old Quilliam became a Muslim, describing his new faith as "reasonable and logical and, personally, I felt it did not contradict my beliefs".

While Islam doesn't oblige converts to change their names, he adopted the name of Abdullah.

On his return to England in 1887, he became a preacher, and was said to be instrumental in the conversion of about 600 people across the UK.

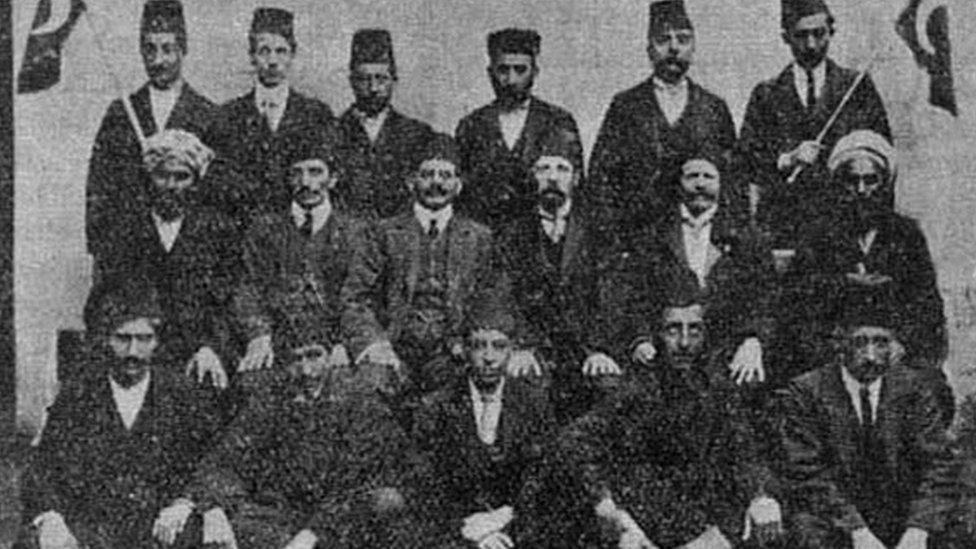

Quilliam is credited with converting 200 locals and 600 people across the UK

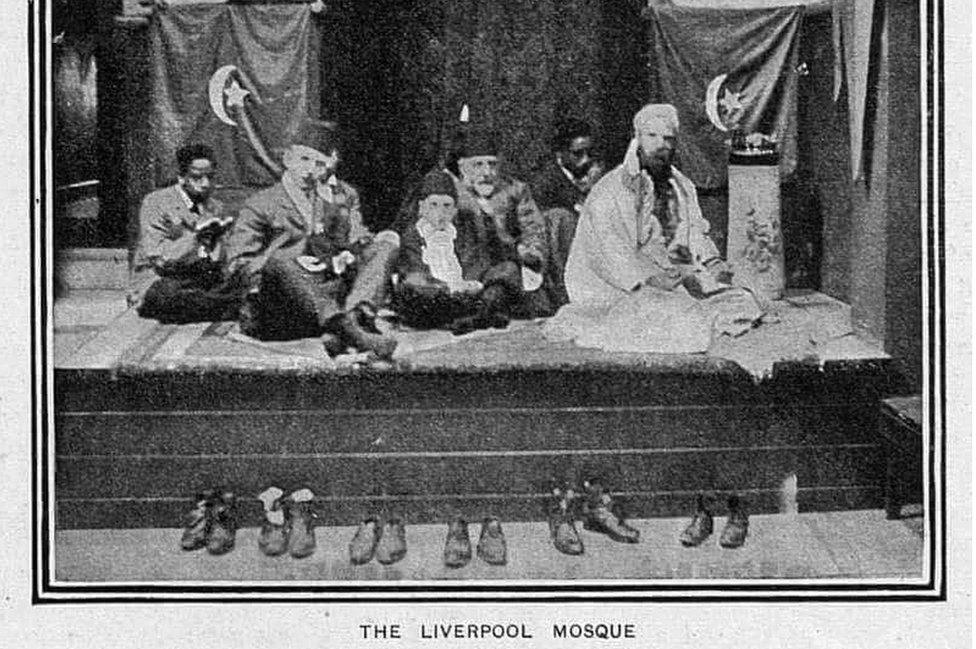

He also established the country's first mosque, external that year in Liverpool - regarded by many at the time as the "second city of the British Empire".

Queen Victoria, who ruled over more Muslims than the Turkish Ottoman Empire, was among those who ordered his pamphlet "Faith of Islam", which summarised the religion and was translated into 13 languages., external

She is said to have ordered six more copies for her family. But her willingness to learn was not always matched by a wider society which believed Islam to be a violent religion.

In 1894, the Ottoman sultan - with the approval of the Queen - appointed Quilliam as Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles, a title reflecting his leadership in the Muslim community.

An illustration of Queen Victoria investing Ottoman Sultan Abdul Aziz (centre) with the Order of the Garter

Despite the official recognition, many Liverpudlian converts faced resentment and abuse over their faith, including being assaulted with bricks, offal and horse manure.

Quilliam believed the attackers had been "brainwashed and led to believe that we were bad people".

He was known locally for his work with the underprivileged - advocating trade unionism and divorce law reform - but his legal career came to ruin when he tried to help a female client seeking a divorce.

A honey-trap was set up for her allegedly adulterous husband - a practice not uncommon at the time - but the attempt failed and Quilliam was struck off.

Worshippers still pray at the Abdullah Quilliam mosque in Liverpool, which was opened in 1887

He left Liverpool in 1908 to minimise the scandal's impact on the Muslim community. He resurfaced in the south as Henri de Leon, although many knew who he was, according to Prof Ron Geaves, who has written a book about Quilliam.

Although his profile diminished, he became involved with the country's second oldest mosque, built in Woking in 1889, and was buried in the Surrey town after his death in 1932.

The Liverpool mosque bears his name to this day.

Quilliam also became involved with Britain's second oldest mosque in Woking

Lady Evelyn Cobbold

Lady Evelyn, pictured with her husband John Cobbold, felt she was "Muslim at heart"

It wasn't uncommon for members of the upper classes to be fascinated by Islam, often inspired by travels in Muslim lands.

From an aristocratic family, Edinburgh-born Lady Evelyn Murray spent much of her childhood switching between life in Scotland and north Africa.

"There, I learnt to speak Arabic and my delight was to escape my governess and visit the mosques with my Algerian friends, and unconsciously I was a little Muslim at heart," she wrote.

At her ancestral estate of Dunmore Park, she excelled at deer-stalking and salmon-fishing.

Her explorer father, the 7th Earl of Dunmore, was often away in destinations including China and Canada. Her mother, later a lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria, was also a keen traveller.

Lady Evelyn inherited her parents' wanderlust and it was in Cairo where she met and married her husband John Cobbold - a businessman who was part of the brewery dynasty that ran Ipswich Town FC.

Lady Evelyn was the first British woman known to have performed the Hajj

It is not known when she converted to Islam. The seed may have been sown by her childhood travels, but Lady Evelyn's faith was apparently cemented after a holiday in Rome, where she met the Pope.

"When His Holiness suddenly addressed me, asking if I was a Catholic, I was taken aback for a moment and then replied that I was a Muslim," she later wrote.

"What possessed me I don't pretend to know, as I had not given a thought to Islam for many years. A match was lit and I then and there determined to read up and study the faith."

It was the religion's spiritual aspect that attracted many converts, according to historian William Facey, who wrote the foreword to Lady Evelyn's memoirs.

He says they followed a "belief that all the great religions shared a transcendent unity… behind the superficial doctrinal detail that divides them".

In the Middle East, Lady Evelyn - referred to as "Lady Zainab" by her Arab friends - often had access to areas reserved for women and wrote about the "dominating influence of women" in Muslim culture.

At the age of 65, she embarked on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca - the first British woman on record to complete the feat.

It offered her "endless interest, wonder and beauty" and her account was later published in a book, Pilgrimage to Mecca.

Lady Evelyn later wrote about her pilgrimage

Little is known about her life afterwards other than she travelled for a short period in Kenya. She died in an Inverness nursing home in 1963 at the age of 95, having instructed that a bagpiper play at her funeral and a Koranic passage, known as the "verse of light", be inscribed on her gravestone.

The marker, located in her Glencarron estate in the Highlands, was later slashed with a knife - perhaps testament to the strong views her conversion drew.

"I am often asked when and why I became a Muslim," she wrote in her memoirs.

"I can only reply that I do not know the precise moment when the truth of Islam dawned upon me.

"It seems that I have always been a Muslim."

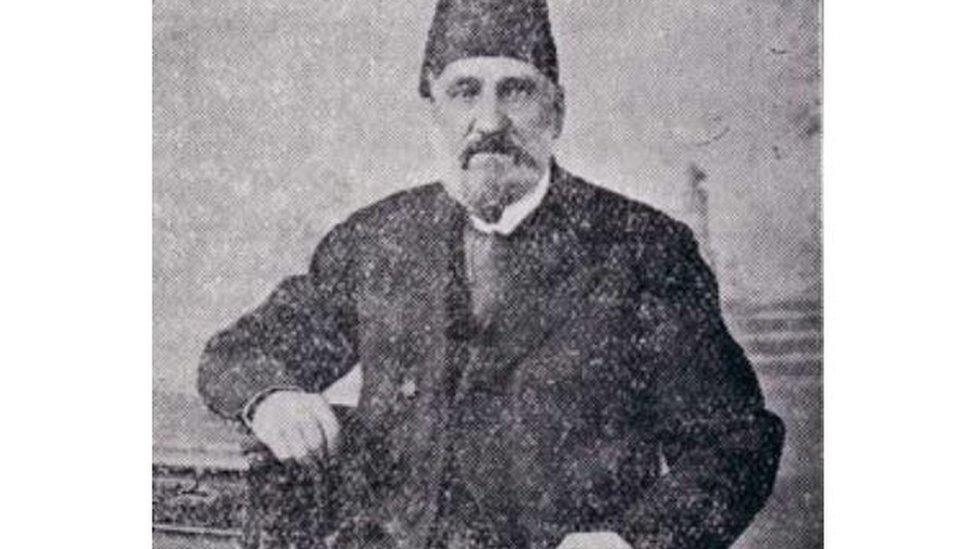

Robert Stanley

Robert Stanley converted to Islam at the age of 70

The narrative of Victorian Muslim history is usually dominated by those from society's upper echelons, whose accounts have been better preserved.

Keeping written documents, such as diaries, was "generally more a sign of being middle class", says Christina Longden, who only found out her ancestor became Muslim after her father researched their family tree.

Robert Stanley rose from working-class grocer to Conservative mayor of Stalybridge - a mill town near Manchester - in the 1870s.

According to Ms Longden, who has written a book and play about him, he was also a magistrate who set up a fund for workers sacked for not voting in line with their bosses' views.

She also found he regularly wrote about British colonialism to the newsletter of Quilliam's Liverpool mosque.

Robert Stanley (centre) with Abdullah Quilliam (right) at the Liverpool mosque

Stanley met Quilliam in the late 1890s after he had retired from his political career, and they became close friends.

"Robert was 28 years older than Quilliam so I think there may have been a bit of a father-son relationship there," says Ms Longden.

You might also be interested in:

It wasn't until he was 70 years old however, in 1898, that Stanley became a Muslim and adopted the name Reschid.

Ms Longden believes from her research that there were "no other Muslims" in Stalybridge at the time. Stanley later moved to Manchester and died in 1911.

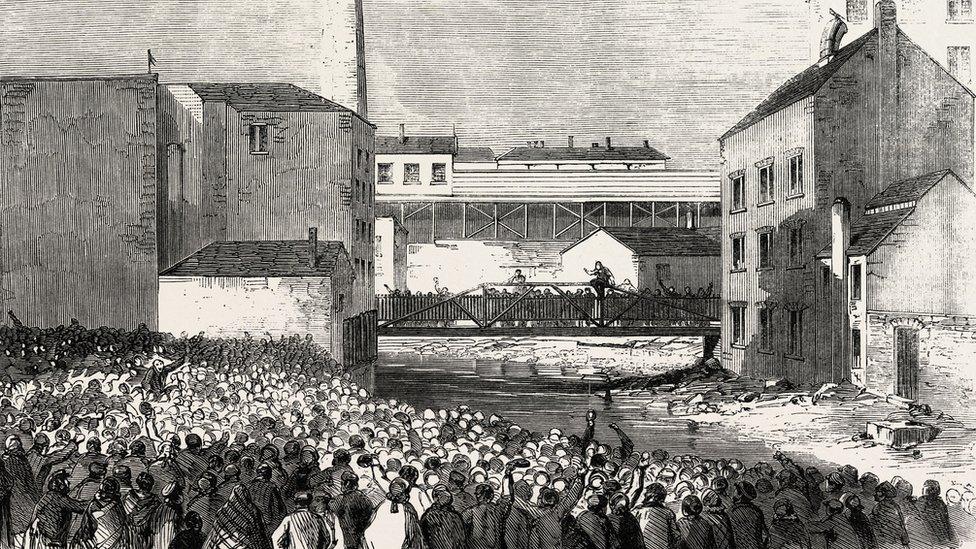

A 19th Century image shows workers on strike in Stalybridge

His conversion was kept quiet by his immediate descendants and was only discovered by the Longdens in 1998.

"Quilliam's granddaughter said this was 'an age when, if you didn't conform, your picture was turned to the wall for all time'," says Ms Longden.

Coincidentally, Ms Longden's brother, Steven, became a Muslim in 1991 after studying in Egypt as part of his university degree - seven years before finding out about Stanley.

When he heard about his ancestor's conversion, he recalls finding it "incredibly shocking, in a good way".

"The fact there was a man who chose to be Muslim at a time when you couldn't possibly imagine someone would do something so unorthodox... when you sit and think about it, well yeah, it's Manchester.

"People aren't afraid to stand up and say what they believe in, whether that's politically or religiously."

- Published12 November 2015

- Published27 June 2014