How smart are Highways England's smart motorways?

- Published

Smart motorways are being built across the country

Hundreds of millions of pounds are being spent to make large stretches of the UK's busiest motorways "smart" - but how do they work?

With about 400 miles of road already converted, and plenty more in the pipeline, many drivers will soon have used one.

What makes them "smart" are the computers constantly monitoring the road, which can change the speed limit on their own.

But this technology does not always run smoothly.

Drivers southbound on the M1 were stuck for up to an hour for no reason because of a "glitch"

On 20 June, a stretch of smart motorway between Leicester and Nottingham was supposed to reopen at 05:00 BST following roadworks.

However, a "glitch" left three lanes of the M1 closed for no reason, causing several miles of traffic tailbacks because the computer would not reopen the roads when told to.

Highways England described this as an "extremely rare" event. But just how much control do computers have over the new roads, and how do they know what to do?

How do smart motorways work?

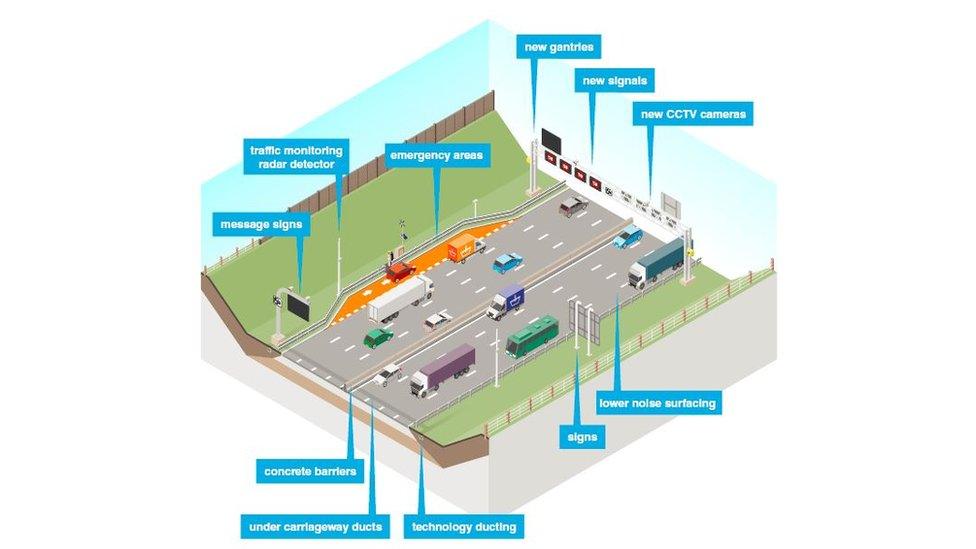

There are two main types of sensors computers use to keep an eye on the traffic, Matt Pates, who is in charge of the East Midlands for the authority, explained.

One is a set of copper loops buried in the road surface every few hundred metres.

When something metal, such as a car, passes over, it creates an electric current. This means a computer can tell how often and how quickly vehicles are passing over a certain spot.

It also knows the length and therefore roughly what kind of vehicles are passing by. It is the same technology used at some traffic lights to tell when there is a vehicle waiting.

Matt Pates said everyone was "shocked" by a smart motorway glitch on the M1

The other is a "side-fire radar", which does the same thing but with a beam projected from the side of the road.

These are now preferred because they are easier to maintain and the area around a copper loop is susceptible to potholes.

On top of this, Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras watch how long it takes for a vehicle to drive from one point to another. Highways England said it used technology to make the number plates it was tracking unreadable to others.

What can and can't a computer do?

All this data is constantly fed back to large banks of computers that decide if they need to intervene because the road is getting too busy.

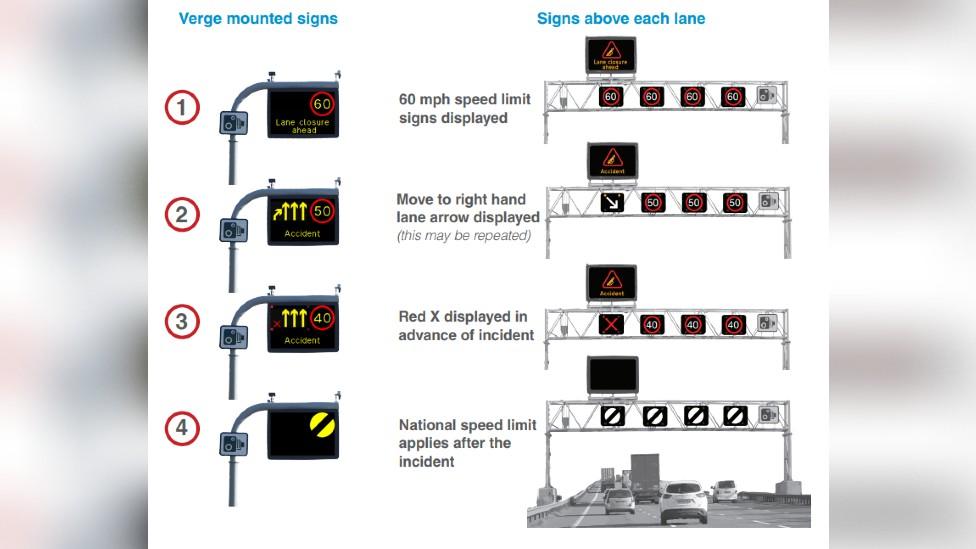

The software can lower the speed limit to 60, 50 or 40mph, and this is displayed on overhead gantries. Ignore these and motorists could face a fine, external.

The idea is to slow drivers down as they head to a busy area so traffic does not bunch up and create more congestion.

This decision will not necessarily be checked by an officer back in the control room, unless it is out of the ordinary.

Red X signs on a smart motorway - what you'll see

Mr Pates said people complained about having to drive slowly when there was no obvious congestion.

But he added: "[The computer] slows the traffic down before it breaks down, it doesn't wait for it to happen."

What a computer cannot do is react to something like a crash and it is not allowed to close lanes.

This is still done by a human in a regional control room who relies on CCTV, police patrols, Highways England officers and reports from the public.

More than 40 traffic officers monitor the East Midlands' motorways 24/7 from the Nottingham headquarters

Where are smart motorways?

Highways England said it had converted about 416 miles of motorway to one of the three types.

These are:

Controlled - people cannot drive in the hard shoulder

Dynamic hard shoulder - the hard shoulder can be opened

All lanes running (ALR) - the hard shoulder has permanently become a lane

All the planned new smart motorways will be ALR

England currently has more than 100 miles (161km) of ALR smart motorways.

Those already built are:

M1: J16 to 19, J23a to 25, J28 to 31, J32 to 35a, J39 to 42

M3: J2 to 4a

M4 J19 to 20

M5: J4a to 6, J15 to17

M6: J10a to 13, J16 to 19

M25: J5 to 7, J23 to 27

M62: J25 to 26

Are they better?

Recovery drivers have spoken about the dangers of having no hard shoulder

Mr Pates said the advantage of the smart motorway was more cars could drive on it, clearer instructions could be given to drivers and emergency incidents were more quickly reacted to.

But the disappearance of the hard shoulder worries some.

Jack Cousens, head of roads policy at the AA, said the organisation was concerned the emergency refuge areas that have replaced the hard shoulder - with one a little more than every mile on average - were not close enough together, and drivers might panic if they broke down and could not see anywhere safe.

Emergency bays have been built to replace the hard shoulder

In March, 83-year-old Derek Jacobs died after stopping his van on the M1 in Derbyshire in what was previously the hard shoulder, "possibly due to a mechanical problem", police said, external.

What exactly happened is still under investigation.

About six months earlier another woman was killed after a breakdown on the same stretch, external, the Derbyshire Times reported.

Samantha Cockerill, whose partner Steve Godbold was killed working in the hard shoulder, says ALR motorways are "crazy"

"It's expansion on the cheap," Mr Cousens said. "We get the need to deal with congestion but safety can't be the compromising factor.

"We want [Highways England] and the Department for Transport to go back to the drawing board and make sure this is the best thing we could be doing."

Mr Pates, addressing concerns about the hard shoulder, said it had been built decades ago when cars were less reliable and most drivers would now get advance warning before something went wrong with their vehicle.

He said a hard shoulder was not a "hospitable" place to be and smart motorways were "as safe, if not safer" without them.

MPs and police have raised concerns over people's safety on smart motorways.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published15 December 2018

- Published10 January 2017