Sterns nightclub: The raves in the house on the hill

- Published

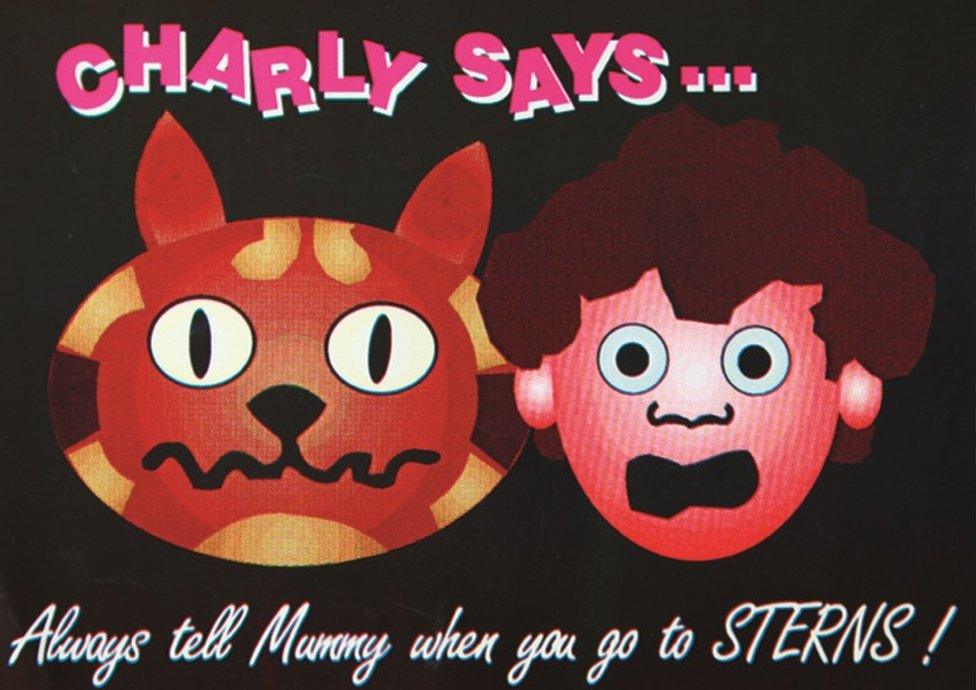

Flyers for Sterns often referenced well-known household brands

At the height of its popularity, ravers blocked the roads of rural Sussex trying to get to a 19th Century mansion whose floors pounded with the sounds of the so-called Second Summer of Love. But the success of Sterns nightclub would partially lead to its downfall. Just three years after it began, the party was over.

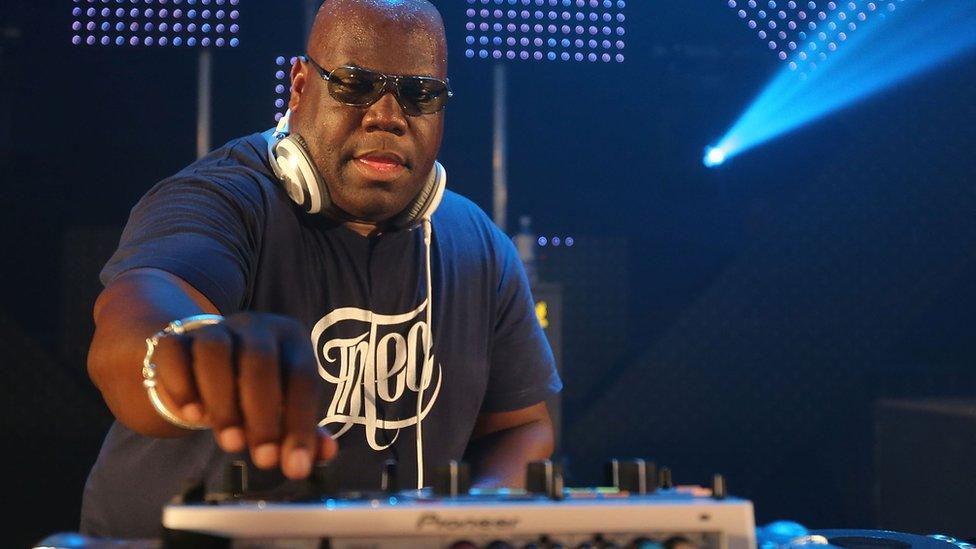

Worthing in the early 1990s was "a very boring place", remembers DJ Carl Cox - except for the fact the coastal town had a club that was "100% equivalent to the Hacienda" - the Manchester club that epitomised the rise of rave culture at the time.

"There was this lunatic club off the A24 - one of the most unlikely places in the world," says the house music legend and Space Ibiza pioneer, external. "It was in the middle of nowhere. There was no Uber, no cabs, no internet, and the line-up was 'London'.

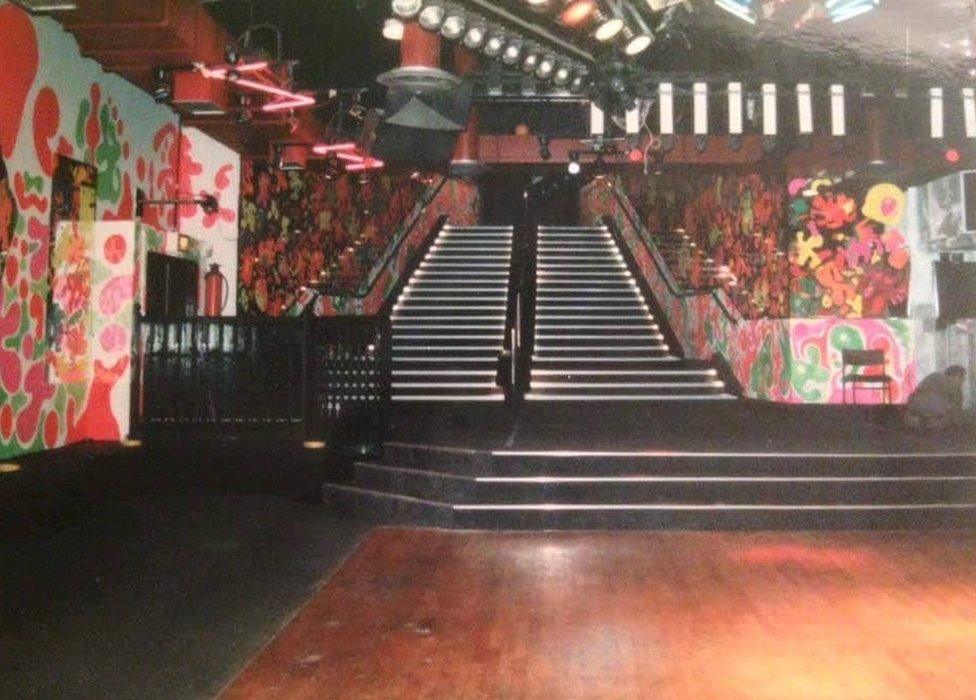

"You saw this manor house - it was the only place which had three floors when all other nightclubs had one. You went in and everyone was going mad. You went downstairs and they were going mad. You went underground and it was just going off."

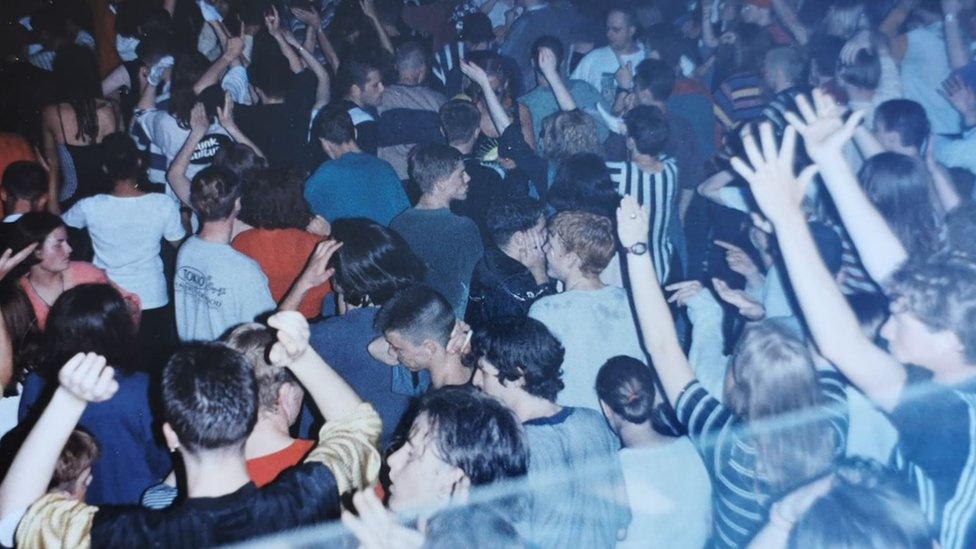

Parties at Sterns often went on into the early hours

The house formerly known as Sterns was bought in 1919 by Sir Frederick Stern - banker, horticulturalist and one-time private secretary to ex-Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

By the 1980s it was owned by Richard Garrett, who worked with music promoters Interdance. It was the vision of its leader Mensa that turned the mansion on Highdown Rise into a rave venue that predated super-clubs like Ministry of Sound, Gatecrasher and Cream and attracted headliners such as Moby, The Prodigy, Sasha, Fabio and Grooverider.

The club had a view of the sea from its top windows and overlooked a town that was - and still is - characterised by its older demographic. It was an unexpected location in which to find all-night raves which paid homage to the Second Summer of Love - a movement embraced by British youth culture between 1988 and 1989 that came from the house clubs of Chicago.

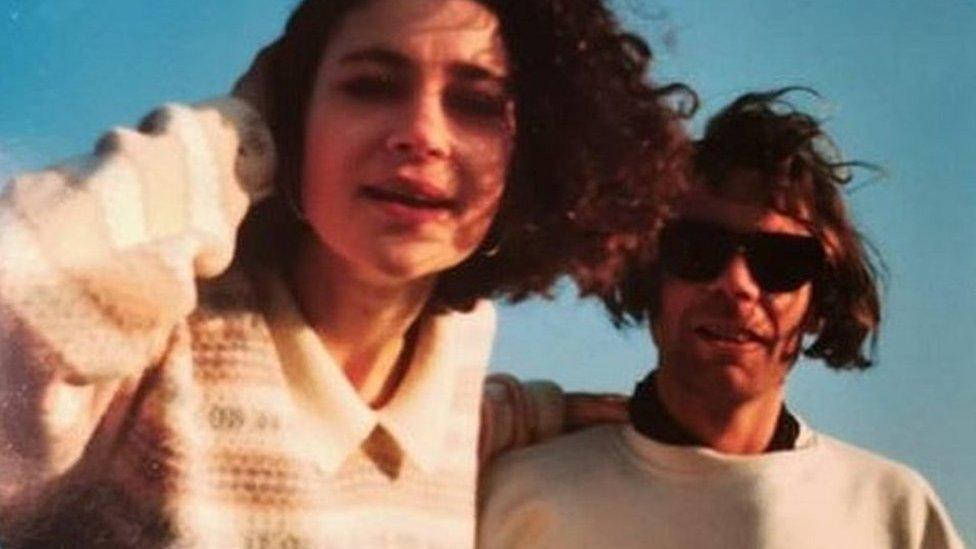

Rachel Jones and Mensa would regularly travel to London to hear the latest music

Life in Britain in the early 1990s was punctuated by Freedom to Party marches and Conservative rule, while the headlines were dominated by ecstasy and illegal raves. The prevalence of the latter, particularly those in warehouses and fields around the M25, eventually led to the Criminal Justice Act, which famously targeted music "characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats, external".

But parties at Sterns, which operated from 1990 to 1993, were legal under a public entertainment licence granted by Worthing Borough Council. The official cut-off time was 03:00 but the music often carried on until 06:00, under what former club staff describe as a "gentleman's agreement".

While it was licensed as a members-only club, its exclusivity was seemingly elastic. Mensa's girlfriend, Rachel Jones, kept a handwritten list of members which she recalls topped about 12,000 names.

"I was 19 and it was phenomenal. We travelled, we did events in other cities, we lived the good life.

"It was a vibe - that's what Mensa put into the place. I can see him now, standing out there, wearing a suit, the pride on his face."

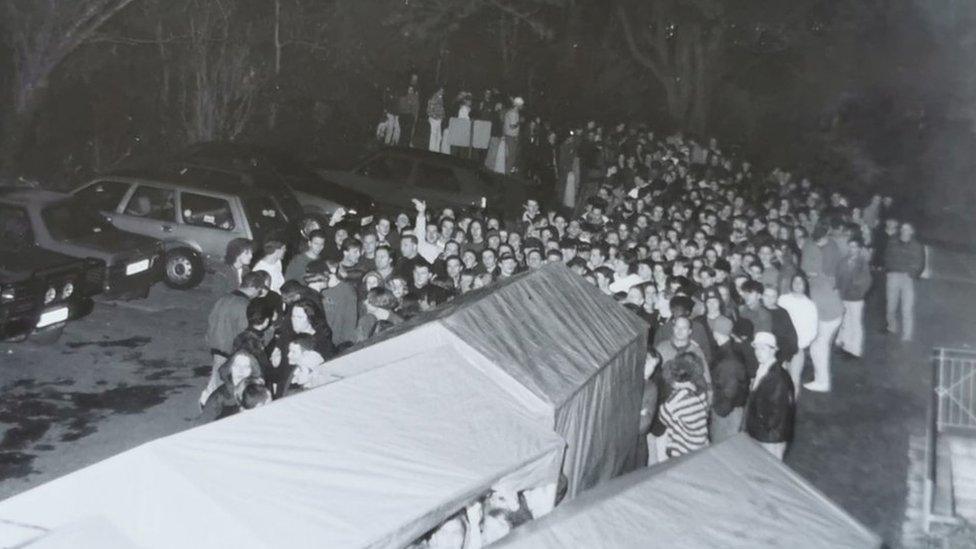

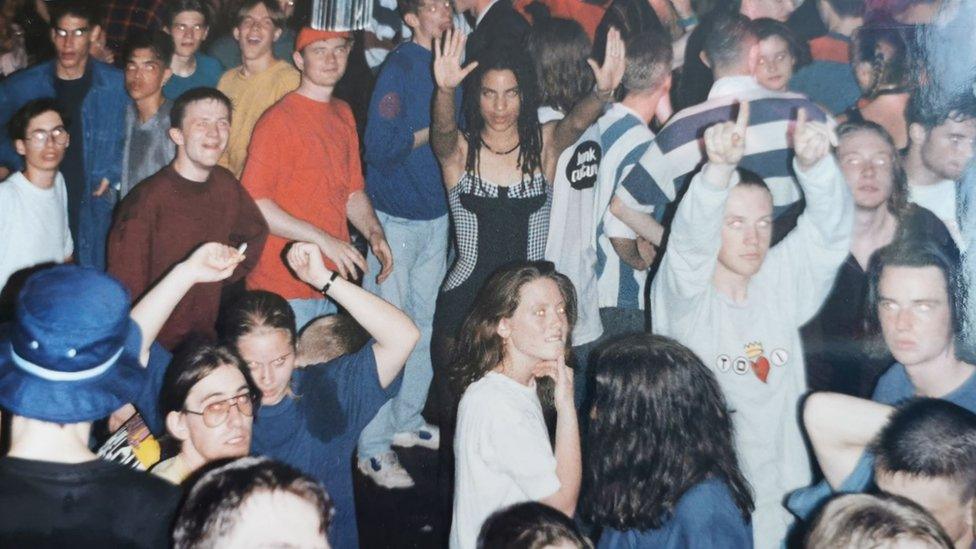

Sterns became hugely popular, with people travelling from all over the UK

Sterns reached people through flyers and word of mouth, bringing people down from London, Birmingham, Manchester, and even from across Europe.

Its location was undoubtedly unique - Jody Cottier remembers how they dug the basement of the house out of the South Downs chalk hillside, which insulated the huge sound system. Sweat and condensation famously dripped from the walls and ceiling, a phenomenon referred to by many as "Sterns rain".

"You walked downstairs and you felt the body heat coming up, and the sound was like being in a speaker," says Jody.

"It was a shared feeling, a buzz. Everyone was into music - it was anarchy on the dance floor."

Sterns hosted a number of acts that went on to become big names, including the Prodigy

James Holdsworth, who runs the Sterns Facebook page, remembers how relationships were built at the after-parties at Chaffinches Farm in Birdham - then home to the Interdance crew. He describes it as a "real, creative hub" where the best of the week's music was recorded at the farm's own studio.

Mensa prided himself on playing the newest music at the club, regularly travelling with Rachel to London to listen to pirate radio and recording music on cassettes to bring home because the reception on the south coast was so poor. At the club, DJs regularly accepted white labels from those in the crowd hoping to have their work played exclusively.

Former Sterns sound engineer Simon Scutt says Mensa's distribution of music, external "fresh off the turntable" helped spread the word about the club.

"He was very shrewd, very astute. It took a huge amount of energy. He'd drive thousands of miles. He distributed music as far as Scotland and abroad - and that music had only been heard at Sterns."

One flyer was based on the government's "Charley Says" children's public information films - although Sterns deliberately misspelled it

Sterns had three floors open to its members with techno on the top floor, garage and house in the middle and hardcore in the basement

Mensa's DIY aesthetic also extended to the club's unusual flyers, a 50,000 run which took all night to print. Tony Ladd, who designed many of them, says they hit on the idea to use household names such as Marmite alongside tongue-in-cheek wordplay to distinguish Sterns from other clubs.

"Using food and product-based ideas was a conscious effort to get the flyers to blend in nicely, as piles [of them] were distributed in shops and on counters in public places everywhere," he adds.

The club's popularity was to prove a double-edged sword. Each party was regularly attracting 2,500 people when it only had capacity for 900, says Simon, and cars would block the roads and were left parked on the central reservation of the A259.

Sussex Police already had Sterns on its radar over drugs concerns and the added attention from overcrowding fuelled the issue. Simon recalls how he and Mensa were arrested on Fontwell roundabout during a raid in 1992 when officers targeted cars approaching the club.

"We thought we were being robbed, but it was the police. They got us out [through] the car windows and they handcuffed us to each other across the top of the car."

Michael Hassanyeh and Nigel Bulloch captured the spirit of Sterns on film

Sussex Police says it no longer holds any records about Sterns but David Kenny, who has produced a 90-minute documentary about the club, says the 1992 raid was a game-changer.

"Once police started knocking on the door, it changed the vibe," he says.

"There were drugs, without a shadow of a doubt, but the way things got dealt with pushed them right underground. Closing the club doesn't tackle the issues.

"Those issues were freedom of expression and the music movement spreading through the country."

Sterns regularly attracted 2,500 people when the club only had capacity for 900

Councillor Steve Waight was tasked with visiting the mansion when he was elected. He said concerns about the club were nothing to do with the music, the clientele, or any kind of reaction to a youth movement.

The 64-year-old, who still sits on the Worthing and West Sussex authorities, went on to oppose renewal of the licence, which was awarded in 1990 when Mensa secured funding from Margaret Thatcher's Enterprise Allowance.

"I went up there with uniformed police officers and we saw open drug-dealing in the car park. My concern was solely the blatant and widespread use of illegal drugs."

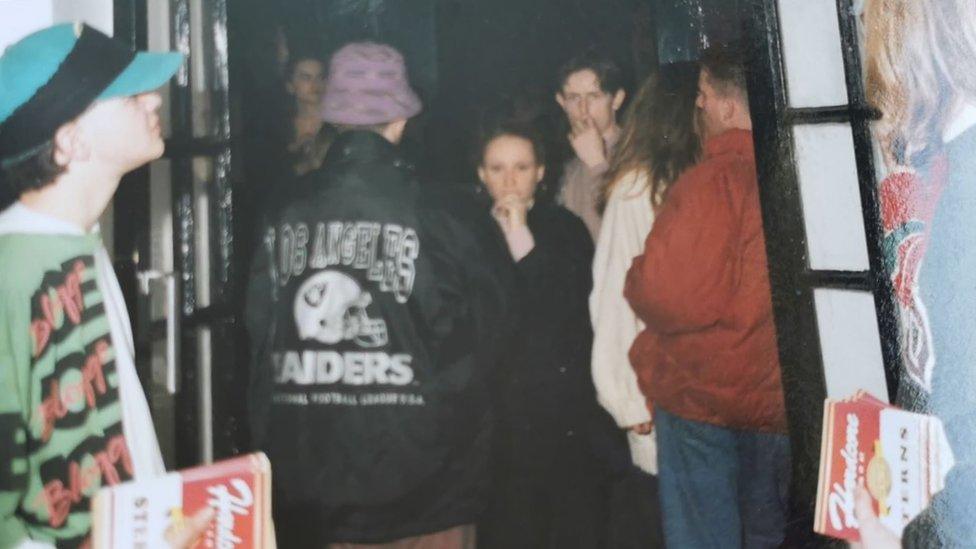

Revellers would often clog up the rural country roads trying to get to the venue

Richard Garrett fought the courts over the licence, telling magistrates that drugs searches at the club were so thorough he would have been embarrassed to undergo them himself. But ultimately, he failed to convince them.

Newspaper reports at the time cited a number of issues, including overcrowding and drug use. According to papers seen by the BBC under the Freedom of Information Act, Interdance lodged a further appeal with the crown court, but the legal bid was withdrawn.

Journalist Thomas Green, who lectures on dance music at the University of Chichester, believes Worthing Council has never wanted to celebrate Sterns, describing the town as small, conservative and, at the time, "offended by the club".

"They oppressed and crushed it. People involved with it certainly felt harassed. The law and council did not want it."

Punters remember how the mirrors and fluorescent paint of the basement somehow made the space seem larger

You might also be interested in

Others remember the heat of the club's packed rooms

Sterns closed before the Criminal Justice Act came into force in 1994. But its demise reflected the national disconnect between youth culture and the authorities.

Two years earlier, thousands of ravers had gate-crashed a free festival for new age travellers at Castlemorton Common - a situation widely viewed as the catalyst for what came next.

The then-Home Secretary Michael Howard had told the BBC the law wasn't designed to counter rave culture, but rather to balance one group of people's interests with another's. But this was also a Britain whose Prime Minister John Major had famously hit out at new age travellers, external and painted a picture of a nation that prided itself on warm beer and cricket grounds., external

"Sterns was the antithesis - dancing to loud music in an empathic and loving culture that was not necessarily based on people settling down," says Green.

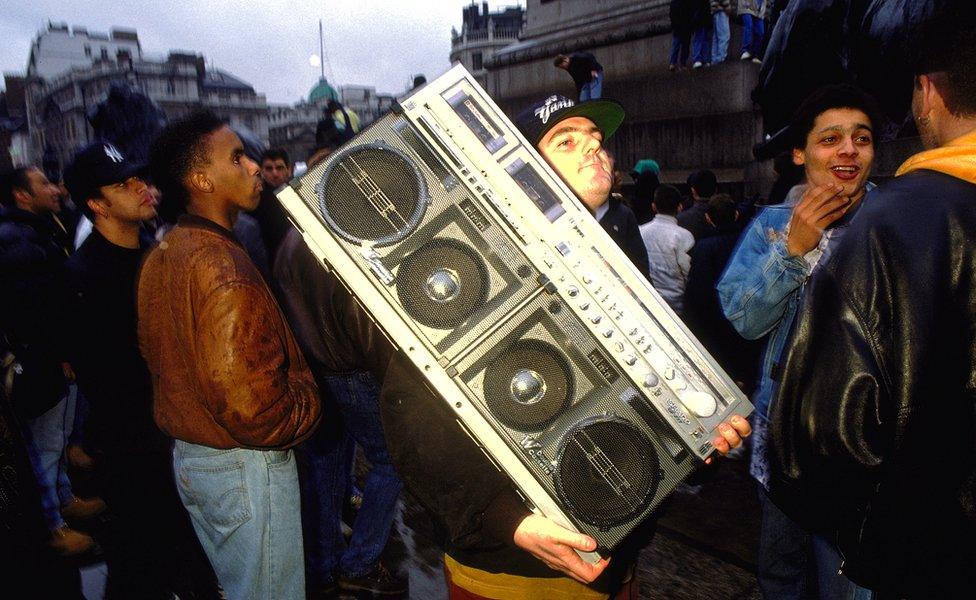

Protests against the Criminal Justice Act 1994 became known as "Kill the Bill"

Rachel remembers a feeling of belonging at the club

Sterns held its last party on 14 August 1993. Six months later, in February 1994, Mensa was killed in a car crash.

Rachel remembers how he had set off, only to return five minutes later because he had forgotten his Filofax.

"He joked and he said 'I love you, but only just' and off he went."

At the inquest, the coroner said Mensa - real name Adam Todd - had been overtaking, not wearing a seatbelt and speeding at 80 or 90mph in a 60mph area. His death from multiple injuries was ruled an accident, and a beer he had drunk at lunch was cited as a relevant factor.

Interdance ran a few more events in Bracklesham Bay, near Chichester, after Sterns closed and the club briefly reopened as Mansion House. But the party was over.

Jody, whose cousin survived the car crash, says: "When Mensa died, Sterns died with him."

DJ Carl Cox says Sterns was "100% equivalent" to Manchester's Hacienda club

The building is now a hotel, but memories of the south coast's tribute to the Second Summer of Love are fondly remembered by those who whiled away the nights within its walls.

Highpoints for Danny Bushell include the police helicopter descending in the car park to disperse ravers at noon - the day after the night before - and seeing Prodigy for the first time in October 1991.

"Entering Sterns was like opening a secret door," recalls another punter, Rob Ford. "Being in the house immediately gave you an energy many had never felt before."

Freedom to Party protesters marched through London's streets in 1990

Green describes what happened at Sterns as a "socio-music phenomenon" - something not seen since punk in the late 1970s.

"Sterns was a key place where people would come to dance to music made in people's bedrooms, music that was getting in the charts without being played on the radio: instrumental, electronic, minimalist music.

"We wouldn't have The Prodigy and the Chemical Brothers without it."

Filmmaker Kenny, who hopes to release his documentary pending licensing agreements, believes the energy that fuelled Sterns reflected a feeling of freedom and belonging.

"We should be hugely proud of what we were a part of," he says.

"But it happened too quickly. It was a moment in time. For a lot of people that was their moment in life."

A Sterns reunion will be held in Brighton on 24 August.

- Published28 May 2017

- Published12 August 2015

- Published14 March 2011