Whaley Bridge dam: The people who saved a village

- Published

More than 1,000 people have worked day and night for the past seven days to stop a reservoir dam collapsing and destroying a village in the Peak District. These are some of the stories of those who helped save Whaley Bridge from near disaster.

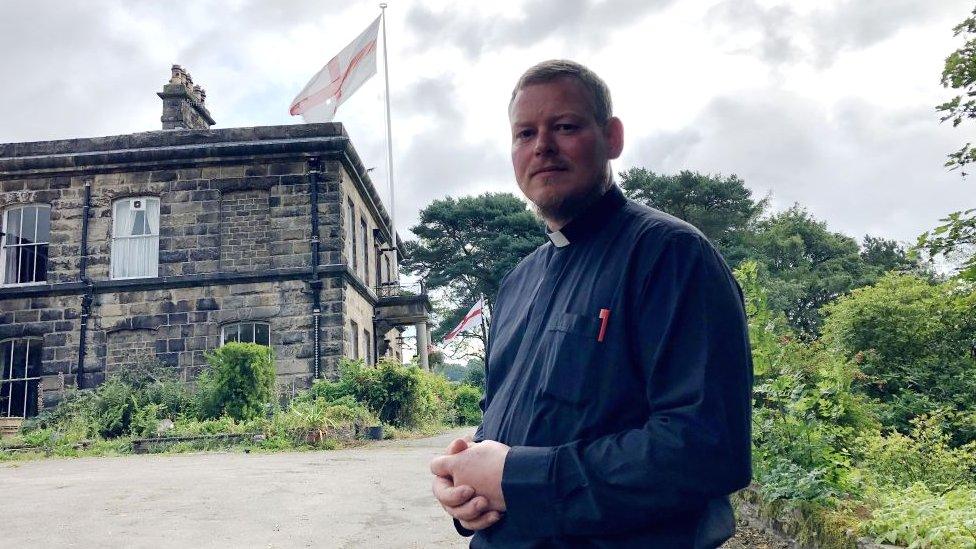

The vicar

Father Jamie Mcleod was the first person to raise the alarm

The reservoir at the bottom of Father Jamie Mcleod's driveway had never looked so full. On 31 July, the sight of the water cascading down the spillway was glorious, he thought.

But the flow kept getting heavier.

Early the next day, when the "bouncing" torrent turned yellow and water started to appear through the ground beside Toddbrook Reservoir, the vicar started to fret.

"I thought 'that's strange, I've never seen that before'," he recalls some six days later, sitting in a comfy armchair at his home, Whaley Hall, a church retreat house since 1979.

He went for a closer inspection and was horrified by what he saw - water coming through the concrete wall, not over it.

Toddbrook Reservoir: Footage shows fast-flowing before collapse

When he raised the alarm, Father Mcleod appealed to the authorities for one course of action - evacuate the village. When the order was given at about 14:00 BST, the SOS message he rang in Morse code on the church bells accompanied the wail of the emergency service sirens.

The clergyman would not sleep again for four days. As villagers fled, a wave of hi vis-clad construction workers and emergency service workers arrived, and he could see they would need feeding.

He put an appeal out on Facebook for supplies and a steady stream of donations and volunteers filtered down to him through the only accessible entrance - a rickety Secret Garden-style gate at the top of the church estate.

The vicar, sporting his dog collar, hiking trousers and red socks, wells up remembering the arrival on Saturday of a mother and her three-year-old boy, who held up his offering and said: "I have made a cake for all the people working on the dam."

Whaley Hall has been inundated with donations from other residents and shops

About 20 volunteers spent days making sandwiches, lasagnes, pies and baked potatoes in Father Mcleod's kitchen, which were then carried down to the sailing club - a makeshift respite area for those involved in the rescue effort.

His dining room has been overrun with boxes of biscuits, bottles of water and various microwavable meals, while his freezer is practically bursting with pizzas and his chairs creak beneath mountains of tea bags.

Father Mcleod has run the full gamut of emotions, from fear to sadness and ultimately relief as water levels and the risk of a collapse receded.

"It's been a very traumatic time but I do not feel as emotional now as I did. It hit me about two or three days in when I just burst into tears."

It was only after five days when the water level had reduced by 8m (26ft) he finally felt able to relax.

"Our spirits were lifted and we could actually smile and laugh again... Until then it had been very touch and go."

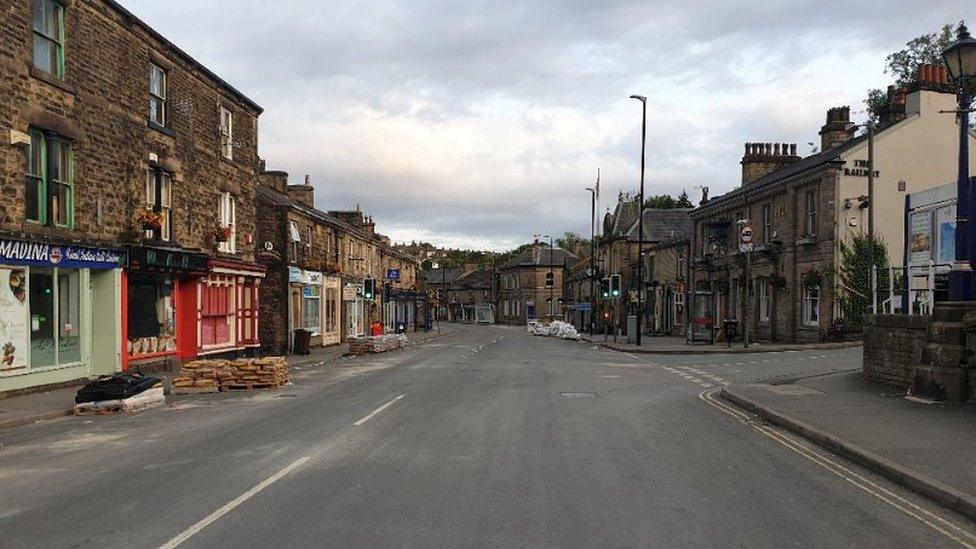

The centre of Whaley Bridge was deserted for six days

Though he has lived in Whaley Bridge for some 20 years, Father Mcleod says he has seen the village in a new light.

"I walked through on the Thursday night and it was a ghost-town. There were no sounds, no lights, nothing to say it was homey.

"But I have also seen the help for others that kicked in, the whole village came to each other's support, I have never seen that before in Whaley Bridge. The memories of that will never leave."

He has raised the largest St George's flag he can find "to show we are still standing."

And when villagers were finally allowed home six days after they left, they were welcomed by the chiming of the vicar's church bells.

The police

PC Tom Gee leads Derbyshire Police's drone unit

When the leader of Derbyshire Police's drone unit clocked in for work at 08:00 on 1 August, he could not have predicted his eight-hour shift would turn into a 27-hour stint.

Until last month, PC Tom Gee's team consisted of himself and one other person. Thankfully, they had recently trained up another 23 people.

"Well if we hadn't, we wouldn't have been able to offer the 24/7 service we have," he says, smiling with something resembling relief.

The drone has been "instrumental" in getting up close to the damaged dam and providing key information for making crucial decisions.

It was airborne within minutes of PC Gee's arrival on that first day, flying much closer to the precarious spillway than any human could safely get.

It was "quite daunting" and "by far" the biggest operation he has been involved with.

The drone footage allowed for closer inspection of the damage

"The severity had not sunk in yet. It was quite a scary thought as to what could happen. You could see bits crumbling."

The drone has clocked up more than 10 hours throughout the operation - a fair amount considering each flight is just a few minutes long.

"My main memory of this will be of not getting any sleep," says the officer. "It's been non-stop but that's why we do this job."

Deputy chief constable Rachel Swann said she placed officers' lives at risk every time they entered the exclusion zone

Meanwhile, the force's deputy chief constable Rachel Swann led the force in keeping the people of Whaley Bridge safe and updating the government as to the state of the emergency.

Her working day started as early as 05:00 and finished on almost every day well past midnight.

"It was a massive operation, the likes of which I don't think we've seen for many years," she said.

Ms Swann co-ordinated the evacuation, reassuring residents and trying to persuade those who would not leave that their lives were in danger.

She and her officers repeatedly went into the exclusion zone, knocked on people's doors and tried to convince people to go.

"Every time I placed an officer in that evacuation zone, I placed their life in danger," she said. "If the dam had gone it would have been catastrophic.

"When the dam was failing, you could literally see it failing before your eyes - people would have died."

The firefighters

Gavin Tomlinson has overseen the pumping of water from the reservoir by the fire service

The firefighters had a simple task in some respects: pump the water out of the reservoir before the pressure caused the dam to collapse, washing away the homes, businesses and school in the water's path.

But when they arrived, they could immediately see they needed help.

"My first thought was 'we are not going to be able to do this alone'," says Gavin Tomlinson, deputy chief fire officer for Derbyshire Fire and Rescue Service.

"We only have one high volume pump in Derbyshire. We needed 10."

Some 450 firefighters have been involved at Whaley Bridge

Within 24 hours, pumps from Wales and West Yorkshire, each with a six-person crew, arrived. Mr Tomlinson says almost the entire contents of the reservoir - some 1.5 million tonnes of water - needed to be emptied.

But even getting the pumps to the water was a challenge.

A road had to be built from the emergency services' makeshift command centre at Whaley Bridge AFC sports ground, across a small field, and through several hedges to the reservoir.

The fire service used 10 high volume pumps

"This incident could not have gone better for us," Mr Tomlinson says, his face now tanned from 16-hour days on site.

"They told us to get 8m (26ft) of water out and we said it would take a week. But after five days we have got 9.5m (31ft) out, so we have been ahead of the curve.

"This will be a blueprint for the country on how to deal with something like this happening again. Hopefully it's only a one-time thing."

The wing commander

Wing Cdr Gary Lane coordinated the military response

Three things needed to be done to save the dam.

Firstly, get the Canal Trust to close the inlets to stop any more water flowing into the reservoir. Secondly, empty the reservoir, which the fire service did. Finally, shore up the dam wall, which fell to the RAF.

If there is to be a defining sound of the crisis, it must surely be the thumping engines of the air force's Chinook helicopter, from number 18 Squadron based at RAF Odiham in Hampshire.

From 05:00 on Friday until Tuesday afternoon, the Chinook collected bags of aggregate from a hillside five miles (8km) away and gingerly dropped them into the breach in the dam wall.

The Chinook's rotor blades got as close as 3m (9ft) to the metal bridge at times

More than 450 bags, each weighing a tonne, have been placed with precision into the concrete crevice by a helicopter whose rotor-blades swirled just 3m (9ft) from a metal footbridge.

"I do not think it would get much more challenging than that," says Wing Cdr Gary Lane.

"The safety margins are at their finest."

Residents retained a sense of humour despite the impending disaster

It is all done by eye, with the three crew and two pilots aboard all having spent hours training themselves to recognise such finite distances.

The dam "is up there" as the largest job of Wing Cdr Lane's career, which has included responding to moorland fires, snowed-in Cumbrian villages and the aftermath of the Manchester Arena bomb attack.

"I got here on 1 August and I could see it was serious," he says. "Dealing with it was not impossible, but it was going to be very difficult."

The aggregate bags were attached to the Chinook on a hillside some five miles away

He says the "true heroes" have been the dozen or so members of the Joint Helicopter Support Squadron from RAF Benson in Oxfordshire who have laboured on the hillside, filling the bags of aggregate and hooking them to the helicopter for hours on end as it hovered just above their heads, its blades whipping up gusts of 70mph (110 km/h).

And in the back of his mind?

"The quicker you can get it done, the quicker they can get home."

The dam man

Daniel Greenhalgh has led the response of the Canal and River Trust, which is responsible for the reservoir

Daniel Greenhalgh is under no illusion as to how "extremely serious" the dam breach was.

"It was close," he says, exhaling heavily, as if he can finally afford time to breathe for the first time in six days.

"That dam had failed and if it had gone... well," he pauses, thinking, fearing, before adding with great understatement, "it would not have just been a flood."

Homes below the reservoir would have been swamped had the dam wall fully collapsed

The Canal and River Trust's north-west regional director knows an entire village would have been swept away had they not saved the dam.

He has been on site since 1 August, co-ordinating, strategising and ultimately making the decisions that could make or break the crisis.

"I'm sorry for the chaos this has caused. We have made it safe and have got a plan in place to keep it safe."

How events unfolded at Whaley Bridge

'I've never been hugged so much'

Whaley Bridge dam emergency in pictures

Mr Greenhalgh says every reservoir has an emergency draw-down plan: a list of actions to rapidly reduce water levels if they become dangerously high.

"This would have been a textbook draw down if the dam had not broken," he says, adding: "[The damage] complicated the matter."

It is not yet known how long it will take to repair the dam

He is full of praise for those he has worked with: the trust's contractors Kier, which built a road in just a few hours to allow fire service access; a Derbyshire County Council JCB driver who broke through a weir; the police officer who lined the dam with sandbags during the storm.

But his proudest platitudes are saved for the people of Whaley Bridge, in particular the volunteers who have provided continuous refreshments and humour.

"I have had to make a lot of decisions and been under great pressure," Mr Greenhalgh said. "I have been away from home, but going into the football club and being treated so well by the volunteers has made it feel like home.

"We have been surrounded by people who are rooting for us."

The volunteers

Julie Arnfield, Scarlett Tidmarsh and Tracey Longden are just three of the many volunteers

Whaley Bridge was effectively split in two by the evacuation - the sailing club and Whaley Hall at the north side of the reservoir, and the makeshift command centre at the sports ground to the south.

And on each side, a dozen or so volunteers congregated to provide supplies and food.

"The decision to help was spontaneous," says John Hind, development officer at Whaley Bridge AFC, whose pitch has become an impromptu helicopter landing pad and car park for a plethora of emergency vehicles.

Over at Whaley Hall, a steady stream of snacks and meals have been carried to the sailing club.

"I think the bacon sandwiches have proved the most popular," observes Julie Arnfield, one of the volunteers to respond to Father Mcleod's call to arms.

Volunteers were also on hand to give food to residents when they returned

"It was very scary. You could see it start to break up, you could hear it," she says. "I have found it quite emotional, but the community spirit has been second to none."

Pausing from prodding a tray of potatoes, cafe-owner and fellow volunteer Tracey Longden agrees. She recounts seeing the Chinook in action as like "a scene from a movie".

"It was just unbelievable," she adds.

About 1,500 people were out of their homes for six days

Almost everyone involved in saving Whaley Bridge from imminent disaster agrees that without the volunteers, the past seven days would have been far harder.

"The residents have been excellent," says fire officer Tomlinson.

"They have done just as many hours as we have," agrees PC Gee.

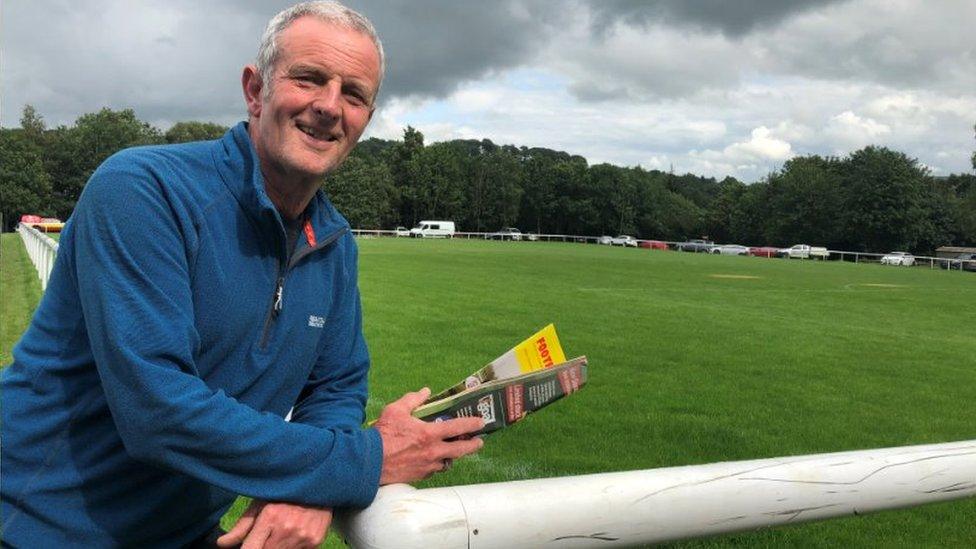

John Hind has been involved in Whaley Bridge AFC for 20 years

At the football club, Mr Hind seems bemused by the gratitude shown by all the workers.

"Everyone keeps thanking us but really that's the wrong way round," he says. "It's us who should be thanking them for saving our community."

Mr Greenhalgh is quick to offer more thanks to Mr Hind and many other volunteers, singling out a handful - Charlotte Pratt and Roz and Christopher Dranfield.

"We would not have been able to do what we have done without their support," he says.

"They too have saved their village."

- Published8 August 2019

- Published8 August 2019

- Published6 August 2019

- Published6 August 2019