Why Admiral's 'flashy' England strip now commands respect

- Published

It is 40 years since England's footballers first took to the field in Admiral's colourful reinterpretation of the national kit. Derided as garish and tacky, and almost abandoned after just a handful of games, how has it become one of the most-loved football strips?

As 90,000 flag-waving fans roared Land of Hope and Glory, the two teams marched on to the lush Wembley turf in a match the press had billed as "the Ten Million Dollar Kid meets Mighty Mouse".

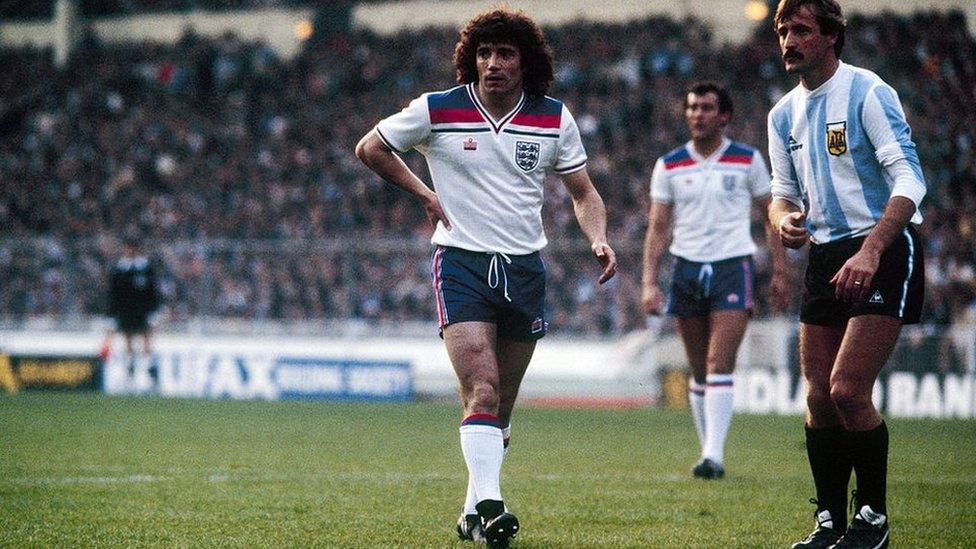

With teenage prodigy Diego Maradona in their ranks, reigning world champions Argentina were the home side's opponents on 13 May 1980 as Kevin Keegan once again donned the captain's armband.

"England tonight unveiling their new strip," announced BBC commentator Barry Davies. "Though quite why the England shirt should have the colours of the union jack remains a mystery."

The erudite man with the microphone was far from alone in his opinion, as the distinctive red, white and blue bands across the chest were a clear break from the all-white shirts the team had sported for close to a century.

The ensuing story of the strip - and of kit-maker Admiral - would mirror the national side's boom-and-bust fortunes and include a financial disaster which almost saw it shown the red card that very summer.

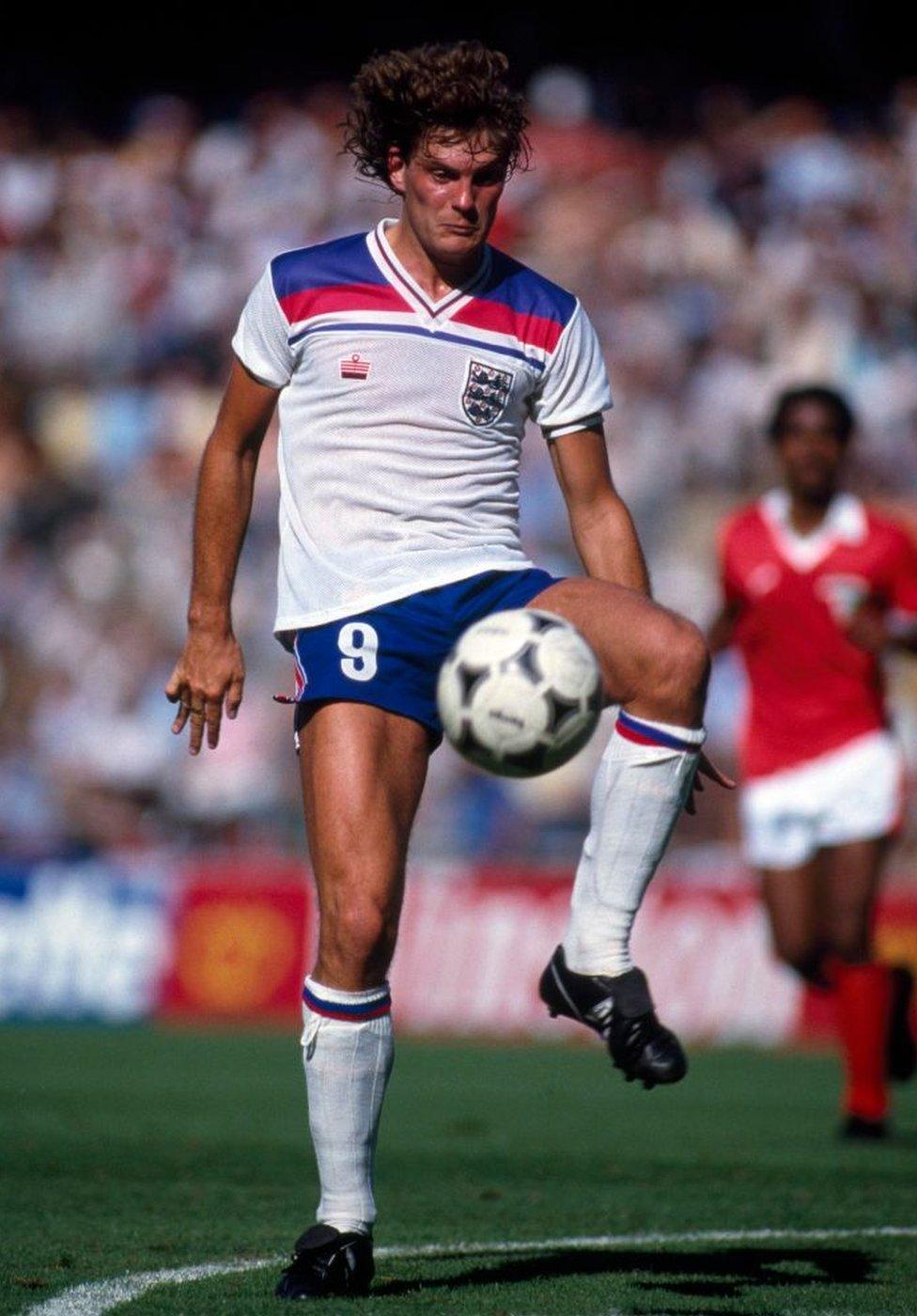

The strip will forever be linked to England's adventures at the 1982 World Cup in Spain

Much of the powerful Fleet Street media immediately showed disdain for the kit, which was the result of a £1m deal inked in 1979 between the Football Association and the Leicester-based firm.

When news of its impending launch broke in the Daily Mirror in January 1980, the pun-loving paper screamed "Strip off" and accused the company of "taking commercialism too far".

Springing to its defence in the Daily Express, Admiral owner Bert Patrick was adamant.

"England will be the best-dressed international team in the world," he declared.

Chosen from 60 subtly different designs, it had been the result of 12 weeks' work by a four-strong creative team, and The Sun splashed the first photographs across its front and centre pages at the end of February.

Keen to play up its exclusive, the publication reported the "shinier" strips were intended to impress under floodlights and on TV.

Those features would not be enough to placate Nottingham Forest boss Brian Clough, though. In a column for Match magazine, he bemoaned: "The wraps are off England's new kit - and I'm saying now I don't like it. It has the looks of one of my mother's old pinnies!"

This lightweight version of the shirt was flown out after the players had sweated heavily in the fierce Spanish sunshine

The media furore was nothing new to Patrick.

Revolutionising the kit market in 1973 when Leeds United became the first professional team in the country to wear a strip bearing a manufacturer's logo, his company had long faced accusations of profiteering.

In 1974 Admiral penned its first deal to provide outfits for the whole England team at an initial cost of £15,000 a year or a 10% royalty.

The addition of the firm's badge as well as shoulder stripes, trims and a switch to lighter blue shorts on that first strip did not go unnoticed.

"The FA's International Committee didn't really know what they were stepping into," Patrick says today.

"They agreed we could supply not only the kit but things like tracksuits and the medical bags, which had 'Admiral' right across the front.

"It had incredible publicity - I would say most of it bad - because the press thought an England team going out advertising a product was terrible.

"But it was like water off a duck's back. Those stories just helped create more sales."

Admiral's England deals saw Bert Patrick mix closely with the team's stars through the 1970s

Capitalising on the emergence of colour TV and young fans' desire to buy reproductions of their heroes' strips, the family-run former underwear firm landed deals to supply about 100 clubs as the decade progressed and kick-started today's multibillion-pound replica industry.

In the days before teams developed structured commercial operations, Patrick and the game's leading managers talked business over a glass of white wine from the comfort of his basement sauna.

Soon after the launch of England's 1980 kit, though, disaster stuck.

Days on from the side succumbing at that summer's European Championship in Italy, the Mirror made known: "Soccer kit firm's crisis".

Admiral, Patrick admits, "overstretched financially" in the face of fierce competition from rivals which had switched to cut-price Far Eastern labour.

"I was with the England team in Italy when FA secretary Ted Croker phoned me and said he'd had a call from one of our directors.

"They asked the FA to let me know the bank wanted us to call in the receivers and would I get back to Leicester as quickly as possible."

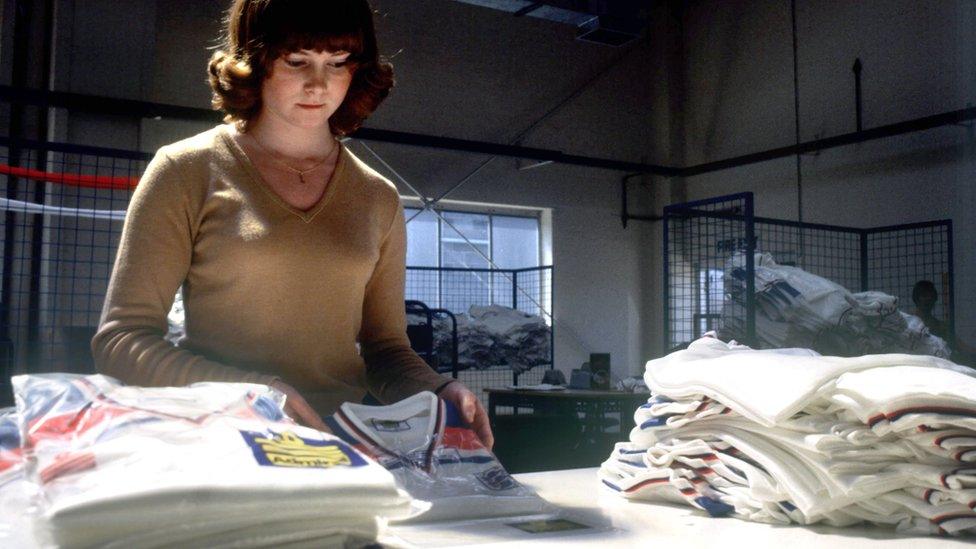

The 1980-83 shirt became the first England top to be mass produced in adult sizes

As England prepared to take on Norway in September, the same paper disclosed the team would "wear the controversial Admiral strip for the last time at Wembley tonight".

The kit had been shown off in fewer than 10 internationals across five months, but the FA was now free to find a replacement supplier following the firm's collapse.

"We were under attack all the time," says Peter Hockenhull, a businessman friend of Patrick who acquired the rights to the company's UK operations and fought "a huge battle" to reassure clubs, the FA and retailers it remained a going concern.

"Everybody wanted the flagship [England deal]. It was hard work getting the credibility back at the very beginning.

"I remember numerous times sales staff from another company used to tell retailers they were getting the contract. We had unbelievable pressure from Umbro, etc."

Among those to question his decision was BBC Two's The Money Programme.

"They wanted to know why I had taken this company out of receivership," he says. "I suppose it was the magic. The magic of the brand and the magic of England."

Where Patrick's Admiral had employed hundreds of people at its factories in Leicestershire and Ireland, Hockenhull outsourced manufacturing to other UK-based operations.

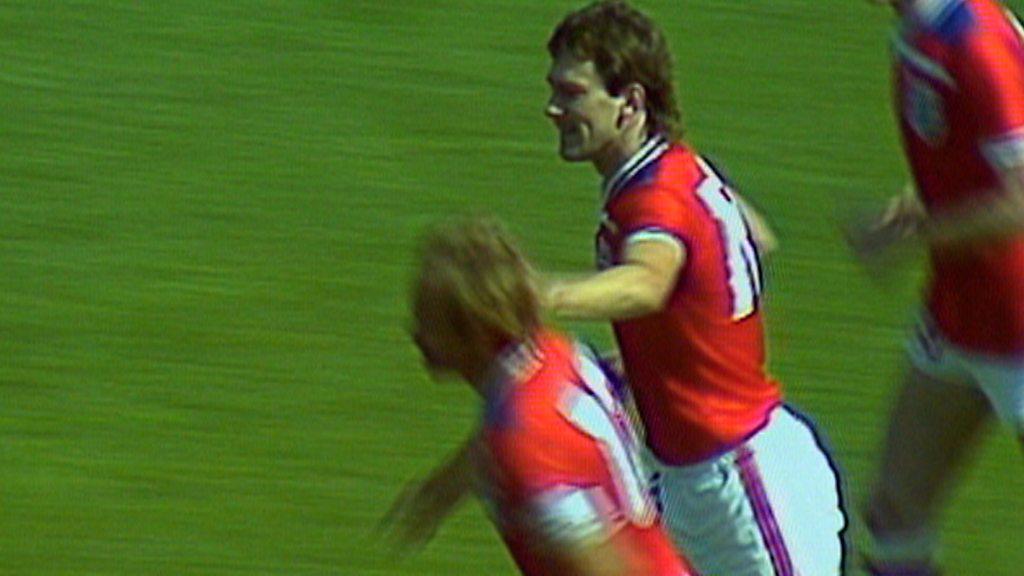

Wearing the red change strip at the 1982 World Cup, Bryan Robson scored after 27 seconds

In a qualifying campaign marred by terrace violence, England eventually secured their place at the 1982 World Cup by defeating Hungary in their final match.

The nervous new Admiral chief, without experience in the textiles industry, had an estimated £4m in sales riding on the result after paying hundreds of thousands of pounds for the rights to market themed merchandise.

"Because we were still in the embryonic stage of building the company back up, I genuinely wanted to pick the team," he says, a degree of tension detectable in his voice.

Shirt sales boomed on the back of the following summer's Spanish sojourn and expectations rose as Bryan Robson netted just 27 seconds into England's opening game against France for what was then the third-quickest goal in World Cup finals history.

While it would end in heartache as a squad featuring Peter Shilton, Trevor Francis and an injury-hit Keegan crashed out in the second group stage despite an unbeaten record, Hockenhull was enjoying a "Boy's Own Annual adventure", flying out a last-minute lightweight replacement kit and residing with the squad.

The following year, after selling his ownership of the rights, that thrilling ride was over.

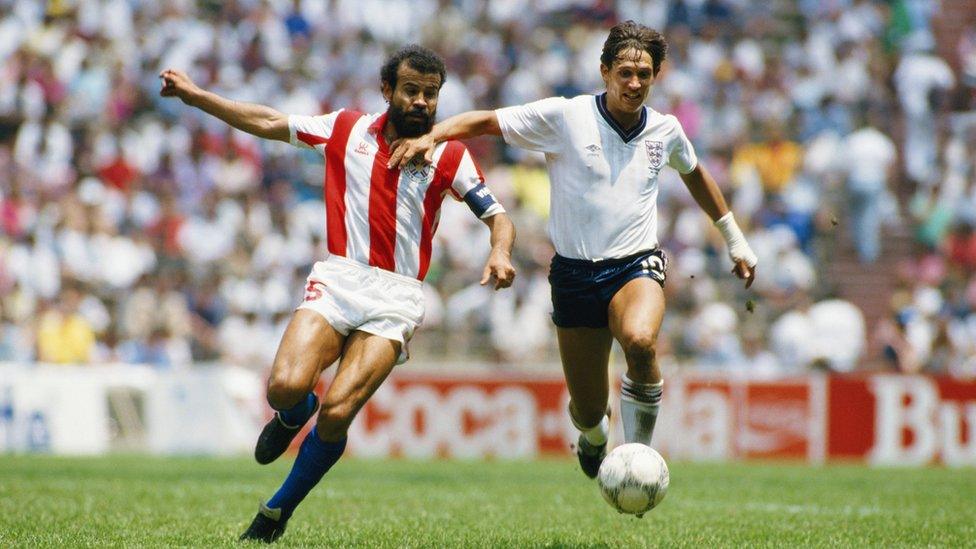

The strip, worn for the final time in November 1983 during an ill-fated European Championship qualification fixture in Luxembourg, received an ignominious send-off. Now led by Bobby Robson, England's hopes of reaching the tournament had already been dashed by table-toppers Denmark and once more hooliganism came to the fore.

Umbro immediately reverted to plainer white shirts but introduced a subtle striped pattern

Media opinion was still firmly against Admiral's efforts.

"FA get £1.5m to turn the clock back," read a Mirror headline in January 1984 as it explained the deal to produce "the current flashy strip" would be brought to an end, with World Cup winner Alan Ball weighing in to explain there was "no comparison" with the plain white jerseys of yesteryear.

When Umbro's replacement effort was unveiled the following month, The Sun excitedly told its readers the side were "reverting to a more traditional strip, throwing out the unpopular red, white and blue shirts".

"I still felt it was very England," an indignant Hockenhull says of the 1980-83 kit. "I never really understood why the newspapers were completely against it.

"They said it wasn't accepted very well by the FA, but it's not true. They embraced it. Ted Croker was happy with it, [then-manager] Ron Greenwood was happy with it and the players were happy with it.

"At the end of the day it was retailers who were going to promote it and sell it, and it was well received."

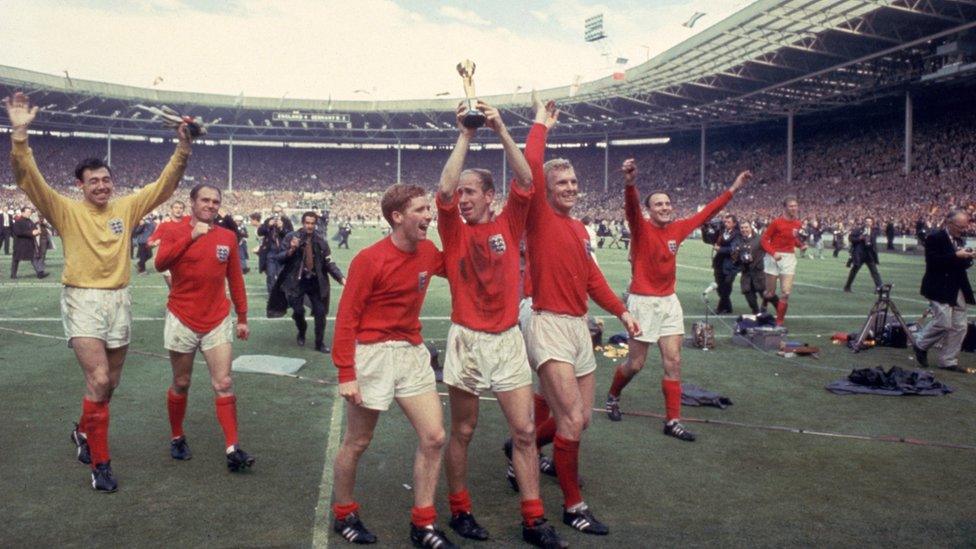

Having been mocked, today the strip is widely viewed as one of the team's best, alongside the plain red jersey worn at Wembley on 30 July 1966 and the diamond-patterned top of Italia 90.

Two years ago, current kit-maker Nike even introduced a warm-up shirt markedly influenced by Admiral's design.

So what led to such a dramatic reversal of fortune?

The red change tops of 1966 are an enduring symbol of English football's greatest triumph

Simon Shakeshaft, a curator of the National Football Shirt Collection who is penning an FA-backed book on England shirts, argues attitudes softened as kit changes became an accepted occurrence at club and international level.

He believes the "individuality" of the design, combined with England's achievement of qualifying for a first World Cup in 12 years and nostalgia for Admiral's "groundbreaking" efforts, elevates its status to that of a "classic".

"It's definitely a clean-looking strip. It dropped the wide collar [of the previous kit], was the first England shirt made from shiny material and had a very dynamic appearance. It was also bespoke. No other team wore that style.

"Anyone who grew up after the Admiral period may not understand what all the fuss is about, but the company's designers weren't tied to football history and tradition. They were instructed to create kits using certain colours but told it was more about the look.

"At one end you had the older traditionalists who despised it and said it was disrespectful, yet the children having it bought for them absolutely loved it. When you look back through Shoot and Match magazines the letters pages are filled with kids raving about it."

For a young Gareth Southgate, it would be his first England kit and helped create an abiding bond with the national side he now manages.

"I can vividly remember wearing it for football at school, football training on Sundays, in the garden and down the park," he says fondly.

"I chose it as a birthday present rather than toy cars or whatever else."

The red, white and blue design was not an issue for the many supporters who waved - and wore - the union jack in Spain in 1982

Such is the love for the strip now, and with an ever-growing collectors' market, vintage replicas are priced at £250 while players' match-worn World Cup tops can fetch £1,500. A jersey worn by captain Bryan Robson and autographed by his team-mates sold at auction for nearly £10,000 in March.

"When it comes to sought-after shirts, it's right up there with some of the best ever - the German shirt from 1990 and the Dutch one from 1988," Shakeshaft says.

"They don't come up very often, they really don't. But when they do they're in demand.

"The design was very much of its time and it's probably the England shirt with the least amount of white, yet it would top a lot of polls as their greatest of all time."

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published25 December 2019

- Attribution

- Published12 November 2019

- Attribution

- Published21 May 2019

- Attribution

- Published13 December 2016

- Published14 August 2014