Adoption breakdown: 'No support' for violent children

- Published

The parents said finding support for their traumatised children was incredibly difficult if not impossible

Heartbroken mothers have described the anguish of returning their adopted children into care after they became violent.

The women felt they had "no choice" but to give up their children because of the difficulty of getting any support.

The government said "many children leaving care will have experienced trauma".

Psychologists have called for better assessment for children and specialist training for parents.

The charity Adoption UK said about two-thirds of adoptive parents encounter aggression or violence from their children, while a lawyer specialising in adoption cases told the BBC his firm got referrals from all over the country from families who felt lacking in support.

Some names and details have been changed to protect the identity of the interviewees.

'I needed treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder'

Marie said "the worst thing was the verbal abuse" she received from her adopted daughter

Marie adopted as a single mum and said she had no idea she "would or could" become the victim of violence and verbal abuse from her daughter.

"There were times when it didn't feel safe for either of us," she said.

"She tried to jump out of an upstairs window saying she wanted to die and I was trying to restrain her.

"On another occasion she went to the kitchen drawer and took out a knife and asked me to kill her."

Marie was headbutted and kicked in the stomach by her adopted daughter as well as receiving verbal abuse.

She did not want to give her daughter back but said in the end she felt there was nothing else she could do.

"I'd been fighting it for quite a while, several people suggested that would be the best option, they were saying 'no-one would blame you' but I did blame myself.

"It took me several years and treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder myself before I forgave myself for that decision," Marie said.

"I just didn't have a choice I just couldn't carry on."

'Returning my daughter ended my career'

Claire said "the most vulnerable children in society are placed with our families and then social services and the local authority just walk away"

Claire felt like she was unable to keep her adopted daughter safe.

"The police would bring her in through the front door, she would climb out of her window and the police would be looking for her again," she said.

On two occasions she had to call the police because her daughter was destroying items in the house, smashing windows and being threatening.

"Police reports show that they could hear her screaming and swearing at me in the background when I was on the phone to them," Claire said.

When court proceedings began to return her into care, Claire's daughter had a psychological assessment and the report said "love was not enough".

"I had a career in education that I could not carry on because I'm seen as an abuser because my daughter has gone back into the care system," Claire said.

"There's no allowance for the fact I'm not her birth mum, I didn't cause this trauma, I was simply trying to do the right thing by her and offer her a stable, happy family life."

'I don't think it would have been any harder if my child had died'

Linda said "when you're intensely caring for a child who is so traumatised, everyday there's a new trouble"

Linda adopted her child as a toddler but eventually returned them into the care system after 12 years.

At first they were only violent to older children but eventually the situation became too much to bear.

Child and adolescent mental health workers said their behaviour was too extreme to be treated.

"When I look back I really don't know how we've survived, any of us," Linda said.

Linda blames her child's violent and difficult behaviour on traumatic experiences they had gone through before being adopted.

There was a history of neglect and abuse in the family home where Linda's child once lived.

Linda said she would always feel responsible for her child.

"I don't think it would have been any harder if they'd died," Linda said.

"I wish my child never had to have those first two years with their birth family.

"Maybe if they'd have come sooner they'd have been less damaged."

How common is adoption breakdown?

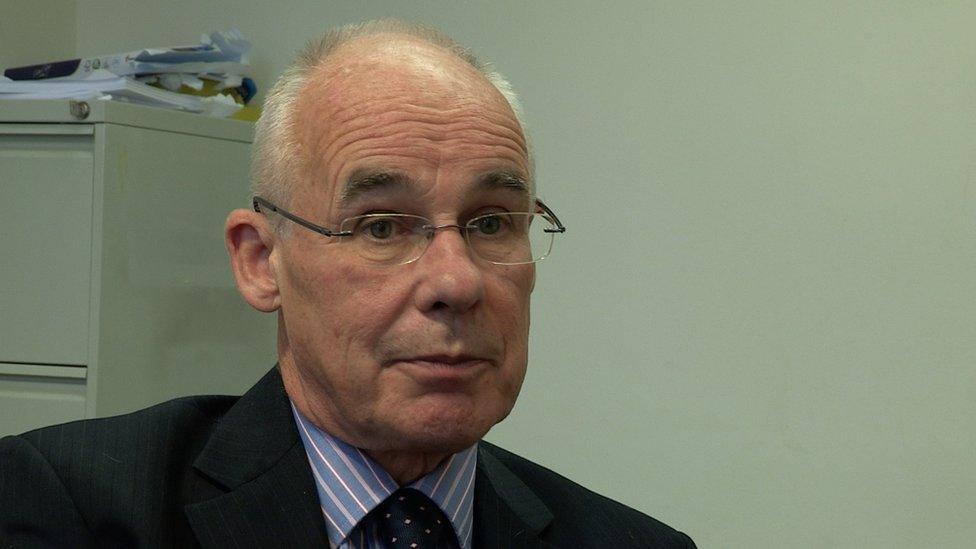

Lawyer Nigel Priestley described adoption breakdown as "a very significant problem"

According to Adoption UK, up to 65% of adoptive parents experience violence or aggression.

In 2014, the first national study of adoption breakdown put the figure at about 3%.

But a lawyer who specialises in adoption cases said that was "probably understating the problem".

Nigel Priestley said: "We get referrals from all over the country and many parents are finding the support they desperately need simply isn't there for them."

The Department for Education does not collect official statistics on adoption breakdown.

A spokesperson said: "We recognise that many children leaving care will have experienced trauma in their lives and will need support to help them thrive in their new families.

"Every decision regarding adoption is made with the best interests of the child at heart and is always based on the individual child's needs."

What can be done to help adopted children and their parents?

Dr Renee Marks said trauma can affect a child's capacity for interpersonal relationships and make some youngsters unable to reflect on their own behaviour

Families can currently apply for grants of up to £5,000 for therapy from the government's adoption support fund.

Specialist therapist Dr Renee Marks said trauma affected the way a child's brain developed.

The earlier a child encountered a traumatic experience, the more profound the impact would be on the brain.

"I think the children need to have a full assessment in terms of their psychological needs and level of trauma prior to the placement in adoption," she said.

"Adoptive parents have to know exactly what they are going to have to encounter, they need specific training for that child."

Sue Armstrong-Brown, the chief executive of Adoption UK, said there was a growing understanding of the support parents and children required but a "completely fit for purpose" adoption system was still needed.

"When we do have one it will be completely child-centred and put the need for support to recover from trauma at its heart.

"That will look like every child having an assessment of need at placement and regularly afterwards," she said.

"It will look like a support plan that follows the child around, that's fully resourced throughout their lifetime.

"It will look like much better support and information for families from the start."

If you or someone you know has been affected by adoption issues, help and support is available at bbc.co.uk/actionline

Inside Out examines adoption disruption on BBC One at 19:30 GMT on Monday 28 October and can also be seen afterwards on the iPlayer.

- Published14 October 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published8 October 2019

- Published23 August 2019

- Published2 July 2019