Max and Keira's Law: Transplant stories as law changes

- Published

After the transplant, Hannah Sharma did what she always wanted to do - buy a puppy

Organ donation will now be automatic in England unless people opt out, in new laws which come into effect today and could save up to 700 lives a year. Four people whose lives have been touched by the transplant scheme share their stories.

'It's mine, but it's not mine'

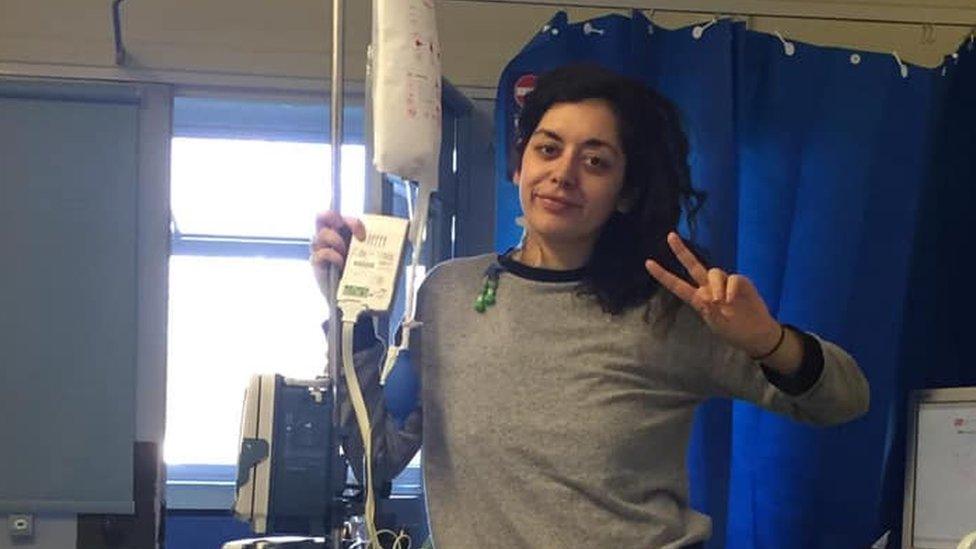

Hannah Sharma said the transplant offered her a way to live her life

Hannah Sharma went into hospital last year with what she thought was a chest infection only to discover she had heart failure.

Until then, she had been fit and healthy but it is now thought she might have had a viral infection called dilated cardiomyopathy.

Hannah, from Mayfield, East Sussex, had several hospital stays including a spell in intensive care as she fought off infections, but eventually became so ill she knew she had to prepare herself for the "long haul".

By the time her consultant mentioned a heart transplant, the 29-year-old said it was almost a relief. But it wasn't without setbacks - she waited in hospital for about six weeks, in which time two hearts became available, only neither were a suitable match. By the time the third call came, there were no nerves, just excitement.

"We listened to songs and we were dancing in the room," she said.

The operation took four-and-a-half hours and she came around from the anaesthetic the following day.

"I remember sitting in my bed and hearing it, [thinking] I hear my heart. It's so loud. It's mine, but it's not mine. I can never get my head around that."

Hannah Sharma knew she was in hospital for the "long haul"

Within 24 hours, she was out of bed and sitting on a chair. The next day the physiotherapists had her marching on the spot.

A week after the transplant, she fulfilled a long-held ambition and sent her sister out to buy her a dog. She met Huey the sausage dog on FaceTime from her hospital bed, and two-weeks post transplant, the pair were united when she was discharged.

"I'd wanted a dog for a very long time. My mum was like 'you can't have a dog', but I was saying 'I need to do it now. Life's here now.'"

Ms Sharma said the future is "tricky". She can suffer side effects from the medication and has good days and tired days - and there is always the risk of organ rejection at any time.

She says during recovery, she spent a lot of time thinking about her donor - a 55-year-old woman whose family she will soon write to.

"Life is very different to how I saw it, but I try not to dwell on those things and live as much as I can while I'm fit and healthy," she said.

"Some people live 35 years post-transplant, so I could still have a lot of years. It is scary, but it could have completely stopped last year... so I'm thankful for any time I get."

'It's not fun, but it could be worse'

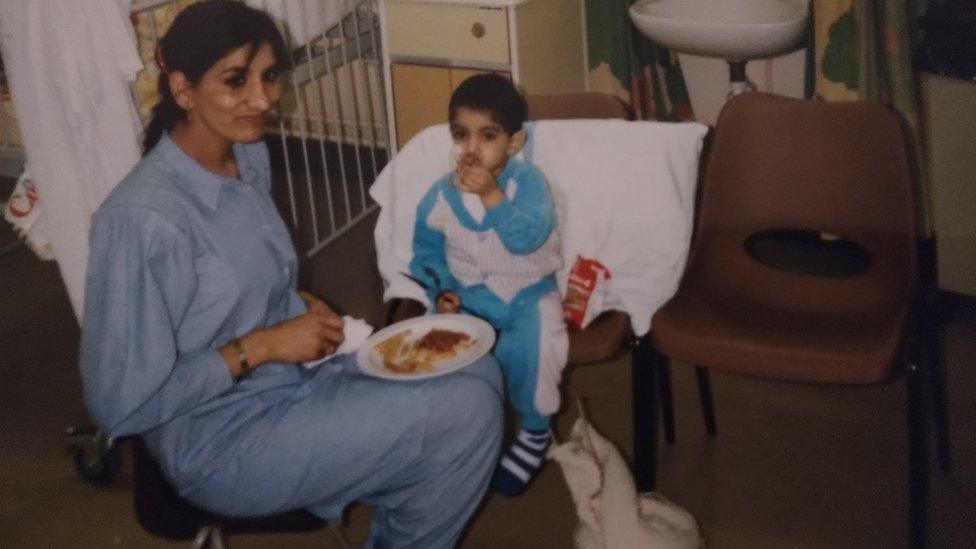

Fez had his first kidney transplant at age three and is now waiting for his third

Faizan Awan was born needing a kidney and can't remember having his first transplant at the age of three, but remembers realising at a young age he was different to others his age.

Growing up, he could not join in sport and while his friends were at the cinema, he would be on his dialysis machine. At 14, he had a second operation and received a kidney from his father.

The average lifespan of a donor kidney is between 10 and 15 years, according to the NHS, and 34-year-old Mr Awan is on the list for a third time, although he and his family are matter-of-fact about it, as they know what to expect.

"Until then, there's not really much you can do but wait."

You might also be interested in:

Mr Awan had his first transplant at the age of three, after which he could eat solid food for the first time in his life

Mr Awan said he has has been waiting for an organ for five years because there are fewer donors among ethnic minorities. He hopes the legal change will improve his chances and encourage people in South Asian and Muslim communities to talk about the subject more openly.

"Part of it is generational bias," he said. "My grandparents and great-grandparents didn't [donate] in Pakistan - that's the norm when family move without fully understanding the system is different here.

"In Islam, there is a lot of text that can be translated for or against transplants. There is no literal line that says 'yes it's allowed' or not."

Mr Awan is now an organ donation ambassador for the NHS and volunteers for the Lancashire and South Cumbria Kidney Patient Association, where he helps other patients and carers deal with kidney disease, dialysis and transplants.

"It gives people some kind of comfort knowing it's not the worst thing in the world," he said. "It's not fun, but it could be worse."

What is changing?

From Wednesday, all adults in England will be deemed to have given consent to donate their organs when they die, unless they have opted out, or are in an excluded group.

The new law, known as Max and Keira's Law, has been named after two children.

Nine-year-old Keira Ball saved four lives, including that of Max Johnson, also nine, after her father allowed doctors to use her organs for transplants after a car crash in 2017.

It has been estimated that the law change will lead to an additional 700 transplants each year by 2023.

'Organ donation is an open conversation'

The sisters have established an ethical womenswear brand

Two years ago, Laura Beattie was given the news she had been expecting for some time - she would need a lung transplant.

The 31-year-old was born with cystic fibrosis, a life-shortening genetic condition that can cause fatal lung damage. In 2016, she became more breathless and her condition worsened, leading to her taking the tests to go on the transplant list.

Since learning she would need a transplant, Ms Beattie has spent time preparing for the procedure with an NHS transplant team of experts and psychologists.

"I was probably in denial. I try my best at everything. I was just feeling upset with myself. And I was scared. I'd never had a proper operation before.

"You work towards it. You have every test imaginable so they can match up the organ with you. And it's just about keeping busy and focused and trying to see the best in myself.

"And there are mixed emotions, which can depend on how you feel each day."

One distraction is her online fashion business, which came about because she had struggled to find dresses to fit because her rib cage is slightly larger due to her condition.

Her sister, Rachel, then 14, came up with the idea to so start their own brand and a decade on, they work with teams in Manchester, Italy and Portugal.

Ms Beattie said: "It's about determination and never giving up. I work hard with my treatment and keep myself stable, and with the business it's the same.

"It's about never giving up. It's about coping with setbacks and knowing you can get through."

Ms Beattie, from Manchester, hopes the law change will improve her chance of finding a match but acknowledged that her survival relies on someone losing a loved one.

"Organs come from someone who has died and talking about that side of it is scary. But I think the more [organ donation] is spoken about, the more it's an open conversation."

'She saved a life'

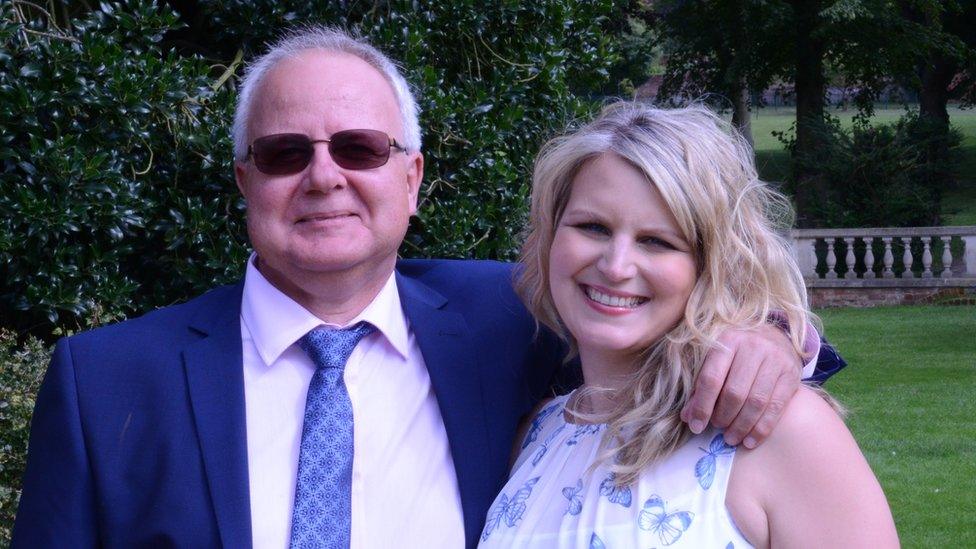

Keith Astbury said his daughter, Pippa, lived for her son and "cared about everything"

Two years ago, Keith Astbury lost his daughter Pippa to an instant, catastrophic, brain haemorrhage.

She was placed on a ventilator but he already knew the situation was not hopeful. Several hours later, he discovered his daughter had signed up as an organ donor via three different media.

"We thought if that's what Pippa wanted, that's what's going to happen," said the 70-year-old from Trafford, Greater Manchester.

Pippa died in 2018 and since then, her family has received a letter they described as both "heart-warming" and "bittersweet" from the recipient of her lungs - a mother-of-three whose life was saved by the transplant.

Both families exchanged letters in a process that brought comfort, said Mr Astbury, who is now an NHS organ donation ambassador.

He described his daughter, who would have turned 43 today, as a mother who lived for her son, and a "people's person" who cared about everything - so much so she had decided to retrain as a social worker.

"Pippa's organs didn't go to waste," Mr Astbury said. "She saved a life and we feel part of Pippa is still living and still with us."

- Published20 May 2020

- Published26 February 2019

- Published24 October 2019