'My dad gave me his kidney and saved my life'

- Published

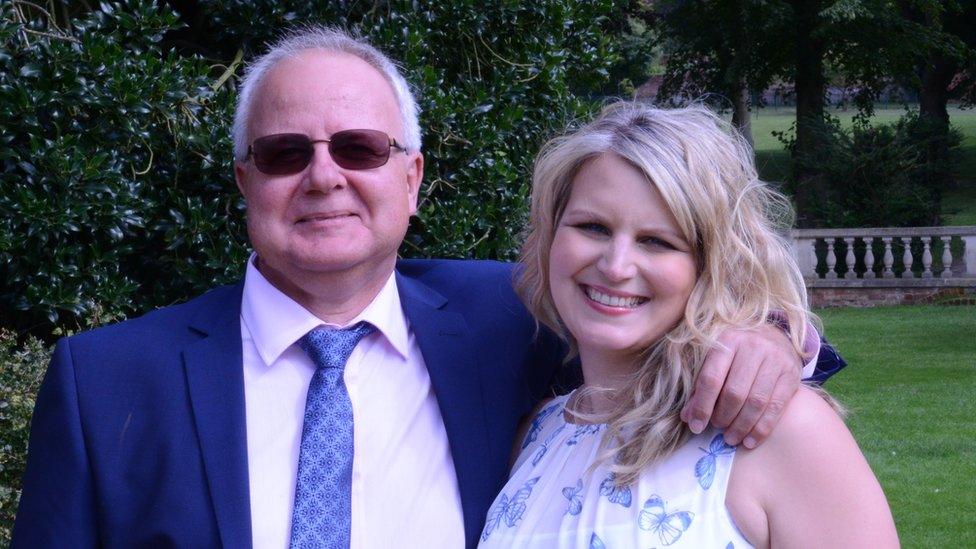

Samantha Dalton says her dad Barry is the hero of her story

Two days after her wedding, BBC journalist Samantha Dalton found out her kidneys were failing. Within a year, she needed a transplant. In stepped her dad, Barry.

Samantha

Six months ago, my dad gave me a second chance at life. It sounds like a cliché, but that's exactly what donating a kidney does for someone with kidney disease. It gives you the chance to hope; the chance to return to something resembling a normal life.

It started two years ago - two days after I married my wonderful husband, Justin. We were driving to a friend's house; it was a lovely late summer evening and we were due to fly out to Austria early in the morning. Then the phone rang.

My GP had recently asked me to come in for some blood tests after a routine check-up showed I had high blood pressure, with no obvious cause.

"I think you need to head to A&E as soon as possible," my doctor said. "Your kidneys might be failing."

I was 34. And they were right, my kidneys were failing, and had been slowly, for a number of years, and I hadn't had a clue.

Various tests showed I had a disease called IgA Nephropathy, also known as Berger's disease, external. Over time, a fault with an antibody called IgA had caused damage to the tiny filters of the kidneys, which strip the blood of toxins and excess liquid and turns it into urine. Worst of all, there is no cure. At a point in my life when I was looking to the future, everything started to fall apart.

Medication to treat my blood pressure, which was high because of the damage, helped stabilise my kidney function for a while. I was able to go on honeymoon to Australia and lead a pretty normal life, although the fear of kidney failure was constantly in the back of my mind.

Samantha and her husband, Justin, were able to enjoy their honeymoon in Australia before the transplant

Then it happened - in May 2018, my kidneys started to decline rapidly. My consultant put me on a gruelling regime of corticosteroids to ease the inflammation but I suffered badly with the side effects. I couldn't sleep, gained weight, suffered terrible mood swings and developed the dreaded moon-face.

This was, by far, my emotional low point. I was ashamed of my appearance; I didn't want to look in the mirror, or be photographed, or see anyone that I hadn't seen for a while because of my fat face and swollen tummy. The regime only lasted six weeks but it felt like an eternity and I was miserable. It sounds perverse, but it was almost a relief to be told the treatment wasn't working and I would need a transplant.

As we drove home to Chrishall, near Cambridge, from the hospital, I called my parents: "It's not worked, I'm going to need a transplant soon."

"Tell us who we need to talk to, and we'll start the testing," they replied.

Justin and my sister, Laura, were also willing to be tested. I was grateful and humbled - many people are terrified to ask loved ones whether they'd consider giving up a kidney, but my amazing family were prepared to do it, no questions asked. My dad was most insistent; he was determined it would be him.

"The dreaded moon-face" was Samantha's low point

The tests revealed he and I were different blood groups and for a short time the transplant was in doubt. It was tough trying to stay positive but we were rallied by the results of the tissue typing, which revealed our kidneys were a perfect match. I'd need a procedure to wash my blood in the days prior to the transplant, but we were back to feeling elated.

We were given a date in early April and I mentally ticked off the days until the operation. During this time the effects of end stage renal failure started to kick in. I was battling fatigue; a constant exhaustion that no amount of sleep could quench. I forced myself to exercise, to continue to work full time. I used the little energy I had to stay upbeat, aided by the constant love and support from family and friends, which kept me going on the darker days.

On the day of the transplant, I remember walking to the operating table in my surgical gown, lying back, and looking at the bright lights overhead as the general anaesthetic took hold. The first thing I remember seeing when I came around was the clock on the wall, then the faces of the team in recovery, who were monitoring all the drips, drains and lines attached to me. I felt overwhelmed but ecstatic - it was done. I even waved at one of the surgeons who walked past my bed. Could life now begin again?

Three days after the operation, Samantha started to feel "brighter"

My family were waiting for me on the ward - it had been an excruciating day for my mum Mandy, and Laura, who had us both under the knife at the same time. It's obvious what my first question was: "How's dad?" His surgery had taken slightly longer than expected but he was awake and in the next ward. The relief swept over me; for the first time in a long time, it felt like things were looking up.

We had hoped the kidney, who we named Billy, would start to work straight away. The following day, my blood tests showed it was working brilliantly, filtering the waste products from my blood and instructing my bone marrow to start making red blood cells.

I was in hospital for about a week and by about day three I was feeling brighter. I had also lost the strange feeling that comes with kidney failure - like the insides of your body are attempting to push outwards; a pressure which drains your energy and clouds your thoughts.

Recovery was rapid. I quickly populated my list of post-op "firsts": first solo shower, first dog walk, first glass of wine. I was jogging by about eight weeks and back to work at BBC Look East by week 12. My energy had returned - I didn't feel exhausted by lunchtime, my skin and eyes were bright and I felt normal, despite the daily cocktail of drugs to prevent my immune system attacking the kidney.

The side effects can be difficult to manage, but so far I've not been badly affected. I will need immunosuppressants for as long as the transplant lasts. The NHS says the average lifespan of a living donor kidney is about 15 years, so it's likely I will need another in the future, but hopefully by the time that happens, science might have advanced to the stage that kidneys can be grown in a lab.

My dad is back to his old self - back to work and back to shouting at the TV when West Ham are playing. People tell me, "you're so brave", but I'm not the brave one, my dad is. He's the hero of this story and I tell it to honour him.

Barry

Barry Dalton said he "knew it needed to be me" when his daughter learned she needed a new kidney

Discovering your child has an incurable disease is a nightmare for any parent. From the point we discovered Samantha would need a transplant, I knew it needed to be me - it was my job as a father to look after her. I also felt it was my right, it wasn't a duty or an obligation, just a desire for her to have as good a life as I had; it's what any father wants for their child.

I also didn't want Mandy, Laura or Justin to go through the operation. Laura and Justin especially would have to live for longer on one kidney and, at approaching 60, I had lived more of my life. It was a risk worth taking.

The first of six appointments at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge was to assess if I was generally healthy enough to donate; the others were more technical. I had my heart monitored, tests to measure my kidney function, scans to see which kidney would be best to take and lots of blood tests.

The most brutal part was not the physical testing, but the emotional one. Sam and I had a compulsory meeting with the Human Tissue Authority, the regulator which ensures organs and other human tissue are removed for the right reasons. Talking about why I wanted to donate was easy but the hard part was when we were brought into the room together and Sam was asked how she'd feel if I passed away during the operation. Seeing her so concerned and upset made me feel so sad. I didn't want her to feel that it was her fault if anything bad happened to me.

Barry just before his surgery

In the few months until the surgery, I would turn 60 and celebrate my 40th wedding anniversary. However, I didn't feel like I wanted to celebrate; my mind and thoughts were totally consumed by getting the operation done and it being a success.

Friends and family made it easier. I kept myself busy with work and I continued my hobby of salsa dancing as normal. I went out a little more than usual, my buddies even took me out for a "goodbye kidney" party.

The operation came around quickly. The transplant team was excellent and the doctors gave me a lot of confidence that I'd be OK. The keyhole surgery took a little longer than expected but when I woke up in recovery, the relief flooded over me. My part was over.

You might also be interested in

Living next door to mum and dad

The homeless teen who studied by candlelight

I didn't see Sam until the next day, when I forced myself to hobble over to her bed. Although she looked a bit worse for wear, her blood tests were good and I was glad my efforts hadn't been for nothing - plus I wanted her to see I was OK.

The recovery took a little longer than I expected - it felt like a herd of buffalo had trampled my insides. To remove a kidney, your abdomen is blown up with gas to allow the surgeons to manoeuvre their instruments more easily. But this stretches your skin and muscles and leaves you in a bit of discomfort for a couple of weeks afterwards. It was about four months until I felt normal, although I returned to work part time after about eight weeks. I forced myself to walk every day and it wasn't long before I returned to salsa.

Barry feels honoured to have transformed his daughter's life

Living organ donation is not for the faint-hearted but if you're able to and fit enough, do it. It's absolutely worth it, especially when I see Sam doing so well, with colour in her cheeks and a sparkle in her eyes again.

I still get emotional about it - that will never go. When people say to me, "you're a hero", I smile but I don't consider that to be the case. I know I've been able to give Sam a life worth living - I feel good about it, but I did it because I wanted my daughter to be well, not for any other reason.

Six months on, I have no regrets. My life is now complete; I don't feel I have anything to prove and part of me feels privileged I've been able to this. Not everyone has the chance to transform someone else's life.

- Published9 June 2019

- Published20 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019