COP26: Where have emissions fallen the most in England?

- Published

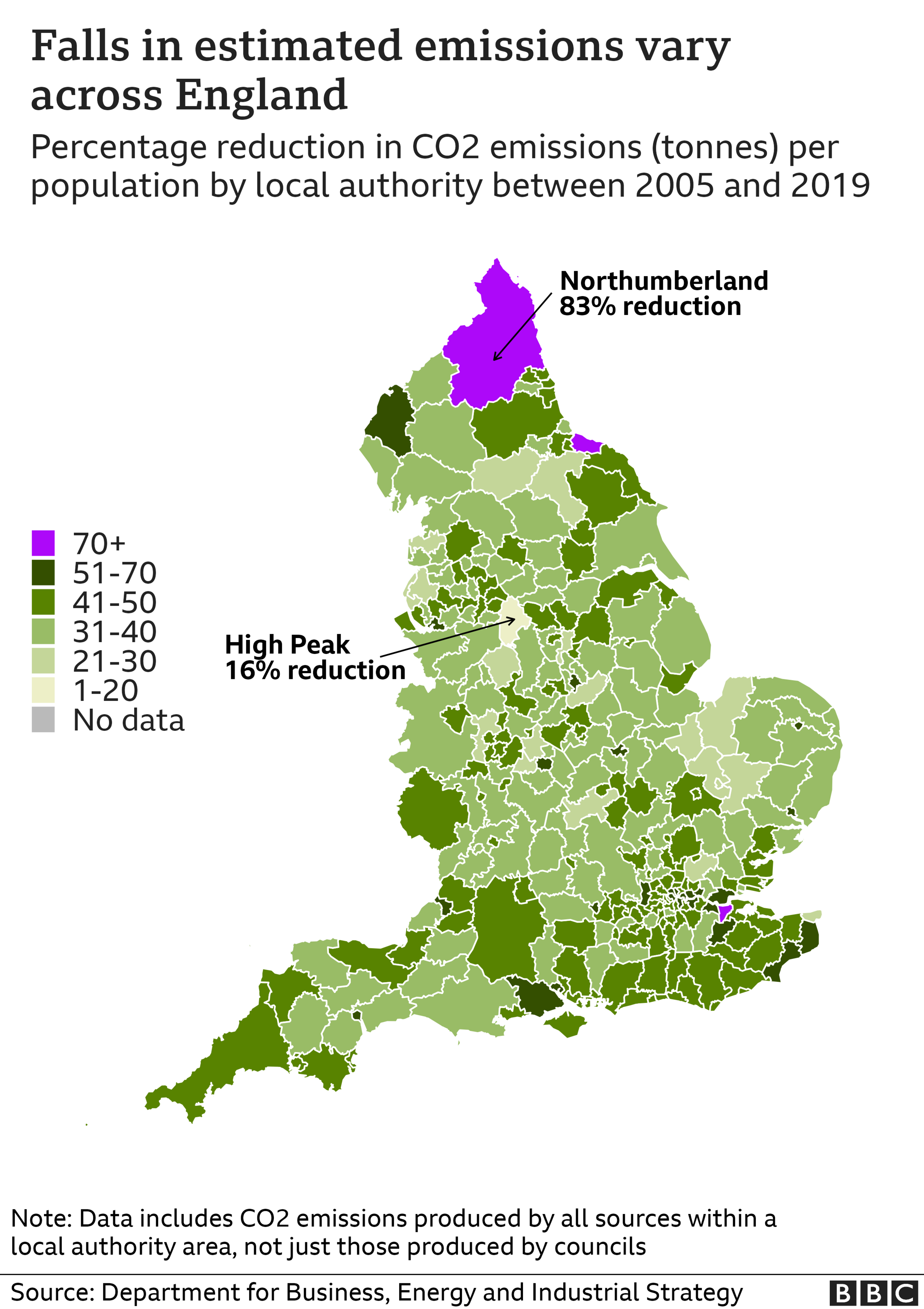

Parts of England are thought to have seen a reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by more than 80% over 15 years, official estimates show, external.

Between 2005 and 2019 Northumberland saw the biggest percentage drop in emissions per person, at 83%.

But experts say the change is not a complete picture, as industries shift overseas rather than decarbonising.

The UK has committed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 and is currently hosting COP26.

The summit, held in Glasgow, aims to bring political leaders and delegates from around the world together to make plans for tackling climate change.

Government estimates suggest the UK's CO2 emissions fell by about a third over 15 years, and all individual local authority areas saw a reduction.

This was driven mainly by changes in the fuel used to generate electricity at power stations, and the closure of industrial plants.

CO2 made up 80% of greenhouse gas emissions in the UK in 2019. These gases trap heat in the atmosphere and warm the planet.

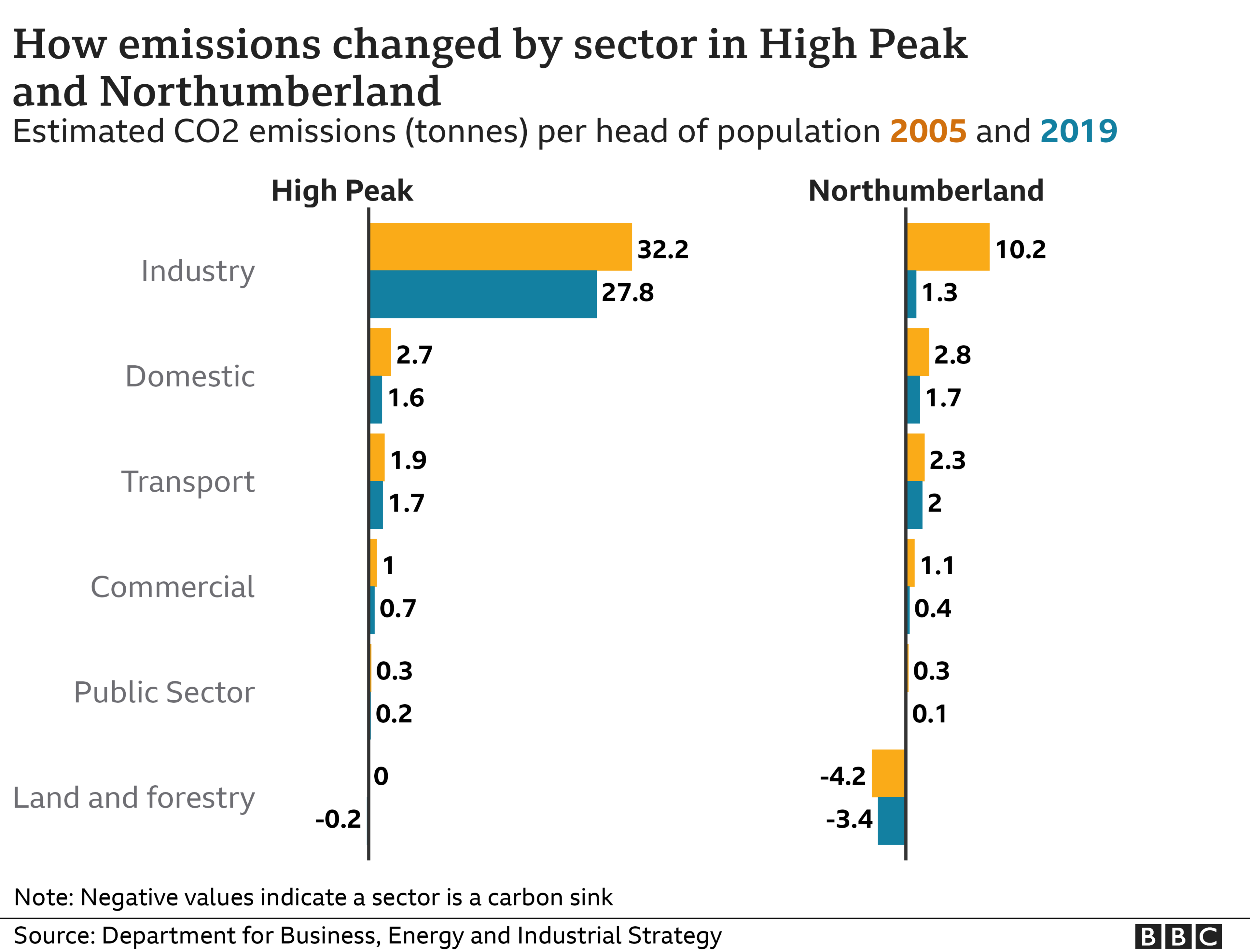

In Northumberland the drop in estimated emissions, from 12.5 tonnes of CO2 per person to 2.1, was due to the closure of industrial sites such as Lynemouth's aluminium smelting plant in 2012.

The area's forests and grassland also had a substantial impact by absorbing more CO2 from the atmosphere than releasing it, compared to other places.

Meanwhile, emissions in High Peak, which forms part of the Peak District in Derbyshire, are still dominated by industry, with only a 16% fall over 15 years.

The area is home to Hope Cement Works, a large local employer. In 2019 emissions stood at 31.9 tonnes of CO2 per person, down from 38.1 in 2005.

Cement is an ingredient in concrete, the production of which is thought to account for about 8% of CO2 emissions globally, substantially more than the aviation industry, which makes up about 2.5%.

Breedon Group, the operators of Hope Cement Works, said cement was an "essential ingredient of the infrastructure on which modern society depends" but added it recognised the carbon emissions in its products and was committed to continue to reduce these by developing "more sustainable" options.

Though experts say an overall reduction in emissions across the UK is a good sign, they also warn the loss of emissions purely in the manufacturing industry - as seen in areas like Northumberland - could be negatively affecting the UK's overall carbon footprint.

Percentage of England's overall estimated emissions in 2019

38%Transport (1.9 tons of CO2 per person)

28%Domestic (1.4 tons of CO2 per person)

21%Industry (1 ton of CO2 per person)

10%Commercial (0.5 tons of CO2 per person)

4%Public Sector (0.2 tons of CO2 per person)

Dr Jonathan Radcliffe from the University of Birmingham said the current emissions estimates "only tell part of the story" as the data measures where carbon emissions occur, and do not include the emissions attached to products bought in the UK but made elsewhere.

"Over 40% of the UK's overall carbon footprint comes from emissions associated with imported goods," he said.

"Growing the manufacturing base in the UK could reduce the UK's carbon footprint, as we progressively decarbonise, which should be recognised in how we account for emissions at a national scale, and incentives for companies to invest."

Paul Brannen, a former MEP for the North East of England who sat on the EU Parliament's Environment, Public Health and Food Safety committee, said the drop in Northumberland's emissions was the last stages of a deindustrialisation process which started in the 1970s and had a "devastating impact on communities".

He said heavy industry, and its associated hefty emissions, had "pretty much gone" from the area after a long history which began during the industrial revolution.

"What we now need to do, and have been doing, is...make use of the knowledge we've gained from our history and deploy that into new, greener technologies," he said.

In January EDF Renewables revealed plans to expand its offshore wind farm in Blyth, Northumberland

Mr Brannen said new industries such as the testing of wind turbine blades in Blyth were a good example of "building on our existing knowledge, but in a process that doesn't involve a large amount of emissions".

"It draws on the region's historic constructions skills, used to build the Tyne Bridge, and also the heavy mechanical and electrical engineering skills developed in the shipbuilding industry."

Northumberland County Council formally declared a climate emergency in 2019, alongside many other local authorities in England.

Council Leader Glen Sanderson said since heavy industry was largely dismantled the county had seen a "renaissance" of green businesses, including an electric car battery plant, an under-sea power cable project and offshore wind farms.

He added that the council sought to encourage and support skills and training initiatives needed to grow employment opportunities in green companies, and unemployment issues seen in previous decades due to the decline in manufacturing were now at a "relatively low level".

Mr Sanderson said the council intends to improve the uptake of electric vehicle charging points, launch further tree planting schemes and encourage residents to "do the best [they]can" to lower emissions in homes through insulation and heat pumps - an alternative to fossil fuel heating.

- Published15 November 2021

- Published3 May 2024

- Published29 October 2021