Amateur archaeologist helps crack Ice Age cave art code

- Published

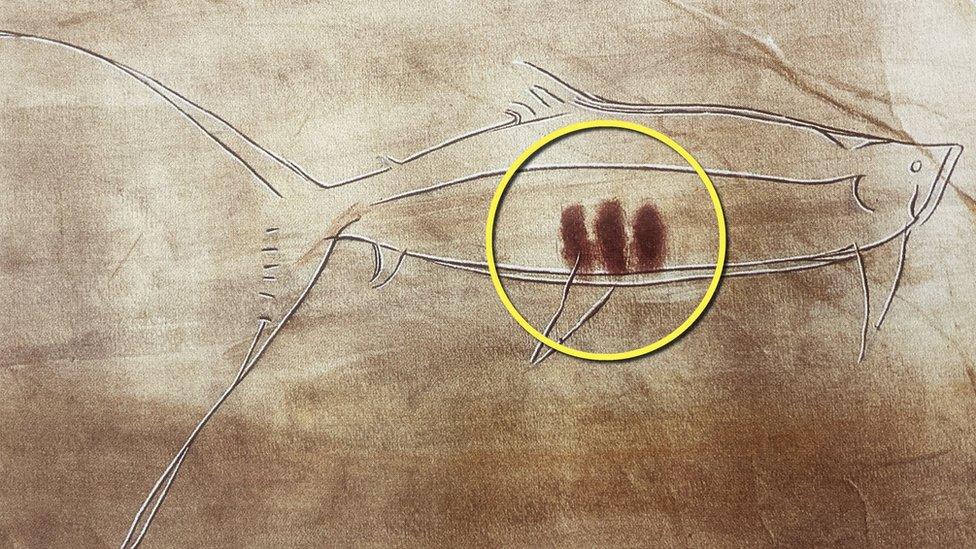

Three lines placed within an engraved salmon at Pindal cave in Spain from about 17,000 years ago

Ice Age hunter-gatherers in Europe used cave drawings to record detailed information about the lives of animals around them, a new study claims.

Markings found on paintings dating back at least 20,000 years have long been suspected as having meaning but had not been decoded until now.

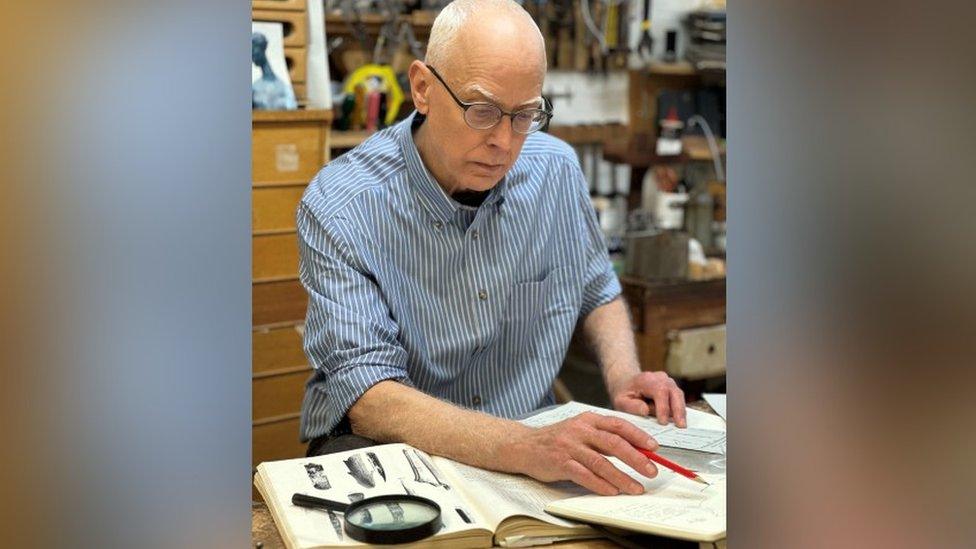

The initial discovery that the markings related to animal life-cycles was made by furniture conservator Ben Bacon.

He then teamed up with professors from two universities to write their paper.

Their findings have now been published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

Mr Bacon, from London, spent countless hours of his free time looking at examples of cave painting and analysing data to decipher what the markings signified.

He approached academics with his theory, which they encouraged him to pursue, and he went on to collaborate with two professors from Durham University and one from University College London.

Ben Bacon developed the theory that "Y-shaped" markings signified animal births

The so-called "proto-writing" system the team uncovered pre-dates others thought to have emerged during the Near Eastern Neolithic by at least 10,000 years.

The marks, found in more than 600 Ice Age images across Europe, reveal a record of information and references to a calendar, rather than recorded speech.

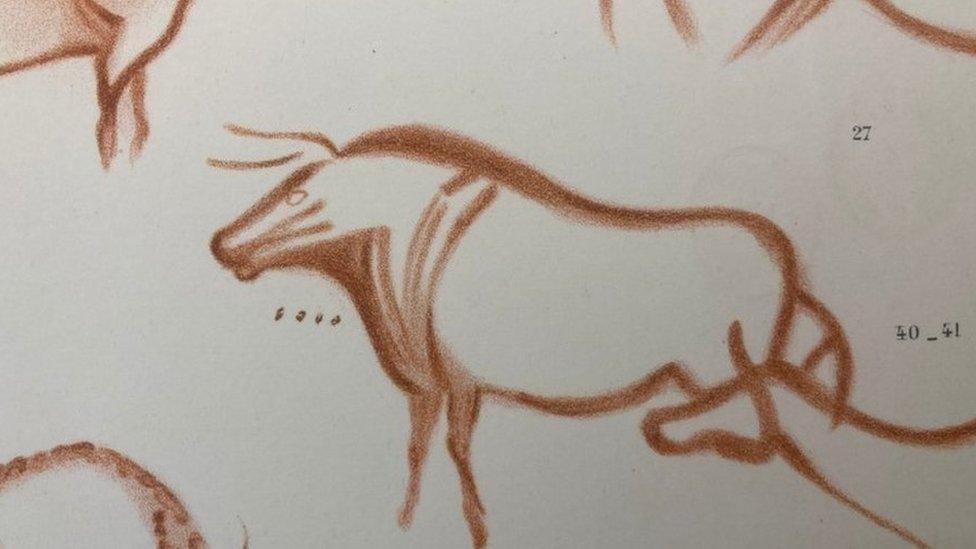

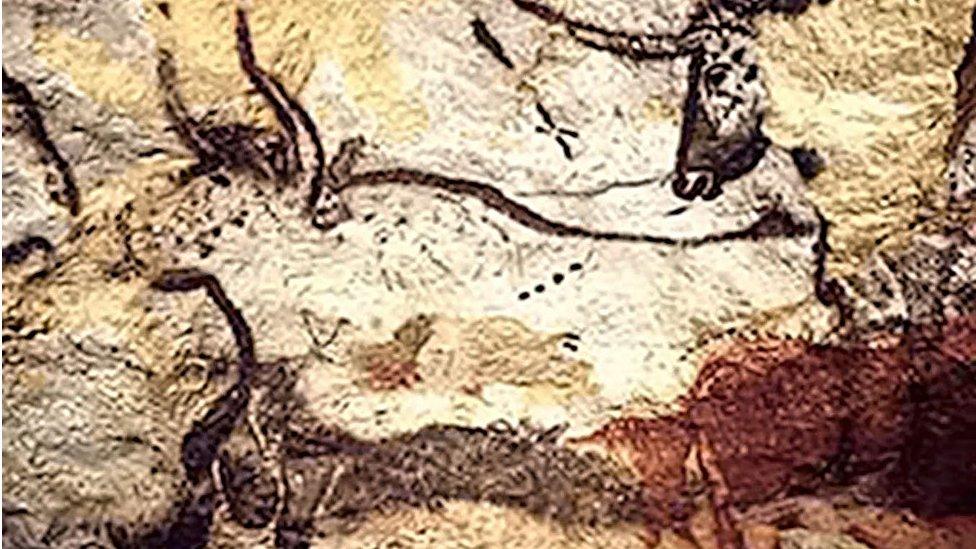

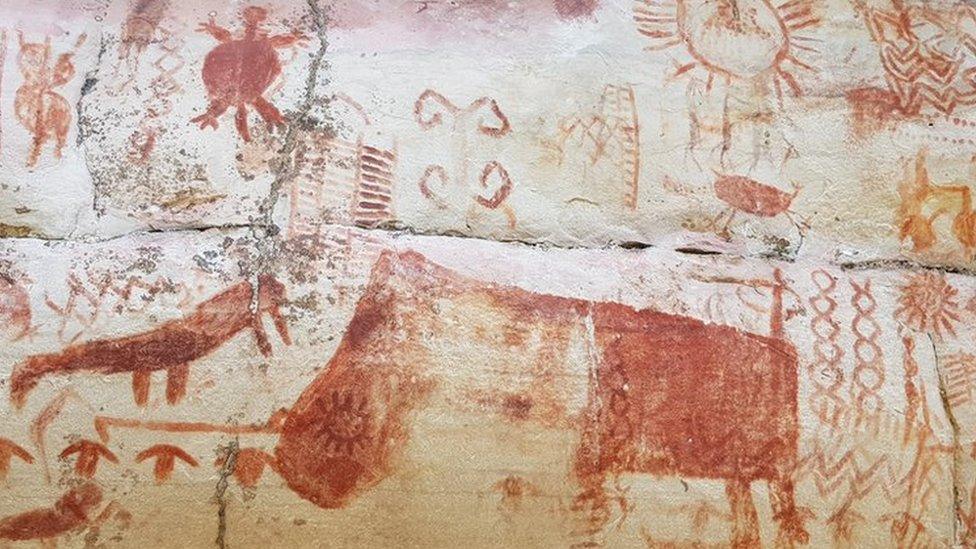

The sequences of dots, shapes and other markings appear alongside depictions of species such as reindeer, wild horses, fish, bison and extinct cattle called aurochs.

Using the birth cycles of equivalent animals today as a reference, the team worked out that the number of marks were a record, by lunar month, of when the animals were breeding.

Four dots alongside a red ochre drawing of wild cattle in La Pasiega cave, Spain, from about 23,000 years ago

Mr Bacon, who has an English degree but decided not to go into academia, said: "The meaning of the markings within these drawings has always intrigued me so I set about trying to decode them, using a similar approach that others took to understanding an early form of Greek text.

"Using information and imagery of cave art available via the British Library and on the internet, I amassed as much data as possible and began looking for repeating patterns.

"I reached out to friends and senior university academics, whose expertise was critical to proving my theory.

"It was surreal to sit in the British Library and slowly work out what people 20,000 years ago were saying but the hours of hard work were certainly worth it."

A sequence of four dots were placed within this image of a bull on the wall of the famous Lascaux cave in France about 21,500 years ago

Professors Paul Pettitt and Robert Kentridge, from Durham University, have worked together developing the field of visual palaeopsychology - the scientific investigation of the psychology that underpins the earliest development of human visual culture.

Prof Pettitt said: "The results show that Ice Age hunter-gatherers were the first to use a systematic calendar and marks to record information about major ecological events within that calendar."

Prof Kentridge added: "The implications are that Ice Age hunter-gatherers didn't simply live in their present, but recorded memories of the time when past events had occurred and used these to anticipate when similar events would occur in the future, an ability that memory researchers call mental time-travel."

Among the researchers was Tony Freeth, honorary professor at University College London, who said: "I was stunned when Ben came to me with his underlying idea that the numbers of spots or lines on the animals represented the lunar month of key events in the animals' life-cycles."

The team, which also included independent researchers Dr Azadeh Khatiri, and retired history teacher Clive James Palmer hope to do more.

Mr Bacon said: "As we probe deeper, what we are discovering is that these ancient ancestors are a lot more like us than we previously thought - these people, separated from us by many millennia, are suddenly a lot closer."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published3 December 2020

- Published19 October 2016

- Published2 May 2016