Should children watch toy unboxing videos?

- Published

Ava's most popular video, which has been viewed 8.6m times, shows her unboxing a toy Barbie house from Argos

Children around the world are currently trying to decide which toys to put on their Christmas list. Some browse catalogues for inspiration or look in toy shops and watch TV adverts, while others are turning to toy unboxing videos to make up their minds. What is the appeal of these videos, and are they in any way harmful?

For nine-year-old Verity, the unboxing videos have been a great way to work out which toys she really wants this Christmas. In these videos, children, or in some cases just a pair of hands, take toys out of their packaging and play with them.

Verity particularly likes watching Shopkins, Lego and Harry Potter toys being opened on YouTube, which is the main platform for this type of content. "It gives you more information than just seeing an advert. It's more interesting because these videos give you more details about how something works and then they show you how it works."

Verity, who lives in St Albans in Hertfordshire, also likes to make her own videos, but only for family and friends to watch. "I don't want everybody to see them because they might make fun of them and make bad comments," she says. "People can be mean."

Verity likes watching toy unboxing videos to narrow down her Christmas list

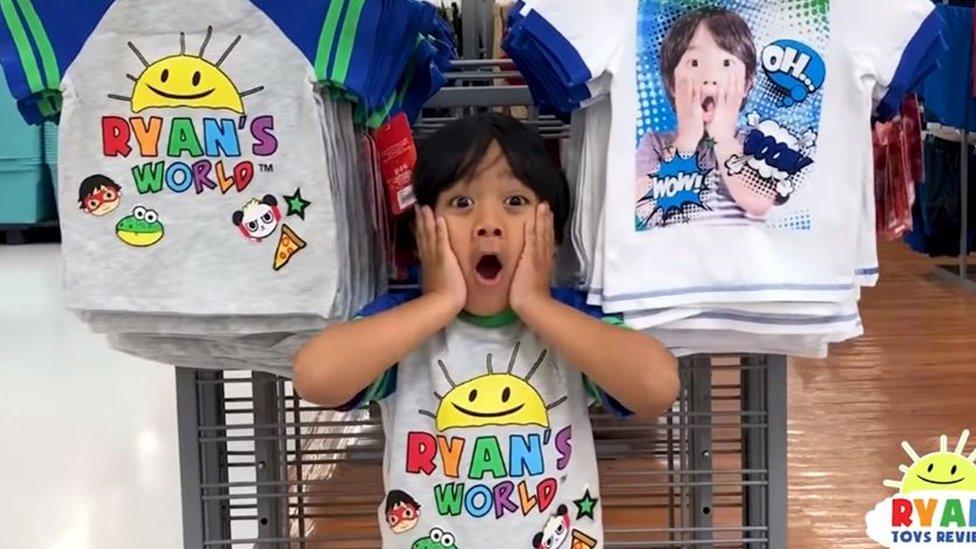

Ryan Kaji was among the first children to start making these videos in the US in 2015, when he was four years old. An early clip, external, in which he opened up a giant egg with more than 100 items inside, has been viewed more than a billion times. Ryan was the highest paid YouTube star of last year, when he earned more than £17m, mainly through partnerships with toy firms and his own TV show.

Eight-year-old Ava, who lives near Leicester, is hoping to emulate his success. She started her YouTube channel Ava's Toy Show when she was three. A video showing her unboxing and playing with a Barbie house, external has had more than 8.6 million views.

Her mother Lynsey Brown, 36, says Ava has always been a performer and loves filming the videos.

Ryan Kaji, who was the highest paid YouTube star of last year, has had nearly a billion views for this video

"Ava decides which toys to play with and we feel like she is learning a lot from watching her dad edit the videos. Children can relate to her because she's very down to earth."

Ava donates all of the toys to local charities, including a special needs school, and is "very aware" many of her followers, lots of whom live in the Philippines. are not as fortunate as her.

"As a parent, it is so frustrating when you spend a fortune on a toy that turns out to be rubbish, so hopefully we can help people decide what presents are actually worth buying this Christmas," she says.

Cambridge University research associate Dave Neale, who studies early-years play, believes these videos can have a positive impact if they encourage children to play with toys, and explore them more deeply.

"Playing is a vital part of early development, it teaches us language skills and emotional regulation, how to share, and the interaction is a bonding experience, so anything that encourages play is essentially a good thing," he says.

However, he is concerned about the lack of interaction and socialising involved. "When children play with toys they are problem-solving and being creative, figuring out how the toy works, or what other things they can do with the toy and that becomes a reward. Watching these videos just gives them the last bit without the other parts. It is a more shallow engagement."

Emma Connell-Smith has banned her children from watching YouTube unboxing videos

Mother-of-three Emma Connell-Smith, from Tattingstone in Suffolk, does not like the effect these videos have on her seven-year-old twin boys Oliver and Thomas.

"The toys are very expensive and it makes children feel inadequate if they can't have them all," she says. "I also don't like the fact that these videos are so long and children seem unable to tear themselves away."

Her three-year-old daughter Tilly has also asked to watch them, but Mrs Connell-Smith has decided not to let her. "The toy videos aimed at younger children often use baby language, and the toddler when watching this repeats this language, often forgetting how to use the actual words they have."

A video showing a small boy dressed as Spiderman unwrapping and assembling a toy car has been viewed 276 million times on YouTube

This video, called Play Doh Ice cream cupcakes playset playdough by Unboxingsurpriseegg, has been viewed 879 million times

Emma Worrollo, who has two children and writes about child culture and play, external, believes this type of content can be addictive, and says the trend is showing no signs of slowing down.

"It is capturing the eyeballs of kids around the world who are drawn in by the surprise-and-reveal format," she says. "This content has no narrative, no characters and no ending, which means it is hard for a young child to switch off or engage with it in a meaningful way. The experience is hypnotic and many parents report a negative impact on behaviour when young children view this type of content."

Emma Worrollo limits the amount of time her children Phoenix and Indy spend on YouTube

In Brazil, where advertising to children is illegal, the public prosecutor's office has filed a lawsuit against YouTube in regard to these videos, accusing the firm of "engaging in abusive advertising practices toward children".

In the US, Ryan Kaji, who is now aged eight, was the subject of a recent complaint filed by a watchdog group, external with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), alleging he was manipulating children who were too young to distinguish between an advert and a review.

Google, which owns YouTube, has recently created a new system, external in which content directed at children must clearly labelled, so the site can turn off targeted adverts. It comes off the back of a settlement with the FTC for violating children's privacy.

Ryan Kaji has made millions from toy unboxing

Here in the UK, a spokesperson for YouTube said it took quick action against any videos that do not declare a paid-for promotion, and videos that do declare this are not available on the YouTube Kids app. However, it has no rules about toys being given to children in exchange for being featured in videos.

While toy unboxing videos continue to rack up millions of views, parents need to make up their own minds whether they are a brilliant way of narrowing down that Christmas list or a tool for manipulating their children.

- Published23 August 2019

- Published4 September 2019

- Published3 September 2015