St Albans Cathedral: How were the remains of Abbot John reburied?

- Published

A facial reconstruction of Abbot John was revealed in 2020 based upon his skull, which the cathedral said had been preserved well enough for this work to be carried out

When the remains of a 15th Century abbot were carried to their final resting place in St Albans Cathedral on Saturday, five years after he was found in an unmarked grave, it begged the question, how exactly do you recommit the body of a Benedictine Abbot some 600 years after his death?

It was during the building of the cathedral's new welcome centre in 2017 that an unearthed skeleton was later found to be that of Abbot John of Wheathampstead.

Called to lead the church twice - from 1420 to 1440 and then from 1451 to his death in 1465 - he physically restored the Abbey after the Black Death with a programme of building and, as the English representative of the clergy at international conferences, also gained back its reputation.

In short, he was a mover and shaker in the Norman cathedral's history - but his burial site remained a mystery for centuries until a team of archaeologists from the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, external found him, and so began the journey to return him to his church.

The remains of Abbot John were found during work to create the cathedral's new welcome centre

In order to excavate Sumpter Yard, where the new centre now stands, the cathedral had to get permission.

That permission involved both acquiring a licence to exhume any human remains and ensuring that those remains are reburied with a suitable service.

Five years on, after scientific analysis - and a pandemic - the abbot was once again laid to rest, this time near the Shrine of St Alban during a special evensong.

Organising the reburial involved expert help from historians, a funeral director and even a plumber.

Project manager and cathedral guide Julia Low said: "We had to write the rule book, there's no manual that says how do you bury an Abbot.

"And we couldn't put him back where he was found because there is now a new building on it. So we had a problem."

Where?

Abbot John's ossuary lies in an open vault - on view to the public - next to the mortal remains of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother of Henry V

Eleven abbots and three monks found during the building of the Chapter House in the 1980s were all buried in the presbytery so there was "no room for him in there", Ms Low explained.

So it was decided to lay him with his friend and colleague, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester - brother of King Henry V, who died in 1447 and the only royal to be buried at the cathedral - in a small memorial chapel beneath another chapel which contains the shrine of St Alban, Britain's first saint, who was buried on the site 1,700 years ago.

As an open vault, as long as they did not touch the fabric of the building - for example by putting up a shelf - formal permission was not needed, but the Chapter was consulted for their agreement and the Fabric Advisory Committee was also advised as a courtesy, Ms Low said.

In addition, as the vault contains the mortal remains of a former Duke of Gloucester, the project team advised the current Duke of Gloucester.

Ms Low added: "The obvious place to put [Abbot John] was with his friend in the vault in the Chantry Chapel.

"But there was not a lot of room in there for a coffin either so we had to think outside the box, if you'll pardon the pun."

How?

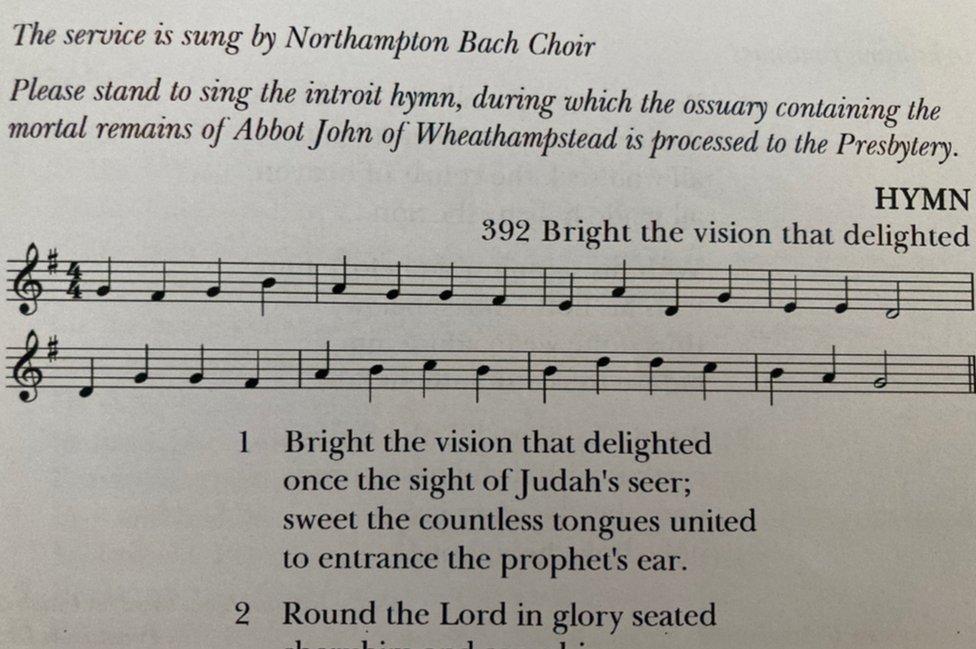

Abbot John's ossuary was carried to the presbytery in the cathedral during a special evensong service attended by hundred, including some of the team who found him

As space was limited, Ms Low said it was decided they needed to use an ossuary - a bone box - instead of a coffin.

"This isn't normal practice in the Church of England or the UK - it's a much more European practice, so we wondered where could we get one?" she said.

"There had been a huge find of bones in Bamburgh, external and they happened to have a spare box which they said we could have."

She said the zinc box is 20in (50.8cm) long, 17in (43.1cm) high and 8in (20.3cm) wide and has a cross on it.

In a ceremony on the Monday before the reburial, Ms Low witnessed the Dean of St Albans, the Very Reverend Jo Kelly-Moore, place the Abbot's bones in the ossuary and recorded the moment for the archive.

"It was amazing to see her and her predecessor together like that," she said.

What was he interred with?

Dean of St Albans, the Very Reverend Jo Kelly-Moore, censes the ossuary before its commital

"We knew what to put him in and where to put him - but we didn't know if there was a Benedictine format for burial," Ms Low explained.

So she contacted Jason Downing at local funeral directors Philips

"He consulted the Abbot of Ealing - which is a Benedictine house [in west London] - who said there was no special formation required for the bones but he needed to be buried with certain things, a pectoral cross, his crosier (a staff), a chalice and a patten dish," said Ms Low.

But there had been nothing found with the skeleton except for three papal bulls given to him by Pope Martin V, confirming the papal privileges he gained in 1423 and which ultimately provided the key to his identity.

With limited room in the box, the team assembled some items - a pewter pectoral cross, replicas of the papal bulls - the real ones are on display - and a vellum scroll which they had made that names him, what he was buried with and all the people on the working party who exhumed and reburied him.

The ossuary is covered by a pall hand-embroidered by experts at the Royal School of Needlework which depicts his crest - an eagle and a lamb

The ossuary is covered by a pall (the cloth normally used to cover a coffin during funerals) which Ms Low had hand-embroidered by experts at the Royal School of Needlework which depicts his crest - an eagle and a lamb.

"It's a fabulous piece of work," Ms Low said.

Finally the box was sealed shut by plumber Jake Pritchard which "has fascinated everyone", she added.

"It is a specialized job, because zinc and the lead solder heat at different temperatures so there is the distinct possibility of damaging the box," she said.

"Jake did a beautiful job creating a really smooth seal that will not rub against the material of the pall, causing wear on the cloth."

When?

The ossuary is lowered into the Chantry Chapel beneath St Albans' shrine, a part of the cathedral which continues to be a place of pilgrimage

The ossuary was lowered into the vault by straps during a service on 30 July and is now on public view.

The date marked 602 years to the day since the Abbey received permission from the King to elect a new Abbot, which turned out to be John.

It was first hoped it would take place on the 600th anniversary in 2020 but the Covid-19 pandemic put paid to that.

Julia Low said the cathedral now has a "blueprint for burying an Abbot".

Ms Low said she was beginning to get "a bit agitated".

"He'd been out of the ground for five years, he had to go back," she said, "five years on a shelf is not fun for anyone."

"It's taken longer than we expected, but in the end it was absolutely to the day, that's the hair raising bit - it was meant to be."

The aftermath

Julia Low hands the Dean the Abbot's ossuary as he is walked "one final time through the Abbots door"

It has been a mammoth effort to return Abbot John to his church and one Ms Low would not change.

"As an historian, I thought it was great we'd found John and it was important to me," she said.

"But it was only when I had arranged for his remains to be brought back from Canterbury and the boxes were put in my arms that I got an immediate connection as I walked him back into his Abbey.

"It's been amazing to project manage, I wouldn't begrudge a minute of it, to be part of history, to have our names on that scroll, it's just staggering.

"The final lowering into the vault with such precision and dignity did find a tear on my cheek... It's so good to know that he is where he belongs, safe in the Abbey he so loved and I played a small part in his history.

"I'm not moving him again."

Three papal bulls - a type of public charter issued by a pontiff - issued to the Abbot by Pope Martin V were found with his remains - replicas have been placed in his ossuary

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published1 August 2022

- Published27 July 2022

- Published7 September 2020

- Published22 June 2019

- Published7 December 2017