Former Kuwait hostage says she did not expect to survive captivity

- Published

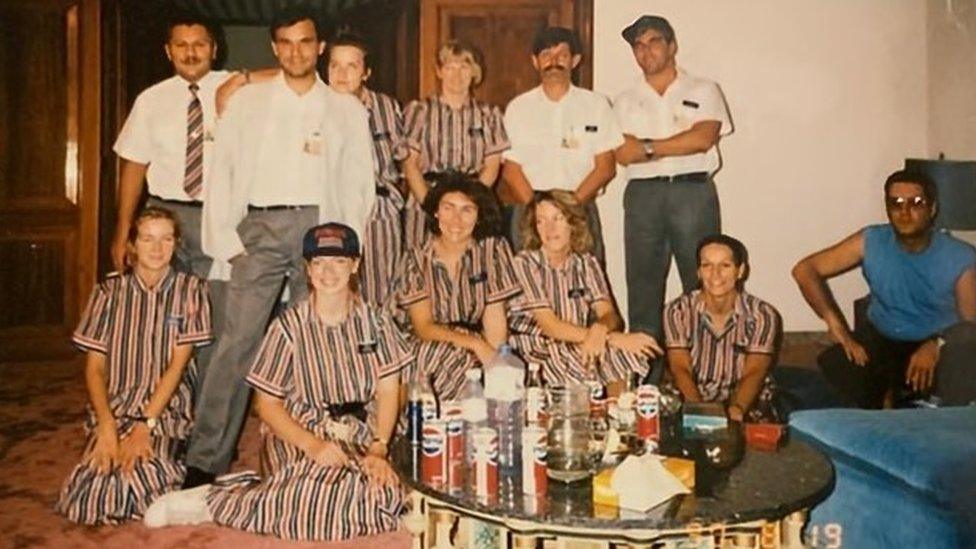

Bryony Reynolds was one of more than 300 people detained by Iraqi troops and used by Saddam Hussein as "human shields"

When Iraq invaded neighbouring Kuwait on 2 August 1990 hundreds of foreign nationals were detained and used as "human shields". As former hostages prepare to take legal action against the British government and British Airways, one - a former cabin crew member - reveals what it was like to be caught up in an international stand-off.

Bryony Reynolds was a 24-year-old cabin crew worker when she flew into Kuwait City from Delhi on 1 August.

She expected to fly back to London the following day.

During the early hours of 2 August a second British Airways (BA) flight - BA149 - landed in Kuwait to refuel.

Ms Reynolds, now 58 and living near Harlington in Bedfordshire, awoke at the Regency Palace Hotel to find a note pushed under her door.

Kuwait, the note said, had been invaded.

After the crew and passengers disembarked, flight BA149 aircraft was destroyed on the runway

She found the hotel lobby "absolutely packed" with armed Iraqi soldiers.

"That's when I realised we were in serious trouble," she said.

She and her airline colleagues tried to call their families but the telephone lines had been cut.

They were later joined by the passengers and crew of flight BA149, which had been destroyed by Iraqis once it had been vacated.

For the next three weeks they were holed up at the hotel, which the Iraqi military used as a base.

Bryony Reynolds [in the baseball cap] said she was "bizarrely smiling" in a picture taken with other hostages at a Kuwait hotel - it's a "natural reflex when someone points a camera at you"

On 18 August, the hostages had their passports removed and were herded onto buses and taken to the hospital university in Kuwait.

"I was absolutely petrified," Ms Reynolds said.

"Your only thoughts are from history when people got separated, like in World War Two, so I thought 'no way is this a good thing'."

At the university, they were split into groups of 12 which were taken away one at a time.

"We thought 12 was a nice, tidy number for a firing squad," she said. "So when it was our turn my heart was beating like crazy."

Instead they were taken to a "disgusting" house and put in one room with faeces all over the walls and yoga mats to sleep on, she said.

On the first night, Ms Reynolds' group was taken to a dining room where they were offered a meal of "a sheep's head with the eyes still in it, in a kind of greasy, grey broth".

"If I'd known it was the best food we'd have," she said. "I'd probably have tried to eat a bit more."

The next day they were moved to the summer palace of the Kuwaiti royal family, which was "not as grand as you would think".

They were only twice allowed outside for exercise and were made to watch speeches by Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein on television.

"We didn't expect to survive," Ms Reynolds said. "It was a question of when are they going to shoot us, we didn't expect to get out alive."

When the women and children were freed, Ms Reynolds felt a great sense of guilt.

It was nearly Christmas when the final hostages returned to the UK

The route to freedom included a 17-hour journey through the desert in 40C (104F) heat to Baghdad.

"At one point we stopped just outside Basra," she said. "They [the soldiers] marched us off the coach towards a big dug out pit in the desert and I thought this is it, they are going to shoot us.

"Then they just laughed and got us all back on the bus.

"They loved teasing us like that."

They were taken to a hotel in Iraq where the hostages were told they would "only be going home if they were given their passport".

On the day of her 25th birthday, Ms Reynolds was handed her passport.

She arrived at Heathrow on 2 September. Her male colleagues would not be home until December.

Ms Reynolds said meeting up with other former hostages after three decades had "really helped her"

She claims she was "pestered" back to work by BA.

"BA phoned me every day," she said. "They said it was a 'care call' and told me I could have as much time off as I needed but at the same time asked me when I might come back."

She was initially put on "buddy rosters", in which you were meant to be on the same flights as a trusted colleague.

But this did not last, according to Ms Reynolds, who claimed she was told "the other girls [on the rosters] were fed up with me" and she was kept away from her fellow former hostages.

"We were all [essentially] kept apart from each other for so many years, being told we were the only ones who were suffering and everyone else was coping.

"We now know that this was not true," she said.

"We have all realised we had not only had a shared experience in Kuwait but a shared experience since we got back as well."

Iraqi forces abandoned vehicles as they retreated from Kuwait

She was privately diagnosed with PTSD about six months after her return to the UK.

But it was not until 1997 - having struggled to cope for many years - that she was medically retired.

"I thought I was mad for 30 years, I don't want anybody else out there feeling this way," she said.

Ms Reynolds is one of the former hostages involved in a claim expected to be brought before High Court in London in the next few months.

The group's legal firm, McCue Jury and Partners, said "evidence exists" that the government and BA "knew the invasion had already begun" when they allowed the plane to land because it was being used to insert a team into Kuwait "for a special military operation".

A BA spokesman said: "Our hearts go out to all those caught up in this shocking act of war just over 30 years ago, and who had to endure a truly horrendous experience.

"UK government records released in 2021 confirmed British Airways was not warned about the invasion."

It declined to comment on Ms Reynolds' claims about her subsequent treatment by the airline.

A government spokesman said: "The responsibility for these events and the mistreatment of those passengers and crew lies entirely with the government of Iraq at the time."

After leaving BA, Ms Reynolds trained to be an actor and now runs a small theatre company in Toddington.

But the terror of Kuwait has a long tail.

"It's always there," she said. "Every time I go to sleep I'm still dreaming of Kuwait, a part of my mind is still there, it just doesn't go."

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published12 September 2023

- Published11 December 2020

- Published18 January 2016

- Published17 January 2016