Was my dad a killer? The diary that left writer Saul Wordsworth wondering

- Published

Saul Wordsworth set out to discover the truth about his late father Christopher in his podcast series Devil in the Wilderness

Saul Wordsworth remembers when he first realised his father Christopher may have taken a terrible secret to his grave.

He knew all about his quick temper and explosive outbursts of rage, but a set of his diaries inherited by Saul hinted at something altogether darker.

"I think he might have killed somebody," is what Saul, a writer, remembers being told by the woman transcribing them.

The passage she highlighted referred to hiding a body until a search party had gone.

A smoking gun? Saul was not convinced. To him, it appeared fictional.

Growing up in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, he knew his father as a teller of tall tales whose own back story was shrouded in mystery.

An acclaimed literary critic and sports writer for The Observer and The Guardian, Christopher was also a frustrated novelist whose lifelong ambition tantalised, tortured and ultimately eluded him.

Hints at a decades-old dark secret, therefore, did not seem fanciful to Saul, but were definitely intriguing.

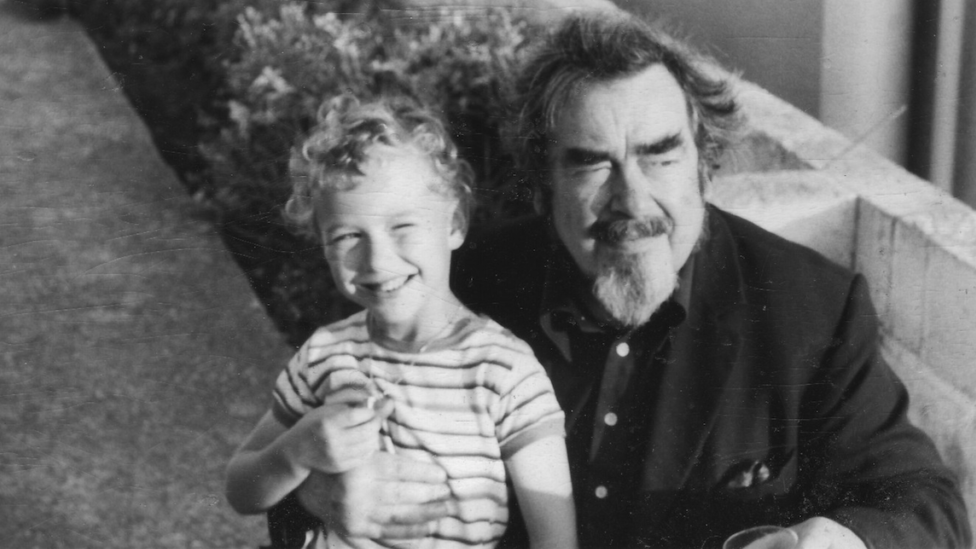

Saul, a writer, was the only child of his father's third marriage

There were other potentially incriminating lines. One read: "It is that element of calculation in it that shames me and makes it murder."

Saul, 51, reasoned that had his father really murdered somebody, he would not have risked writing it down. But could he have killed someone unintentionally?

Armed with the diaries, Saul, who lives in north London, began disentangling fact from fiction for a six-part podcast series, Devil in the Wilderness, external, for which he also composed the soundtrack.

Tracking down elderly friends, relatives and former colleagues of his father, he built a picture of a brilliant but troubled man with a chaotic and disturbing past.

"I hope you come out of the podcast all right, Dad, but either way, forgive me," he says, in the first episode.

Growing up in Harpenden, Saul found his father's frequent angry outbursts terrifying

Born in Kolkata in 1914, Christopher drifted for decades before entering journalism aged 50.

His flair for words saw him dubbed "Fleet Street's prince of phrase-makers", credited by some with coining the famous saying "legend in his own lunchtime", external.

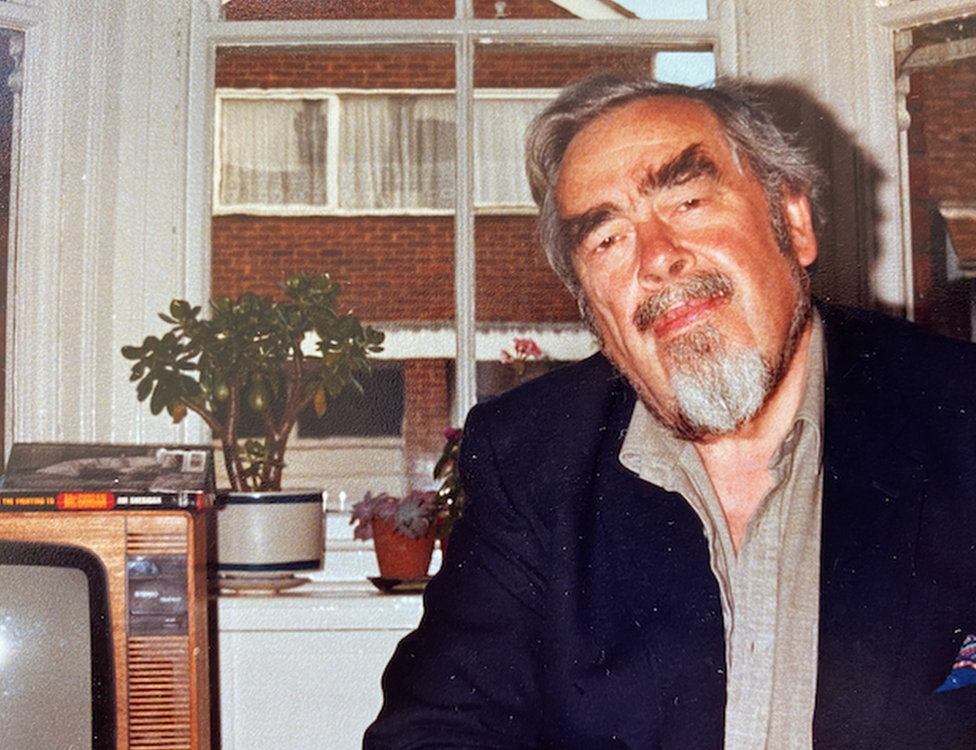

He died in 1998, aged 83, in his favourite chair, a review copy of a book beside him.

His own long-promised novel remained unwritten.

Saul was the only child of his father's third and final marriage, to fellow Observer book critic Tamara Salaman

Christopher was 57 when Saul, the only child of his third marriage, was born.

The pair's relationship was often fractious. Sometimes kind and very funny, Christopher was also prone to terrifying anger.

"Everything was turned up to 11," says Saul.

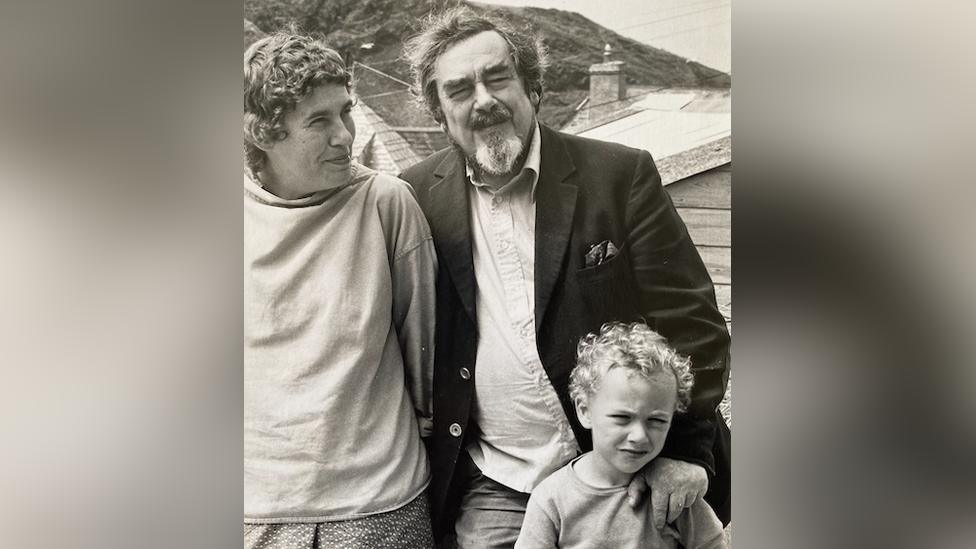

He also became a vessel for his father's thwarted ambitions. "Saul, I live through you," he would often tell him.

Later, when his own mental health suffered, Saul realised the burden this had been.

Christopher died in 1998, when Saul was 25

The pair bonded over a shared love of sport, but Christopher remained enigmatic.

"He was a bit of a fabricator of lots of things, not least his own life," says Saul.

"There was something about him that was mysterious and unknowable, and he liked it that way."

His father's tall stories included the bizarre claim that Hitler was still alive.

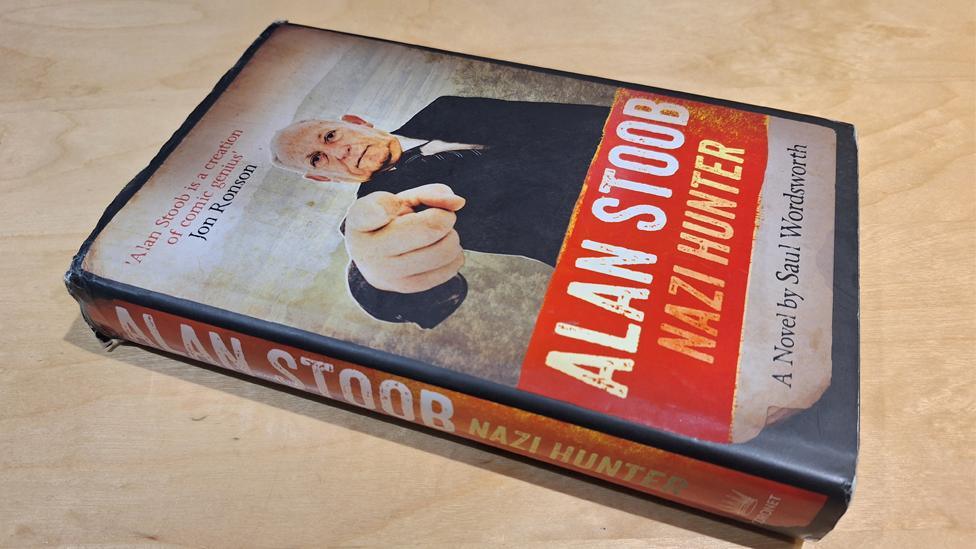

This unnerved Saul but ultimately inspired his comic novel Alan Stoob: Nazi Hunter.

In seeing it published, Saul achieved something his father never managed.

Saul said his father saw him a vessel for his own thwarted ambitions, telling him "Saul, I live through you"

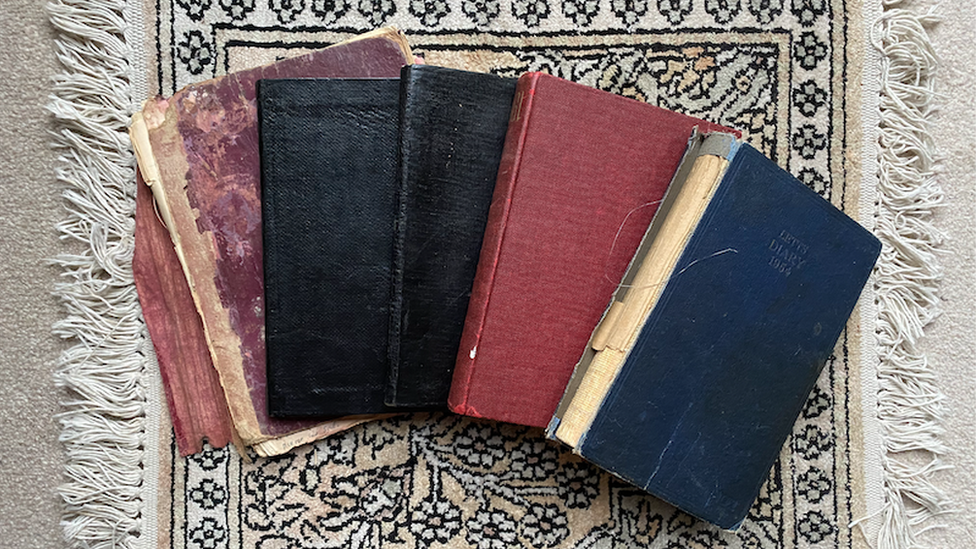

Christopher's diaries date from 1953 to 1963, when he was divorced, penniless and living on trout and potatoes in a remote cottage in the wilds of north Wales, suffering writers' block.

Saul had known of the diaries for years but had never seen them, imagining them "distantly glowing" in a trunk in his father's study.

When they finally came his way, carefully wrapped in polythene, Saul sensed they were "precious cargo".

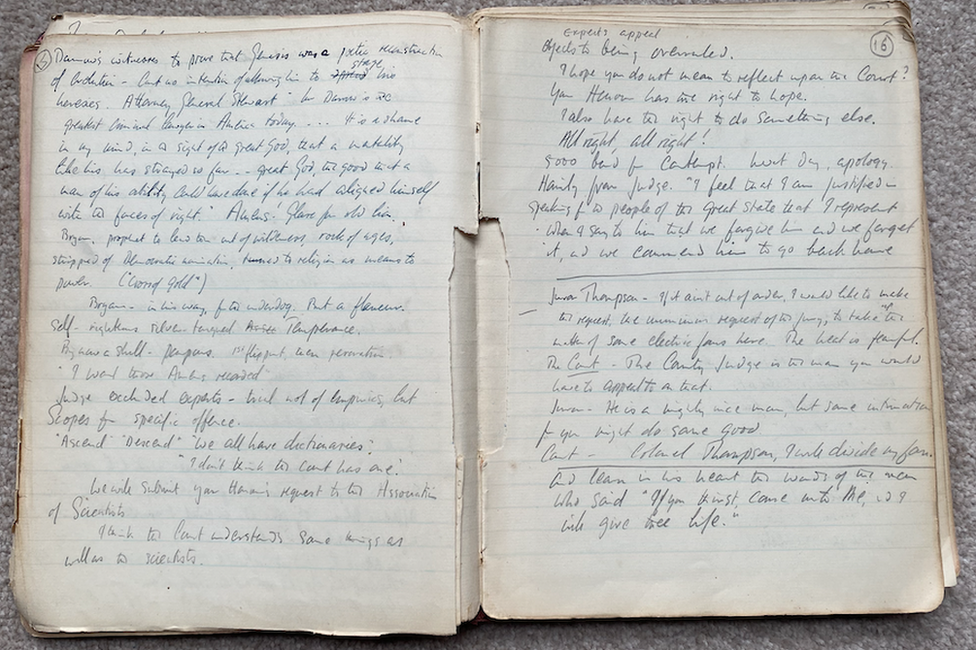

Each time he tried to read them, though, he was defeated by his father's handwriting, so he recruited a transcriber called Emma to help.

Saul's comic character Alan Stoob and his 2014 novel were partly inspired by a tall tale his father told

Opening the first of five battered volumes, she inhaled its musty aroma, telling Saul: "I can do this. If you're happy with the first one, I'll transcribe the other four for you."

A week later, a full transcript of the first diary, dated 1953, arrived.

Christopher's words reveal a man at a low ebb. "I have arrived in my late 30s as nearly naked as is possible for a man to be, in the practical worldly sense," he writes.

"Money, shelter, reputation, friends, relatives, useful acquaintances, achievements, I have none. It would have been impossible to have devised a more complete downfall in fiction."

Christopher Wordsworth's diaries are contained in five hardback volumes

His father's handwriting proved difficult to read, prompting Saul to have the diaries professionally transcribed

Over the next six weeks, four more documents arrived, totalling nearly 60,000 words.

"I wasn't shocked by the quality of the writing, but I was blown away by the sheer weight of purple prose, and just the shimmering wondrousness of my dad's ability with the written word," says Saul.

"But all the while he's lacerating and battering himself about not being able to write, because, for him, writing only meant writing the novel."

Ty Cipar, the cottage where Christopher lived alone in the late 1950s, stands in a remote spot in the Migneint, a bleak area of moorland in Eryri (Snowdonia)

Saul learned that, aged three, his father was left with a relative in Oswestry, Shropshire, while his parents returned to India.

Later came boarding school and an abortive spell at Oxford University.

Christopher also burned through a large inheritance and was reduced to begging from friends and family.

The diaries reveal Christopher's affairs, including a five-year relationship with Sue Russell, daughter-in-law of mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell

He even tried to sell his sister's house from under her while she was on holiday, before throwing himself on the mercy of friends in Wales.

His diaries are packed with secrets, including affairs with friends' wives and hints at further children.

They detail a tempestuous and ultimately doomed five-year relationship with Sue Russell, daughter-in-law of philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell.

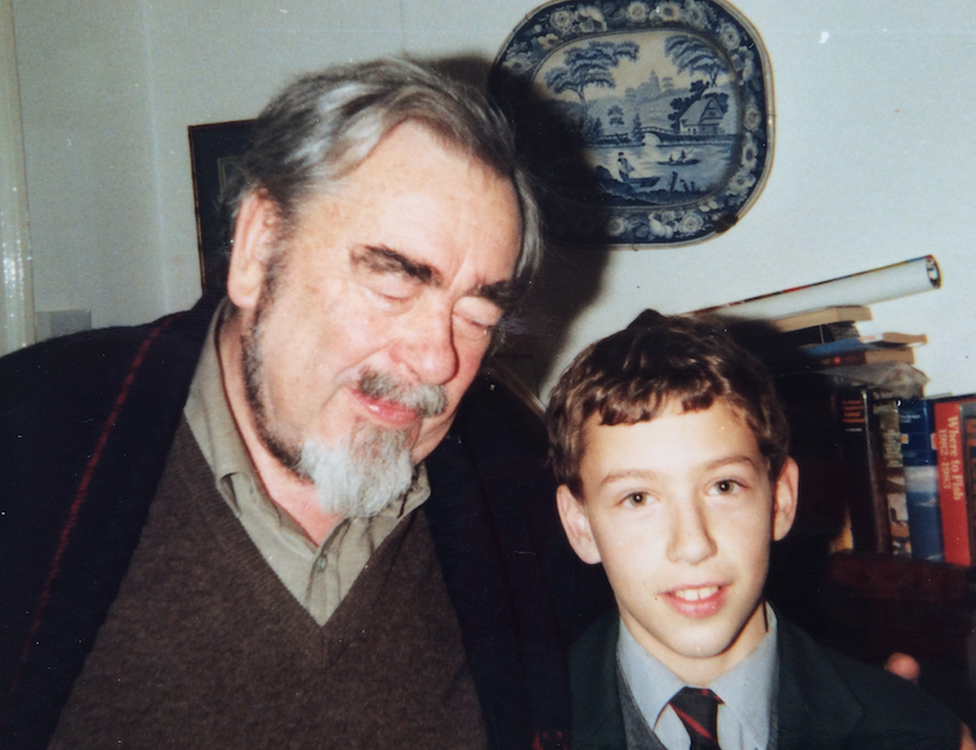

Christopher, pictured with first wife Joan and daughter Diana, served in the Indian Army during World War Two

Saul says his father's behaviour was often "quite sociopathic" and "selfish and obviously damaged and wounded and desperate".

He found himself returning to another sentence in the diaries, that read: "More than any other in my life, I have been the prisoner of two events: striking a pregnant Joan, and that moment in Iraq."

What did it mean? The first part, sadly, was obvious enough - an admission he had beaten his first wife - but the second, less so.

Could Christopher have killed someone while serving with the Indian Army during World War Two?

"There is no exploration of what that moment in Iraq is, and I think it's deliberate," says Saul.

"He doesn't talk about the incident or the moment because he's fearful... that if he does record it, and somehow someone comes across the diaries, he would be answerable."

Saul travelled to Wales during his research for the podcast

Saul trawled through Indian Army records and quizzed his father's remaining friends.

Eleanor Brooks, by then in her mid-90s, told him: "I wondered if he was actually afraid of something catching up with him."

Saul also thought back to childhood when he often found his father sitting, head in hands, in a dark mood.

"He would talk about a misspent youth. He would talk about the years that the locusts had eaten... but also [there was] a sense that this is a man with a heavy weight on his conscience."

Saul interviewed friends of his late father, including Eleanor Brooks (far right), for the podcast

Saul also considered his father may have killed someone in a road accident while drunk.

Podcast listeners will hear Saul reach his own conclusions. But questions remain, and he plans further research.

Despite the heavy subject matter, Saul says making the podcast was a fulfilling and "tremendously joyous experience".

And although many of its revelations reflect badly on his father, Saul does not entirely condemn him.

Saul believes his father would be pleased at being the subject of a podcast

"I think that he indulged in some monstrous behaviour without ever quite being a monster himself, but more like the walking wounded," he says.

"I have tremendous compassion for anyone who suffered at his hands."

These include Saul's half-siblings, whose "neglect" through Christopher's absence and lack of support he finds "close to unforgiveable".

What would Christopher's reaction to the project have been? "Who wouldn't be pleased with their own podcast, 25 years after they've died?" says Saul.

Has it brought him closer to his father? "He's closer and yet he's far away as ever," Saul says.

"Ultimately, we're all unknowable. But there were few more unknowable than my dad."

You can hear more about this story on Justin Dealey's show on BBC Three Counties Radio from 10:00 GMT on Sunday 24 March.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk , externalor WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published28 December 2023

- Published4 January 2015