DNA breakthrough ends wait to catch Yolande Waddington killer

- Published

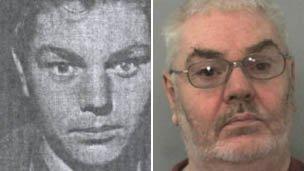

How Burgess looked in the late 60s (left) compared to the present day

For 46 years the family of murdered Yolande Waddington doubted they would ever get justice for their daughter.

No-one was ever charged with her brutal killing and the case went cold.

In the subsequent years, the 17-year-old's mother passed away but her remaining family has lived to see the day her killer David Burgess was convicted.

Burgess is already serving a life sentence for killing two girls in the same Berkshire village less than six months after strangling Yolande.

But why, despite blood from Burgess being found at the scene and his own confessions in jail, did it take police more than four decades to finally bring him to justice?

First blood screening

Yolande had only recently moved to Beenham to work as a home helper at a farm when she went to the village's Six Bells pub on 28 October, 1966.

Yolande had only moved to the village five days before her death

Burgess was also in the pub as the teenager bought a packet of cigarettes before leaving. Officers believe he then followed her before carrying out the attack.

In the struggle, blood from Burgess was left on a number of Yolande's items, including her hair band and comb.

Local police, supported by Scotland Yard detectives, began a large-scale investigation and Britain's first mass voluntary blood screening was held with samples taken from all 200 males aged 16 to 60 in the area.

But when Burgess's supposed sample was analysed it did not match one of the tests - although police now say even if it was an exact match it may have only narrowed him down to one in 100 people with that blood group.

Despite this, he was arrested for the murder. But without the blood match, police were unable to gather enough evidence to charge him.

Detectives now believe Burgess may have got someone else to give a sample on his behalf or it was incorrectly labelled.

'No mistakes'

Less than six months later, in April 1967, the tiny village was rocked again with the double murder of nine-year-old girls Jeanette Wigmore and Jacqueline Williams.

But this time Burgess was caught when blood from one the victims was found on his boot.

He was sentenced to life in prison with a minimum 45-year tariff.

In the late 1960s he made five confessions, with varying stories, about Yolande's murder to different prison officers, but when questioned by detectives he denied these admissions.

A blood stain on Yolande's hair band finally helped to link Burgess to her murder

But despite the admissions and apparent clear links to the Yolande killing no blood samples were ever taken from Burgess during his time in custody.

Then, in September 2010, Thames Valley Police reviewed the case and with advances in DNA techniques finally gathered the evidence to see Burgess convicted of his crime.

Forensic experts obtained a partial DNA profile from the blood samples using a new technique called MiniFiler.

It differs from usual methods as it can obtain information from smaller pieces of DNA - perfect for older cases where samples have degraded.

Tests showed the chances of DNA found on the comb and hair band not being Burgess's were one in a billion.

But when asked whether mistakes were made in the original inquiry, Pete Beirne, head of the Thames Valley major crime review team, answers a defiant "no".

Bank robbery

"On the face of it the investigation was a thorough investigation," he added.

But he did admit a further blood test when Burgess was in jail which proved a match may have helped build the case.

In a separate twist, police are also looking into unsolved murders in the 18-month period when Burgess absconded from open prison between 1996 and 1998.

He was only returned to jail when he was caught for holding up a bank in Hampshire with an imitation firearm and fleeing with almost £2,500.

He was given a further 10 years to his sentence.

Officers are now looking into cold cases from the time to see if Burgess was responsible.

- Published20 July 2012

- Published15 November 2011

- Published16 November 2011