Did the Newbury bypass tree-huggers change anything?

- Published

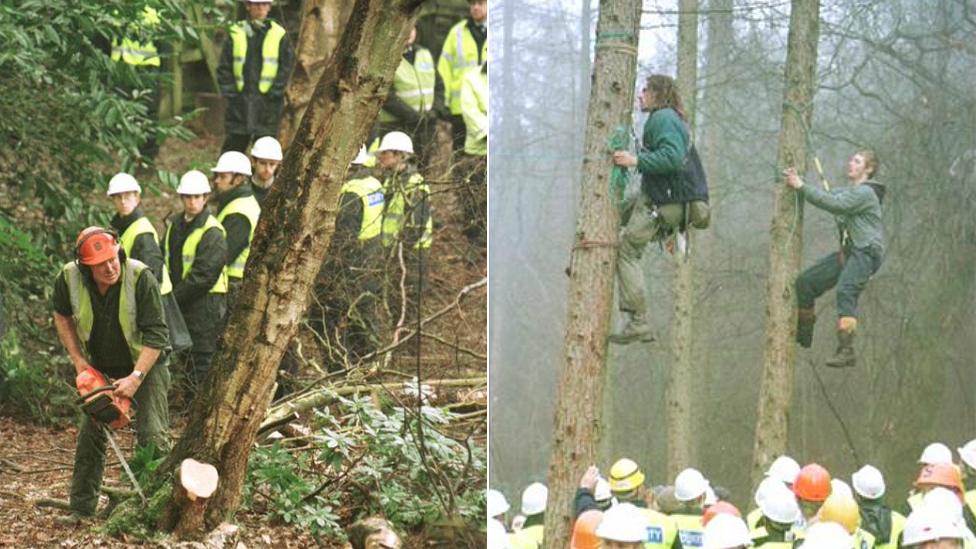

About 800 protesters were arrested during the protest against a bypass being built in Newbury, that led to the felling of 10,000 trees

In January 1996 an army of eco warriors took to the trees in Newbury to try to prevent the construction of the Newbury bypass. The road was eventually built, but 20 years on did the "Battle of Newbury" have a lasting impact?

"In other, less-civilised parts of the world, they might have had the machine guns out."

These were the words of the Under Sheriff of Berkshire, Nicholas Blandy, as he surveyed the Newbury bypass protesters clinging to trees, determined to thwart the bulldozers.

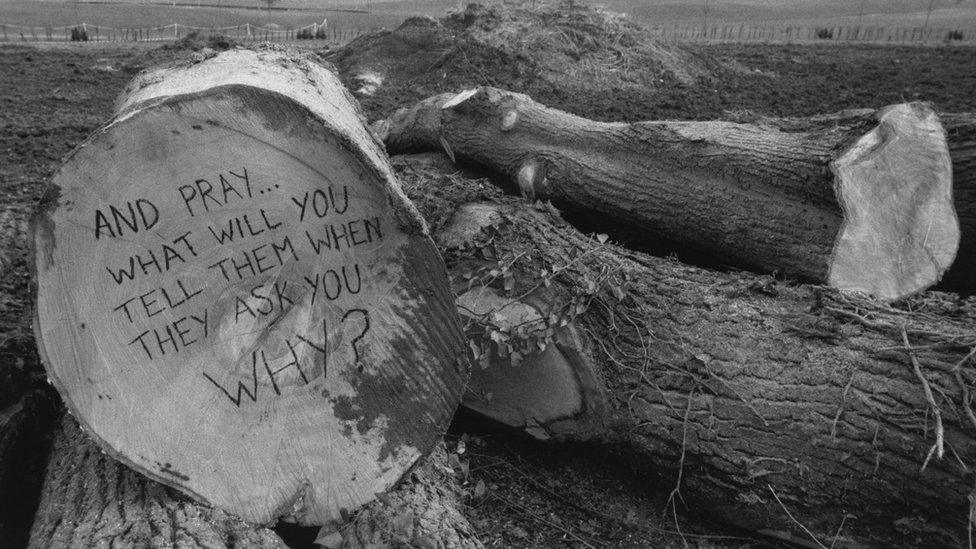

The trees, 10,000 of them, were eventually cut down to make way for the road that would get rid of a notorious bottleneck on the A34.

But this did not happen without a lengthy protest from eco warriors who doggedly chained themselves to trees, dug tunnels and caused a mass disturbance of a kind rarely seen before in England.

Six-hundred security guards were brought in to police the site, at a cost of £25m - one fifth of the total bill for building the road. During the January protests, some 748 people were arrested.

Anti-bypass protests had been going strong in Newbury since the 1980s, but the eventual evictions of the protest camps, tree felling and undergrowth clearance work began on 9 January 1996.

The clash received widespread coverage and protesting figurehead Swampy, external ended up a minor celebrity who appeared on satirical news show Have I Got News For You.

Twenty years on, Mr Blandy said he could now laugh at some of the memories.

Twenty years on from the protests, the law enforcers involved return to the scene

"They had a certain amount of robust contempt for me," he says of the protesters.

"They had a big sound system rigged up in the trees playing Bob Marley's I Shot The Sheriff at loud volumes, which I thought was terribly funny."

Two decades later, Mr Blandy has been reunited with one of the main protestors, Phillip Pritchard, who spent two years campaigning against the bypass.

They both admire an old oak tree that survived the cull, and chat in an amicable way, though they maintain a distance while talking.

Former Under Sheriff of Berkshire, Nicholas Blandy (left) is reunited with bypass protester Phillip Pritchard 20 years on

"I had such extraordinary respect for you because it was just so cold," Mr Blandy told Mr Pritchard.

"It was a bitterly cold winter and I do not understand those who stayed here in the ground or tree houses in the trees.

"Some of the protesters looked so unhealthy because in those conditions you needed [up to] 5,000 calories a day in order to live and you weren't getting it.

"Some people were getting visibly unhealthier as it went on. It was a very hard environment in which to live so to a certain extent I tip my hat off to you."

Nicholas Blandy (left) and Phillip Pritchard were on opposite sides of the bypass argument in 1996

"There was definitely a lot of passion," Mr Pritchard remembers. "[We] were trying to act like an antibody for the Earth - trying to protect nature, to protect what was being destroyed in beautiful places.

"Often people did let themselves become quite ill, [but] there was an amazing network of people from the town.

"People brought food out, people came and had showers and baths in people's houses, that was really amazing although it was hard for people to walk a six-mile round trip just for a bath sometimes."

"At the time we felt quite cross towards the Under Sheriff of Berkshire but I can see you're a person, you were doing your role.

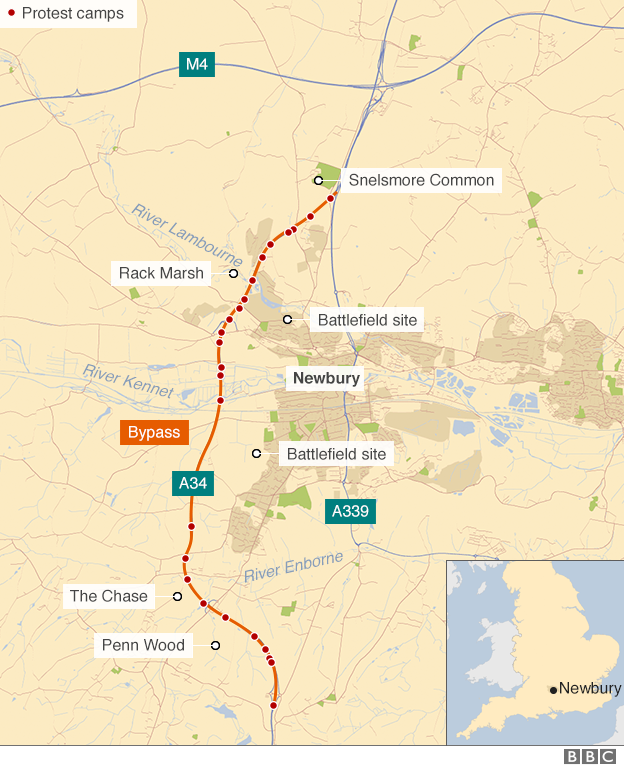

Map showing the protest sites at the Newbury Bypass

"I think it's been a really powerful part of my life and to be here talking to you is an interesting thing."

The intervening 20 years has not mellowed either of them in terms of their views on the situation.

"The years haven't made me in any way regret doing what I did, because I continue to think it's very important that the law is upheld," says Mr Blandy. "In a democratic society governments ultimately have to take decisions that are unpopular to some and they have to be carried out."

Road protests achieved so much media coverage that campaigner Daniel Hooper, known as Swampy at the time, made a guest appearance on the BBC's satirical news show Have I Got News For You

Mr Pritchard points out that the law became a "shifting beast" for the protesters.

"New laws [in 1994] were brought in to make what had been civil matters, such as trespass, into criminal matters - aggravated trespass, which meant that the police came in and arrested people and hundreds of people got criminal records for things that in the 1980s wouldn't have been criminal."

Becca Lush was arrested three times in one week during the 1996 protests

One protester who fell foul of this new law was Becca Lush, who was arrested three times in the first week of the January clash.

"Anyone who was arrested was given bail conditions that prevented them from going anywhere near the protest site, so I was out of action quite quickly certainly at the beginning of the protest," she said.

"But I was able to do all the other millions of jobs that enabled the protest to become prominent.

"It was a national issue, we were all over the national media for months and months, and the whole country knew what the government were doing."

Protestors in 1996 hung out in the trees earmarked for the axe

Despite the campaigners losing, Ms Lush, who now works as a charitable giving manager for an organic cosmetics company, said there was a lot that was gained.

The protest was "absolutely crucial in changing transport policy", she says.

"After Newbury, the Labour government came to power with a manifesto pledge to stop road building and look at the alternatives, which they did do.

"Although there were 600 road schemes proposed initially by the Thatcher government, over the protest years it was whittled down to 150.

"By the time the Labour government came in 1997 the road programme was scrapped completely.

"So by anyone's standard that was an enormously successful campaign - over five years to reduce the multibillion-pound road building programme down to zero."

BBC South Today reporter Paul Clifton covered the bypass protests in 1996

The protesters' legacy - Paul Clifton, BBC South Today

"I spent months reporting the battles at Newbury. One of the biggest tree camps was at Tot Hill. Today, it's a service area with a hotel and a McDonald's.

"Middle Oak became a symbol of the campaign: a solitary tree in the middle of cleared woodland was allowed to remain standing, a minor concession to the protesters.

"Driving past today you can barely notice it, tucked into a bend of the slip road between the A34 and the A4. Around it, some of the 200,000 new trees planted to replace the 10,000 cut down are starting to mature.

The landscape before and after the Newbury bypass was built

"The protesters lost the battle. But perhaps they won the war.

"There is no doubt the tree climbers swayed public opinion and, later, political policy changed too. It virtually halted the construction of major new roads for a generation.

"In the 20 years since the bypass was built, only two significant new roads have been created in this part of England: the Hindhead tunnel on the A3, and the Weymouth Relief Road.

"As Newbury was being built, a tunnel past Stonehenge in Wiltshire and a bypass for Arundel in West Sussex were being talked about. Twenty years later, they are still only being talked about."

And with the memories of 20 years ago still fresh in the minds of both the protesters and law enforcers, the legacy of the trees that were felled also lives on - albeit it not in Newbury.

Mr Pritchard says: "We collected tree seedlings that had sprouted where the trees had been cut down, and planted them in other parts of the country.

"Some of them are now way taller than me."

A final message from one of the protesters as 10,000 trees are felled to make way for the bypass

- Published9 January 2016

- Published9 January 2016