Amelia Dyer: The Victorian nurse who strangled babies

- Published

Amelia Dyer offered young, unmarried mothers a solution to their "problem"

Amelia Dyer is believed to have murdered hundreds of babies during the 19th Century. Her crimes led to one of the most sensational trials of the period and shone a spotlight on the Victorian practice of "baby farming". How did a seemingly respectable woman stoop to such cruelty?

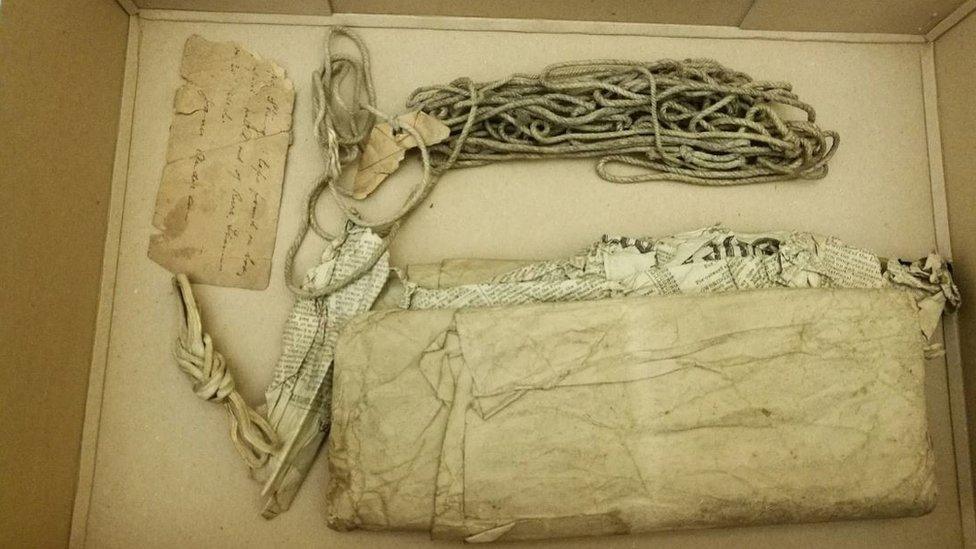

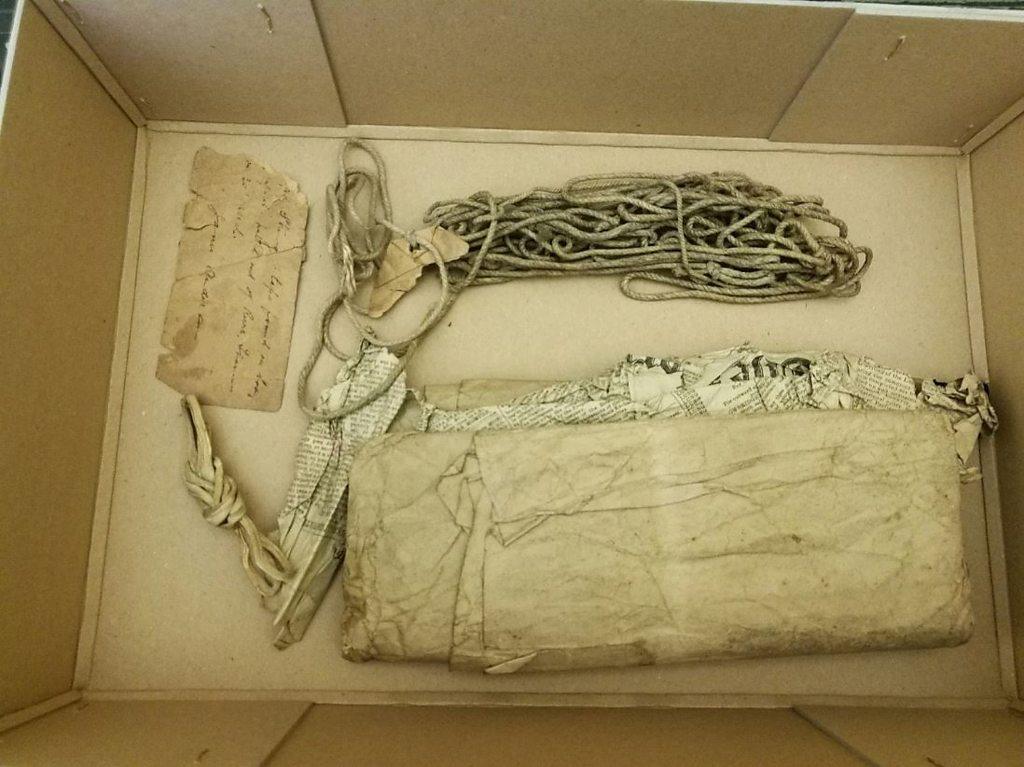

On 30 March 1896, a parcel weighted down with a brick was fished out of the River Thames in Reading.

Inside, swaddled in layers of linen, newspaper and brown paper, was the partially decomposed body of baby Helena Fry. White tape had been wound around her neck, with a knot under the left ear.

It was a gruesome discovery, but one which would lead detectives to unravel the crimes of one of the 19th Century's most notorious child killers.

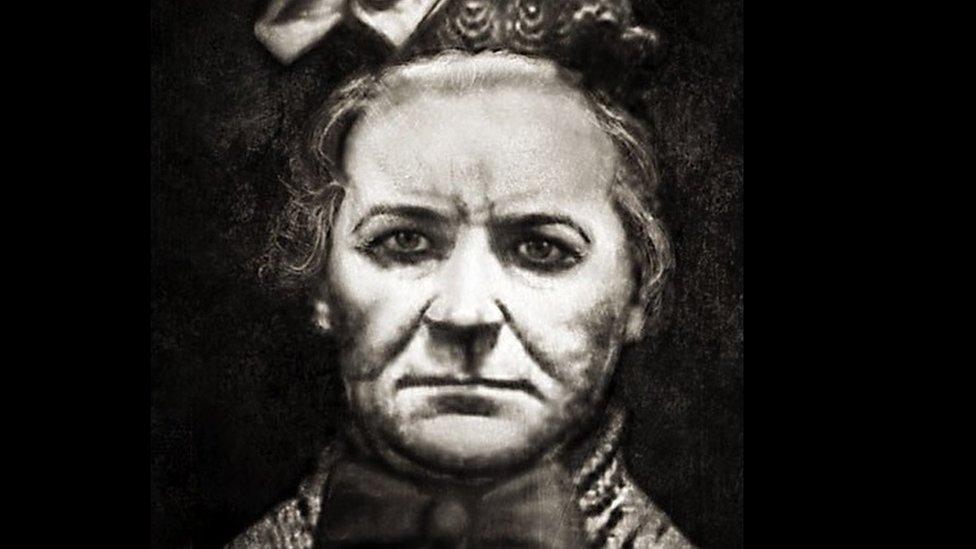

Born in 1837 to a shoemaker in a small village in Bristol, Dyer had endured a tough childhood in which she was the main carer for her mentally ill mother.

As an adult, she became a nurse. But, rather than use her skills to care for people, she embarked on a career doing the exact opposite.

"Baby farming" was a practice common in Victorian England, fuelled by desperate single mothers whose perceived immorality meant they were barred from the workhouse.

Their options were limited, namely to prostitute oneself, starve or, instead, quietly "get rid" of their baby. Baby farmers would offer to take the children off their hands and offer it an alternative future - albeit, not necessarily a happy one.

It was into this world that Dyer stepped in.

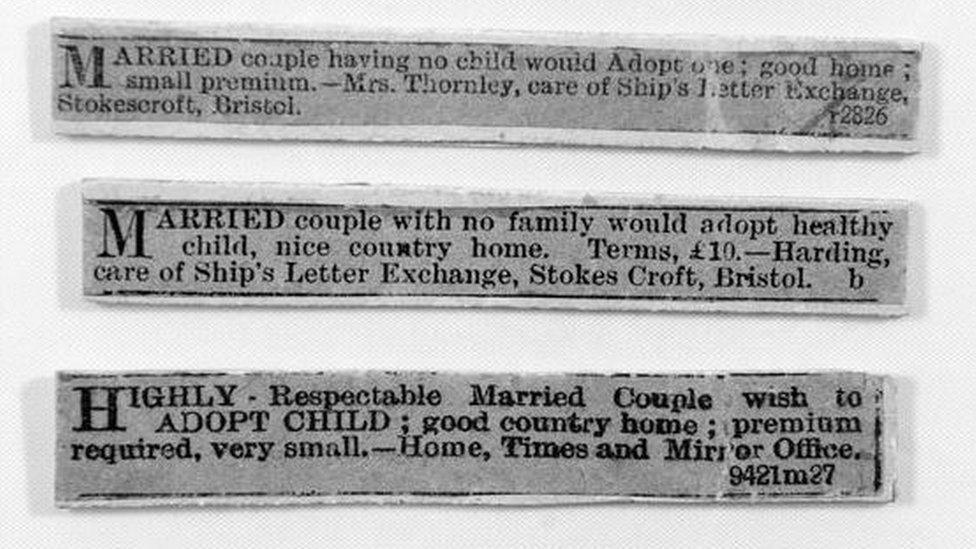

Dyer advertised her services in newspapers, describing herself as "highly respectable"

Recently widowed and with a daughter to support, she learned of the practice from a colleague. In 1869 she began advertising in local papers - "Married couple with no family would adopt healthy child, nice country home. Terms - £10."

But instead of providing a safe and loving home, she would instead take the child for a fee and murder them - either by starving them, drugging them with an opiate-laced cordial known as Mother's Friend, or by strangulation.

"At that time, baby farming was widespread," said Dr Charlotte Beyer, a lecturer at the University of Gloucester.

"Countless babies and children suffered and died as a result of this practice and in many cases, 'fostering' meant killing - slowly or quickly."

Dyer began killing her victims by overdosing them with a cordial known as Mother's Friend

The social conditions within Victorian England appear to have enabled Dyer to get away with conducting her grim business for almost 30 years.

With high infant mortality rates being a sad fact of Victorian life, early deaths often escaped the notice of the authorities.

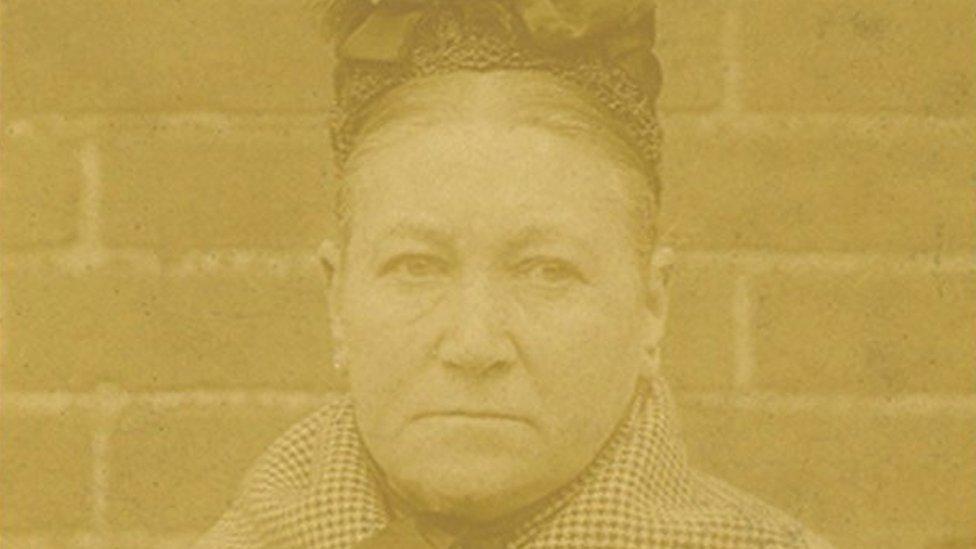

Dyer travelled from her homes in Bristol and Reading to as far afield as Liverpool and Plymouth, charging between £10 and £80 - equivalent to about £1,000 and £8,000 today - for her services.

Most babies left in her care were murdered within days, or in some cases within hours, said PC Colin Boyes, curator of the Thames Valley Police museum, which houses an exhibition about her crimes.

Angela Buckley, author of Amelia Dyer and the Baby Farm Murders, said her victims' parents would not have known she planned to kill their children.

"They believed that they were sending their child to a happy home," she said.

Her luck ran out briefly in 1879 when doctors became sceptical over the number of deaths certified in her care and she was sentenced to six months' hard labour for neglect.

Dyer turned to baby farming after the death of her husband in 1869

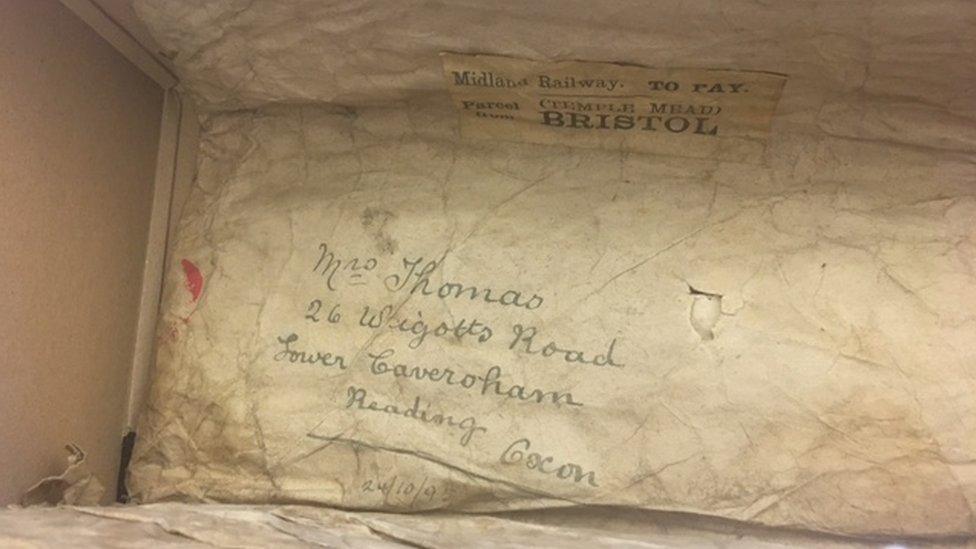

Packaging found with the body of Helena Fry contained clues which led to Dyer's capture

But it was not enough to deter her from continuing her grisly business. Upon her release, Dyer changed her modus operandi.

After a brief spell lodging in Cardiff, she relocated to Reading in 1895 and, realising the folly of involving doctors to issue death certificates, began disposing of the bodies herself by throwing them in the River Thames.

But it was this which led to her eventual downfall.

When Helena Fry's body was fished from the water, Det Con James Beattie Anderson examined the packaging - now on display at the police museum - and spotted a clue.

The packaging bore a Midland Railway stamp dated 24 October 1895 and was marked Bristol Temple Meads.

More importantly, he could make out the smudged name and address of a Mrs Thomas of 26 Piggott's Road, Caversham - Dyer's married name and former address.

Dyer turned to disposing the bodies of infants herself to avoid suspicious doctors

The search for a murderer took him to the town, where neighbours told him she had moved to Kensington Road in Reading.

On arrival, the detective found piles of baby clothing and numerous receipts from advertisements in various newspapers from across the country.

White edging tape identical to that discovered around Fry's neck was also uncovered and on 3 April 1896 - four days after her body was discovered - Dyer was arrested and charged with having feloniously killed a child.

Six more babies were found after the Thames and Kennett were dredged, all with the same tape around their necks.

One parcel spotted near Clappers Pond revealed a particularly gruesome discovery for Det Con Anderson.

"Taking it straight to the mortuary, it was confirmed that the corpse was that of a female child, aged about 12 months," explained Ms Buckley.

"It was in more of an advanced state of decomposition than any other of the bodies recovered - so much so that that when the parcel was opened, the body and head fell to pieces."

The evidence used to convict Dyer was later found in the loft a house belonging to Det Con Anderson's relative

On 22 May 1896, she appeared at the Old Bailey for trial. The only defence and explanation the 57-year-old offered was insanity - having previously been committed to asylums in Bristol.

But prosecutors argued her exhibitions of mental instability were merely a ploy to avoid suspicion.

The true scale of her crimes is hard to estimate. At her most active, eyewitnesses reported seeing as many as six babies a day being taken into her home.

"Given that Dyer practised as a baby farmer for some 30 years, it is likely that she was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of children," said Ms Buckley.

"She had only spent nine months in Caversham but Reading police found evidence that she had cared for at least 15 babies at her home during this time.

"The idea of women killing anyone was very shocking, but the fact that she killed babies was beyond the pale."

Each of Dyer's victims were strangled with white tape, which as she later told the police "was how you could tell it was one of mine"

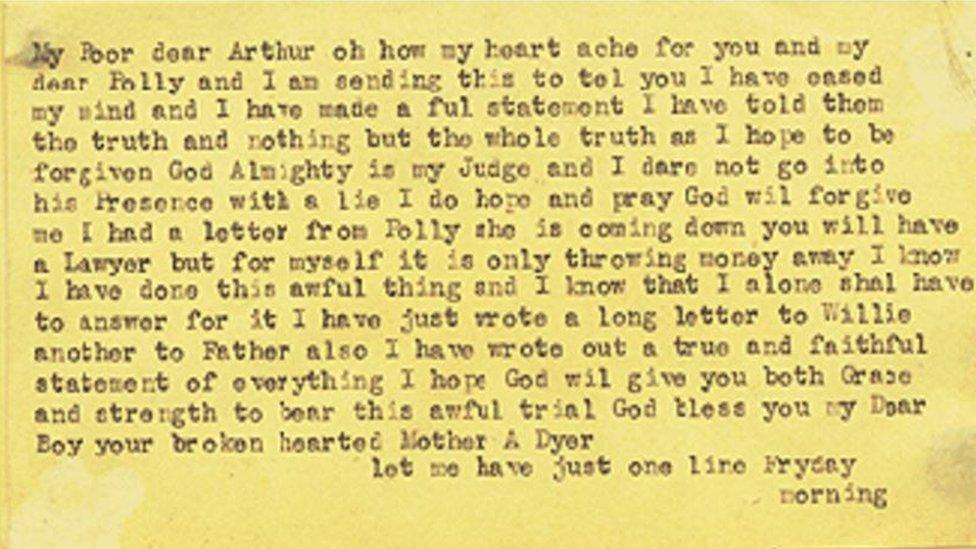

Dyer confessed to the crimes shortly before she was hanged

In addition to gaining justice for those she killed, the case against Dyer also highlighted a dark underworld in which mothers were giving their children away.

"The trial brought to light the otherwise repressed but widespread practice of baby farming, and revealed the horrors and inhumanity of this trade," Dr Beyer said.

"It took the Dyer case for the law to be pursued more effectively and rigorously at a national and local level, and for the then newly-established NSPCC to begin to become more influential."

Dyer was hanged at Newgate Prison on Wednesday, 10 June 1896, having eventually confessed to her crimes.

Horrified residents in Reading carved wooden crosses in the handrail of Clappers footbridge - a memorial to the innocent victims of a prolific baby killer who took advantage of society's intolerance to exploit its most desperate members.

- Published17 March 2017

- Published7 March 2017