Could Birmingham's library cuts harm the city?

- Published

Opening hours and various services at the library are to be cut under council cost-saving plans

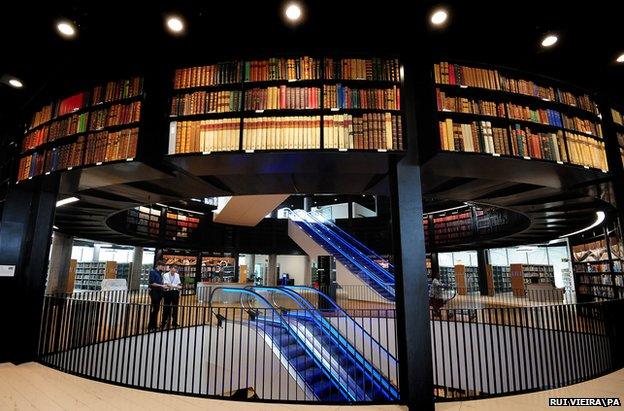

It was opened by a Nobel Peace Prize winner, has been listed for prestigious awards and described as a cultural icon. Now, just 18 months after lending its first book, the Library of Birmingham is to lose almost 100 staff and see its opening hours slashed in half. But what does it mean for the city?

With its amphitheatre, performance areas and business suites, the £189m building was touted as a "reinvention" of the traditional library.

It drew 2.7 million visitors, loaned out 316,000 books, DVDs and CDs, and saw membership rise to over 250,000 people in its first year.

But its £10m annual running costs, coupled with a £1m monthly debt bill to repay construction fees, has, the city council said, left it with no choice but to make cuts.

Events and exhibitions, outreach programmes and some archive services face being axed under the new financial regime, while opening hours will drop from 73 to 40 per week.

Campaigners say reducing services at the library would create an "empty shell" and "embarrass the city". But are they right?

Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai opened the library in front of large crowds

Reduced opening hours will mean less chance to use the library for study, campaigners argue

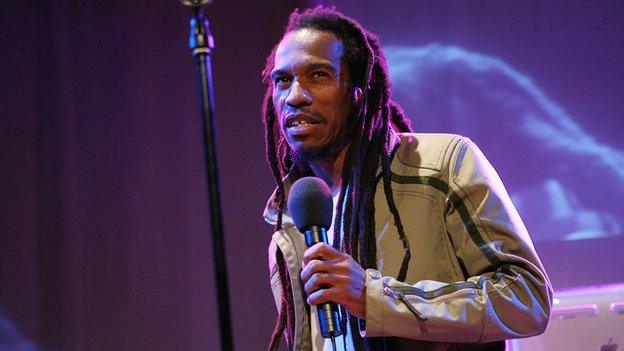

Poet Benjamin Zephaniah, who welcomed the library's opening, released a statement ahead of the final cuts announcement.

In it, he said he feared cuts to the library could damage Birmingham's image.

"I was telling my friends all over the world that Birmingham was the place to be," he said, "but in a very short time I have gone from pride to fear".

"If Birmingham is to take its place as a great world city it should keep investing in this and other libraries, and by doing so it will be investing in its people and its future."

The library has been credited with drawing swathes of visitors to Birmingham since it opened, coinciding with the city's appearance in a list of the world's ten must-visit cities, external.

University of Birmingham marketing professor Isabelle Szmigin said she felt the building had been a "critical aspect" of its rise in the tourist guides.

"It's architecturally significant in a city that hasn't always been that great on that," she said.

The library's raised terraces, which offer views of the city, are a draw for tourists

Prof Szmigin, who described the building as the city's "show-stopper", said news of the cuts to a much-celebrated building "was a bit of a downer".

"The library should be the city's flagship place in Birmingham," she said.

"You wouldn't find the big premier brands closing their flagship stores."

"They signify something to the outside world."

As well as reputational damage, there are fears limited access to exhibition and performance spaces could hamper the city's arts scene.

Photographer Daniel Meadows, who donated his life's work to the library's archive, said he had done so on the premise "it could be enjoyed, shared and researched by library visitors in perpetuity".

He described its photographic collection of about 3.5 million images as "a great wonder and of huge international significance".

The library's architecture saw it shortlisted for the prestigious RIBA award

Although proposed cuts to the photography archives team were scaled back in response to public concerns, the issue of reduced library access remains a concern.

Sara Beadle, programmes director for literature development agency Writing West Midlands, said it would be affected by reduced opening times.

She said the organisation, which stages literary and creative writing-related activities at the library, faced a reduction in the availability of "already sparse" arts spaces in the city.

Fewer evening hours would lessen access to events and activities, she said.

"If the reduction in hours and staff means that we can't get in there, or can't afford to use it if they are forced to raise their prices, it will have an impact on our work," she said.

Benjamin Zephaniah said his "pride" in the library had been replaced by fear

Questions also remain over how the council found itself struggling to fund the library so soon after it opened.

Councillor Penny Holbrook, cabinet member for skills, learning and culture, said the roots of the problem began when the building was commissioned in 2007 - a year before the financial crisis took hold.

At the time, she said, no-one could have foreseen the scale of budget cuts which would face local authorities years later.

"If you could have predicted the level of cuts and were making the decision today you might do things differently," she said.

But can anything be done to balance the books?

Prof Szmigin wondered whether the council could use the building in more imaginative ways to raise cash.

"It's a significant space that could be used for many things," she said.

"When you're up an alley with nowhere to go you have got to think 'what can we do?'

"Turning around and saying 'it's not going to work for us' would be a terrible mistake for me."

- Published10 February 2015

- Published10 December 2014

- Published7 November 2014

- Published16 September 2014

- Published26 February 2013

- Published9 December 2013